|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

Story by Bill Lambrecht Photographs by Kenneth Lambert

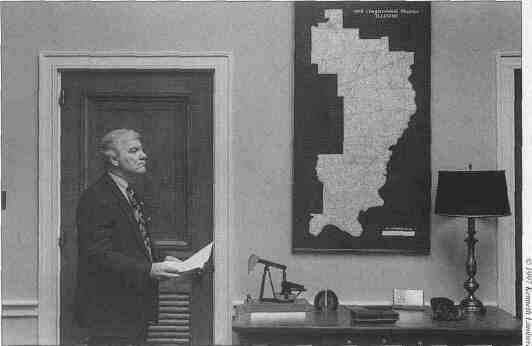

See this baby? This is my bed," says U.S. Rep. Glenn Poshard. He has just yanked open a closet in his Washington, D.C., office and now he's pointing to a heap of blue plastic next to a stack of yellow blankets. "That thing blows up and makes a big old air mattress. I sleep right there on the floor," he says, pointing toward the middle of his office at a swath of red carpet where feet have just trod.

Poshard, a Democrat from Marion in deep southern Illinois, and a candidate for governor, is not the first member of Congress to bunk in his office. Nor is he alone in displaying only art from back home in his reception area: diploma-sized drawings of an old slave house in New Equality; the territory's first bank in Shawneetown; the Garden of the Gods in the Shawnee National Forest; and, the first thing a visitor sees, a prairie chicken.

But in a Congress short on characters and long on a new vanilla blend of blow-dried homogeneity, Poshard stands out. It's more than his mustache or the aw-shucks demeanor that belies his Ph.D. Few members in Congress from any region fit their districts so perfectly. And not many represent theirs so unswervingly.

Poshard, in his fifth term, was first elected to Congress in 1988. He now represents the 19th District, which encompasses all or parts of 27 counties in central and southeastern Illinois.

In his values and his votes, the moderate Poshard he's anti-abortion and critical of the Clean Air Act has exhibited a way-down-in-Illinois approach to his nine years in Con- gress. He has stuck with matters of economic concern to his rural and blue-collar district, such as health care and coal mining, and left the global issues to colleagues.

Soon after he hit town, he began organizing colleagues into spiritual gatherings like a southern Illinois circuit preacher. But he has done battle with the Christian Coalition, taking to the House floor to chastise the Christian Right for insensitivity to social programs and budgeting for the poor.

Poshard, who turned 53 last month, has that unbridled streak of populism that has run through southern Illinois politics since the rural depressions of the late 1800s. Many southern Illinoisans were drawn then to the Democratic Party and to William Jennings Bryan, who was born in Salem, 111., and looked contemptuously at big-city politics and the clout of the well-heeled.

Poshard, too, is an accomplished orator with a rural upbringing and a politician who relishes the independence he gets in declining checks from political action committees. His refusal since 1988 to be on the receiving end of PAC largesse is a defining feature of his political identity. But that hardheaded populism will be put to the test next year if Poshard wins his primary and seeks the wherewithal to fuel a full-blown, eight-month statewide campaign.

He's just as stubborn when it comes to the U.S. Constitution: Poshard, an army veteran, hasn't been afraid to make himself unwelcome at Friday night VFW gatherings by voting against the amendment that would prohibit flag-burning.

Whether in Washington or in Illinois, the old-fashioned brand of politics Poshard practices has often landed him in a clash of cultures. The pro-choice abortion placards that have greeted him campaigning in Chicago are scarce down in his home turf. Most state legislators south of Springfield call themselves pro-life, reflecting the often conservative, even fundamentalist views in the bottom tier of the state.

Poshard's anti-abortion stance may be too deeply rooted in his Baptist faith for him to consider moderating it, as have other Democrats in the region with their eyes on higher office: Illinois' U.S. Sen. Richard Durbin, who once represented the congressional district encompassing Springfield, and House Minority Leader Richard A. Gephardt of Missouri, to name two.

But Poshard departed from conviction in altering his opposition to another key issue that reflected a strong sentiment in his district: his opposition to the ban on assault

Illinois Issues November 1997 / 27

Glenn

Poshard

Glenn

Poshard

weapons. Guns, mostly used for deer hunting, are deeply ingrained in southern Illinois culture. Next time it comes up for a vote in the House, though, Poshard has resolved to take this advice from former U.S. Sen. Paul Simon: "Glenn," Simon told him earlier this year, "you need to rethink your position on guns."

