|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Janice Tauer Wass Material culture is the physical evidence of human experience. It includes the vast numbers of objects that people use in every aspect of their liveseverything from buttons, tools, ceramics, and furniture to houses, roads, and cities. The objects vary in cultures separated by geography, time, and belief systems. The material culture of the South Sea Islanders will vary widely from the Alaskan Eskimos, nineteenth-century Illinois farmer from the twentieth-century Illinois farmer. Even people sharing the same time and environment, such as the Kaskaskia Indians and French colonists living as neighbors in eighteenth-century Illinois, will have their own material culture. By studying material culture we can learn much about human behavior, creativity, and the impact of economic, environmental, and technological forces on the common man. Material culture study is an interdisciplinary field that involves anthropologists, archaeologists, sociologists, psychologists, geographers, museologists, historians, and art historians. Through their combined efforts, research can illuminate the complicated interactions between people and things. Material culture study seeks the answers to many questions including why things were made, why they took the forms they did, and what social, functional, and artistic needs they served. Material culture study can offer insights into the lives of people who have left little or no other records. Historians are learning from archaeologists how to reconstruct the patterns of life in the past. Methods for studying material culture are exploratory and experimental. No scholarly doctrines are yet established, although several scholars have offered research models. Researchers agree that study needs to build on a rigorous and systematic examination of the evidence that proceeds from discovery, identification, and classification of material culture to the thoughtful analysis and interpretation of these artifacts in cultural context.

2

DISCOVERY

In studying the material culture of the past, historians look to museum collections and archaeological digs for most of their evidence. Researchers must carefully consider the limitations of those artifact collections. Museum collections are largely composed of objects that have been selected for preservation due to their artistry or history. They may not be representative or typical of objects used in a large cultural context. Objects usually end up in a museum because they are the "best" objects that have been made or because they were used for special occasions. On the other hand, archaeological artifacts are often the broken remains of objectsthe trash that was dumped or buried. Only by examining material culture from many sources and comparing artifacts to written and pictorial records can historians attempt to fully understand material culture.

IDENTIFICATION

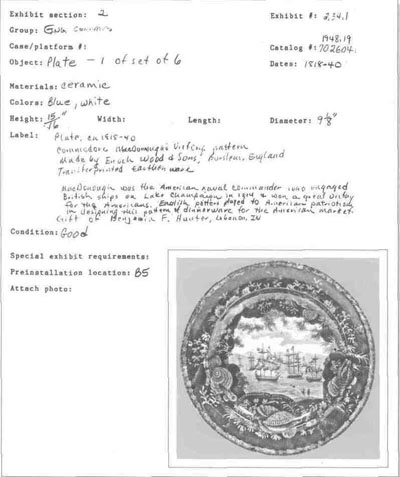

Museums can provide examples of procedures in identifying objects. Since the 1920s the Illinois State Museum has been collecting historical objects made or used in Illinois. When a curator considers adding an object to the collection, he or she gathers as much information as possible from the sourceusually a donor who is offering a family heirloom. The curator, the donor questions to determine who made or purchased the object, when and where they lived at the time, where they bought how much they paid, etc. Photographs of the object in use, or receipts, are also solicited for the documentation files at the museum. The curator then researches the object to determine if there is evidence that conflicts with the information provided. It is possible for information that has been passed down through several generations to lose veracity, as the oral tradition may become confused. Research can also add identifying information that the source may not know, such as the maker and date of manufacture.

CLASSIFICATION

The curator then completes a catalog record for the object. Identifying information is added to the donor information; the object is classified by function, style, materials, and techniques of manufacture; and the condition of the artifact is evaluated. Often the identification and cataloging process requires research using books about types of objects, such as kitchen tools, paper-weights, clocks, or American porcelain. In an attempt to standardize terminology, many museums have agreed to use Nomenclature, a classified lexicon of object names based on function. For example, "chest of drawers" is used instead of "bureau." Curators also can use the Art and Archaeology Thesaurus for terms describing the materials and techniques used in making objects. This standardization is especially important for the development of computer databases describing collections. Collection databases allow for speedy searching, sorting, and retrieving of object information for research purposes.

ANALYSIS

To place the object in context for interpretive purposes in an exhibit, additional research is often required. Curators may find valuable information in published research on material culture, social history, archaeology, or many other related disciplines. Often original research is needed, and the curator may need to tap primary historical sources for the most relevant local information.

INTERPRETATION

After gathering and analyzing the information the researcher applies that knowledge to the questions he or she wishes to answer. Interpretation adds meaning and places the study of an object within the larger context of history. Interpretation must then be clearly communicated through such media as books, articles, exhibits, or electronic media. Material culture is the basis for most history museum exhibits. When visiting history museums it is important to consider how material culture is interpreted through exhibits. What story is being told? Why were these objects chosen for display?