To understand Poshard on the floor of the U.S. House or on the floor of his Washington office, for that matter it helps to know where he came from.

We'll let Poshard tell us why, with a salary that soon will rise to over $136,000, he blows up an air mattress at night. "I had an apartment for eight years, just north of Old Town on Duke Street," he says, pointing south across the Potomac River to Alexandria. "I would go home at 12 or 12:30 at night and I could never find a parking place; sometimes I would have to park half an hour away. I'd have to be in here at 6 in the morning. So gosh, I'm paying a thousand dollars a month for apartment and electricity and all, and I'm sleeping there for two or three nights a week for three or four hours," he says.

"I just got sick of it all."

Frugality runs deep in many who were raised with little in rural settings. Poshard is descended from French immigrants who settled Illinois as farmers. (He pronounces it puhSHARD. Relatives in central Illinois say PO-shard.) Lessons Glenn learned early in life in White County, near the Indiana and Kentucky borders, foretold a chief aim when he made it to Washington many years later: reducing the federal deficit.

Poshard tells another story: "When I was growing up, every Friday night, my dad [Louis Ezra Poshard] put the check on one side of the table, the bills on one side of the table." Poshard drops his left hand, palm down, and then the right. "We figured out what we had, what we had to pay out. And the difference was what we went into town with the next day and traded."

He has run his congressional office the same way, refusing the congressional perk of free mailing and saving well over $1 million by pennypinching, a survey showed. He has been a dependable budget hawk, casting his lot with a coalition of moderate "Blue Dog" Democrats who often aligned themselves with Republicans in pushing spending cuts.

The Concord Coalition, which is dedicated to budget-balancing, ranked Poshard second among Illinoisans in the House last year, behind Republican Rep. John Porter, for his votes to cut government spending and reduce the deficit. They called their report "Tough Choices: Who Made Them And Who Didn't."

Poshard's choices many times have seemed parochial: He was one of just 12 Democrats who joined 222 Republicans in 1995 to trim $4 billion from foreign aid. Yet he has been anything

28 / November 1997 Illinois Issues

but shy about pushing spending projects for his district from his position on the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.

He has been aggressive in supporting subsidies and tax breaks that total more than $500 million yearly for corn-made ethanol, which indirectly helps his farmer constituents. A primary beneficiary of the subsidies is the giant corn-processing company Archer Daniels Midland, headquartered in Decatur in the northeast corner of Poshard's district. Outside of the Midwest, ethanol subsidies are viewed as one of the most enduring taxpayer rip-offs in America.

And Poshard is not too parsimonious to propose spending hundreds of thousands of dollars to commemorate the underground railroad sites from the crusade to usher slaves to freedom.

Illinoisans in Congress routinely take a less sympathetic view toward environmental legislation than counterparts from regions with coastlines and more of their remaining natural resources to protect. Poshard is no exception. Often he has viewed his district as a victim in the wave of environmental lawmaking of the past decade.

He voted against the Clean Air amendments of 1990, changes that hastened the demise of the southern Illinois coal industry by forcing utilities to look in other states for coal with lower sulfur content. Likewise, he opposes the new regulations ordered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1997 to cut allowable levels of ozone pollution by one-third and begin regulating tinier particles of soot and other airborne impurities.

It may seem odd for a southern Illinoisan to be aligned with oil companies. But Poshard has been a co-chair of the Congressional Oil and Gas Forum, fighting along with Alaskans and Louisianans for limiting regulation on oil exploration. Why? Illinois, in addition to being second only to Iowa in corn production and leading the nation in recoverable coal reserves, is the 14th largest producer of oil.

In 1996, Poshard was among 95 members of Congress who signed a letter to President Bill Clinton protesting what they termed "the serious and detrimental impact of unwarranted federal regulations on domestic oil and natural gas exploration." The letter opposed new rules for conducting natural resource damage assessments of oil drilling as well as expanding the Toxic Release Inventory, a federal law that forces industries to disclose the pollution they cause.

Would Poshard's seemingly anti- green outlook as a congressman conflict with his responsibility as governor to look out for asthma sufferers in Chicago and the well-being of his entire state? He doesn't think so, noting Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley's opposition to the newest changes in air-pollution rules.

"I suppose my district does weigh in pretty heavily," he said, referring to some of his environmental votes. "I've always felt you have to maintain an appropriate balance between environmental consideration and jobs. I voted against the Clean Air Act. But I thought it should be a national policy that every state had some responsibility for cleaning up the air instead of just laying that heavy burden on seven or eight high-sulfur [coal] states."

| For

More Information

Illinois Issues has profiled two other Democratic candidates for governor. For a look at John Schmidt, see June, page 22. To read about Jim Burns, see July/ August, page 22. Later, we will profile Democrat Roland Burns and George Ryan, the Republican candidate. All of the profiles of candidates! for the state's highest office also will be available through the magazine's home page. Our web site address is: www.uis.edu/~blee/ ii.html. Just look up the site and follow our links. |

By the same token, Poshard will be remembered for his efforts to preserve the Shawnee National Forest, which covers portions of 10 counties located in the wedge between the Ohio and the Mississippi rivers. In 1990, he spearheaded an effort to include tracts of the Shawnee in the nation's storehouse of preserved national wilderness areas. Poshard says that others before him had ducked the issue due to the sway of property-rights enthusiasts in southern Illinois.

But saws never will roar in Shawnee's newly preserved Bald Knob Wilderness, Bay Creek, Burden Falls and Panther Den because of rules forbidding mechanized activity of any sort. In the Garden of the Gods that precious hideaway of unusual rock formations featured on Poshard's wall developers can't even ride their bicycles.

Before many politicians make career decisions, they head to the proverbial mountaintop to reflect. For Poshard, that journey is real: Twice yearly sometimes, he cloisters himself in a Trappist monastery in the hills of Kentucky. "I just zonk myself away for six or seven days and try to get things in perspective. Because this is an easy job for things to get out of perspective."

Poshard believes in the power of the spiritual to temper the hubbub of Washington. He has been a pioneer in persuading others of the wisdom of that course. That quest began soon after he arrived in Washington. By chance, he was seated at a freshman orientation with the Rev. Doug Tanner, husband of Kathy Gille, a top aide to House Minority Whip David Bonior, a Michigan Democrat. They talked about Capitol Hill's shortage of outlets for like-minded members to gather for spiritual reflection.

Out of that conversation came a devotion group that met in one of Poshard's earlier offices in the Long- worth Building on Wednesday mornings. "We just thought that it was something a lot of people would enjoy getting together for an hour and just saying, 'Okay, where are you, what's pulling you today away from the basics?'"

Those Wednesday gatherings have anchored Poshard's weeks in Washington for nine years. They sprouted

Illinois Issues November 1997 / 29

other such groups, which have become linked together in a nonprofit organization called Faith in Politics Inc. As a board member, Poshard has watched the organization's activities expand from chat sessions to the practice of good works, among them helping to rebuild churches burned in hate crimes.

Sensitivity to the suffering of others tempers Poshard's parochialism. Politics seems part of his motive for moderating his tolerance of owning assault weapons. But he attributes his final decision to shift to what he saw on the crack-driven street corners and in hospital emergency wards when touring Chicago with AfricanAmerican leaders.

Likewise, Poshard's desire to assist troubled coal miners in his district triumphed over his fiscal conservatism. He fought successfully against a drive by former Missouri Rep. Mel Hancock and other Republicans to cripple the law that governs miners' retirement benefits. "There is no sense in rubbing out this [law] just because certain people have the power to do it," he argued.

In 1995, Poshard returned from a trip to Bosnia with an altered view of the U.S. role in that troubled region. Before he left, he was skeptical of sending in U.S. troops. On their trip, Poshard and 27 other members of Congress witnessed scenes he described as gut-wrenching, among them vivid descriptions of children dying in mortar fire.

"The vital interest here is American leadership," he proclaimed on his return.

And Poshard's belief in the Bill of Rights gets put to a test whenever . sponsors insist on a roll call on the proposal to add a Constitutional amendment to ban flag-burning. Poshard, a veteran of the Army 1 st Calvary Division who was stationed in Korea in the 1960s, gets pummeled in his district each time he votes no.

He calls those votes the most difficult in his years in Washington. "I just think that the precious right and responsibility that any citizen has to criticize their government should not be fettered. It's the difference in government monopolizing our lives and keeping the government at bay," he explains.

Poshard, who earned his doctorate in higher education administration from Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, has taught high school history and government. He began his political career as director of the Southern Illinois Regional Education Service Center and as director of the Area Service Center for Educators of the Gifted. In August 1984, he was appointed to the state Senate. He was elected to the seat that November and re-elected in 1986. He went to Congress two years later. His wife, Jo, is a public school teacher. He has two adult children, Dennis and Kris.