3

A CASE STUDY IN THE

INTERPRETATION OF MATERIAL CULTURE The At Home in the Heartland exhibit at the Illinois State Museum provides a case study for the use and interpretation of material culture in a community context. In this case the community is defined as the state of Illinois. At Home in the Heartland tells personal stories of home life in Illinois through material culture. Because the earliest human settlements in Illinois are interpreted in the Illinois State Museum by the Peoples of the Past exhibit in the Anthropology Hall, At Home in the Heartland starts with the French settlements in the 1700s and continues to the 1990s. The major theme of the exhibit is choice and the factors that influence choices. Choices are interpreted in the exhibit through the real-life experiences of ordinary people from Illinois' past. Ambrose Moreau, a French farmer in Prairie du Rocher in 1748, needs a table for his kitchen. What choices are available to him? He must either hire a carpenter to make one for him, make one himself, or buy a used table from an estate sale. There are no stores in French colonial Illinois. Anne Marie Jones is considering what wedding gift to buy for her daughter who is marrying a young lawyer with political ambitions. What gift would convey the social status of the family in Springfield in 1880? A large silver-plated tea set? A large set of imported Chinese porcelain dinnerware? A large set of stylish pressed glassware in the Westward Ho pattern? Eva Buxton is excited about having electricity in her rural home for the first time in 1940. What electrical appliance should she purchase first? A refrigerator, a washing machine, a vacuum cleaner, a toaster, or an iron? Exhibit labels encourage visitors to participate in the choices and to think about the possible influences on those choices. Those influences include availability of goods and services, economics, cultural values, standards of taste, personal abilities, and personal preferences. Every object in the exhibit has a label that offers information about who made it, when and where it was made, materials and techniques of its manufacture, and the history of its purchase and use. In addition, information is offered about its significance in the broader areas of social, technological, and economic history. Hundreds of objects from the Illinois State Museum's large historical collection were selected for this exhibit because of their documented use in Illinois and their importance in telling the story of Illinois domestic life. Analysis of those objects involved studying primary sources such as Illinois estate inventories, archaeology, account books, newspaper advertisements, photographs, family histories, and oral histories to document the use of specific artifacts in Illinois. In French colonial Illinois, legal documents listed the contents of a person's home when he or she died for the purpose of settling the estate. Estate inventories provide a detailed record of the objects found in the home and often include values placed on the objects by an appraiser. Those records can be very revealing. For example, Marie Catherine Baron, a Kaskaskia Indian woman married to a French man, seemed to live a French lifestyle. Her estate inventory included crystal goblets, linen table-cloths, and clothing trimmed with silver lace. One of the most highly valued objects in her estate was a bedstead and bedding. Marie's estate inventory provided the basis of an object display in At Home in the Heartland and an interactive device exploring the relative value of objects and goods in eighteenth-century Illinois. Estate inventories were written from the eighteenth century into the mid-nineteenth century. Most of the later inventories are brief, if they exist at all. 4

Historic archaeology served the material culture research needs of the At Home in the Heartland exhibit in several ways. Very few eighteenth-century artifacts have survived from French colonial Illinois. Archaeology at eighteenth-century French village and fort sites provided remnants of French faience (ceramic) plates and green-glass wine bottles. Skilled modern-day craftspeople using eighteenth-century methods re-created those objects based on those remnants making it possible to complete the visual image of French colonial lifeways. Historical archaeology at early-nineteenth-century homesites documents the widespread use of English ceramics in Illinois homes. Ceramic shards reveal the types of ceramics used hereeven popular makers and patterns. Such evidence documents the availability of specific whole ceramic objects (now found in museum collections) in Illinois. The objects can be used to illustrate the dominance of English ceramic production in the Illinois market and the impact of the American market on the design of ceramic patterns in England. The English potteries even created designs celebrating American victories over the English in the War of 1812! Store account books provide a basis for establishing the availability of certain objects in Illinois; however, most of these accounts do not offer important descriptive information. The typical level of description offered is "blue dishes." Family account books offer case studies of purchases made by a family.

5

Newspaper advertisements from the early 1800s in Illinois list new stock arriving in stores, describe homes for sale, and provide clues to trade patterns. Often, half of a newspaper's copy was advertising. Advertisements in the 1840 Alton Gazette mention Pittsburgh as the source of many iron objects for sale. Another advertisement mentions a merchant's willingness to accept country produce for goods. When photography became available in the late-nineteenth century, it provided important new visual records of home life and material culture. Interior photographs of homes usually document the homes of the wealthy. Fortunately, a few photographers associated with relief agencies chose to document the overcrowded tenements of Chicago workers. (See photo below made in the 1930s.) Oral histories are also an important resource for recording material culture information. The interviewer may elicit in-depth responses to questions about how people thought and felt about objects in their lives. Personal memories add color to other historical records. Researchers conducting material culture studies should use every available resource. The object alone will not reveal its complete meaning in society. Researchers must be aware of the limitations and biases of sources. Information and activities regarding those sources are available to teachers and students in the "Clues to the Past" sections of the At Home in the Heartland Outline exhibit available on the Internet. This extensive Web site offers many activities involving material culture and includes photographs of objects in the exhibit. The web site's address is http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/athome/welcome.htm

Photo courtesy of Illinois State Historical Library

6 In studying material culture, it is important to examine objects closely. Studying the real thing is far more revealing than studying a picture of an object. For many practical reasons, access to museum collections not on display may be difficult to arrange for school-age students. Important lessons can still be learned from studying the material culture that surrounds us every day. By visiting a flea market or bringing objects from home, students can practice the five levels of material culture study-discovery, identification, classification, analysis, and interpretation. From this experience with modern objects, students will also gain a greater understanding of the continuity of history and of their own place on the continuum.

Click Here for Curriculum Materials 7 |

|

|