Poshard wants to lead Illinois, but he has no aspirations to rise to the heights in Congress of modern Illinois bred luminaries like Everett Dirksen, Paul Douglas or Bob Michel. He has operated in Washington as a citizen-legislator who term-limited himself to a decade in Washington. During that time, he worked quietly and, by most accounts effectively, on matters that concerned his district.

So quiet were his efforts that the venerable Washington weekly, Roll Call, named him to the House Obscure Caucus. He has been the workhorse, always on time and trudging ahead, not the showhorse. In style, he's the antithesis of his predecessor, the flamboyant Rep. Kenneth Gray of West Frankfort, the auctioneer/magician- turned-lawmaker, who campaigned for office in a fur coat flanked by gospel singers.

But Poshard can turn on a crowd like Gray could, a requisite for success among southern Illinois politicians

30 / November 1997 Illinois Issues

from the Salem-born William Jennings Bryan to Republican state legislator C.L. McCormick of Vienna, known for many years in Springfield for his rhapsodic mosquito abatement speech in which Little Egypt's robust mosquitos carted off cattle.

Poshard may well be a bridge between the old era of southern Illinois politicians and the new. His refusal of PAC contributions represents a departure from the hand-out era of Paul Powell, the secretary of state from Vienna whose shoeboxes were found bulging with cash after he died in 1970.

John Jackson, a political scientist and administrator at Southern Illinois University, believes that Poshard has blended some of the old populism of the region, "the us against them, the little guys against big guys," with the reformist instincts exemplified by former U.S. Sen. Paul Simon.

In Washington, not long before he settled plans to leave Congress, Poshard saw that some of those reform efforts would be futile. "I believed at the beginning of my tenure here that the Congress would enact meaningful campaign finance reform," he declared two years ago. "I no longer believe we will accomplish that task."

Poshard enters a crowded field in his bid for governor. As it stands now, the Democratic ticket includes Chicagoan John Schmidt, a former U.S. Justice Department official, former state Attorney General Roland Burris and former U.S. Attorney Jim Burns of Evanston. (Secretary of State George Ryan is running on the GOP ticket.)

Poshard's

ratings in Congress

|

Poshard's downstate base could be his greatest asset and his greatest weakness. Though Burns grew up in McLeansboro and Burris grew up in Centralia, Poshard is the only announced candidate for governor who lives south of Chicago. That has given him the edge with some downstate party officials frustrated by the GOP's two-decades-long control of the state's highest office. Though the Democratic State Central Committee has yet to endorse candidates, 87 of the state's Democratic county chairmen threw their support to Poshard last summer. And a number of downstate elected officials are in his camp, including state Sen. Penny Severns of Decatur, who ran for lieutenant governor four years ago.

But Poshard also has made inroads with top Chicago-area Democratic politicians, including U.S. Rep. William Lipinski, who represents that city's Southwest Side, Edmund Kelly, 47th Democratic Ward committeeman, and former state Senate President Phil Rock of Oak Park.

He'll need that help in building name recognition and support in the Chicago metropolitan area because his southern Illinois home base is sparsely populated. Cook County accounts for almost two-thirds of the state's Democratic vote. And it's an expensive media market, presenting a potential handicap to a candidate who has sworn off PAC money.

After a decade as a backbencher in Washington, Poshard could easily have retired as a college professor, or maybe a university president, with an income gilded by pensions from Congress and the Illinois General Assembly. Yet here he is, aiming to grab the reins of a state of 12 million people. Did the deeply religious Poshard see a vision, like Saul on the Road to Damascus, that jarred him onto a new course in life?

No. Poshard sees his decision to run for governor as simply continuing what he does best: quietly mastering intricate issues the federal budget, health care, farm policy.

"I pay attention to basics," Poshard says. "I show up for work every day. I don't miss [hearings in] committees. I don't miss votes. I work on what I think you were sent here to work on, which is the guts of legislation in committees. I'm not on the floor all the time speaking. I think you ought to go there when you feel strongly about something."

What Poshard has felt strongly about in Washington is the everyday interests of southern Illinoisans who look at life in a moderate, modest way. His goal is to one day assert from the second floor of the Statehouse in Springfield what he says from his office in the Rayburn Building in Washington.

"I didn't come here to be an authority on everything in the world. I came here to help my people."

Bill Lambrecht is a national political writer in Washington, D. C.,for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. A longtime Illinoisan who has covered the Statehouse, he wrote about energy policy for Illinois Issues' premier edition in January 1975. His articles on utility regulation in 1981 won the magazine's first national award, given by The Washington Monthly.

Illinois Issues November 1997 / 31