|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

We can learn much about the past by studying textiles. People slept under them, ate on top of them, and even peered from behind them to observe what was going on outside, just as we do today. Most local history museums are filled with many fine examples of textiles. By studying the textiles we can learn about the lives of the people who owned or made them and compare their beliefs and lifestyles with ours.

The majority of textiles found in a local history museum will date from the Victorian period (named after Queen Victoria of England, who reigned from 1837 to 1901), a real golden age for textiles. The Industrial Revolution had considerably reduced the cost of fabric, and although it was still expensive, a wide range of goods was available from which people made useful household items. Before industrialization, much time was spent producing cloth through the labor-intensive processes of spinning and weaving. You might find some examples of homespun cloth in museums, but by the time most historical societies started collecting, evidence of the pioneering period was lost. And by the mid-nineteenth century the railroad so quickly delivered merchandise that even the smallest dry goods stores in prairie towns could be stocked with reasonably priced ready-made fabrics from the East. Textiles played a very important role in the Victorian household. Expensive fabrics were used to cover windows, beds, and tables, while the rags washed dishes and cleaned up spills. It is not the hardworking textiles that one finds in the local history museum, just as one is unlikely to save a dish rag or paper napkin. Instead, one finds textiles that were hand-made or expensive and pretty and decorative. These were the artistic pieces of the home, lovingly made, treasured, saved, and valued from one generation to the next. In the following article, several examples of Victorian textile artifacts found in the Aurora Historical Society's museum collection are illustrated and discussed. Although handmade items are unique, each artifact selected represents a category in which typical examples can be found in most local history museums. The textiles that have been selected for discussion include samplers, quilts, coverlets, handkerchiefs, and antimacassars. SAMPLES During the Victorian period, it was very important for a woman to know how to sew. A woman who did not know how to sew was considered poorly educated. From girlhood, she was taught skills, including sewing, that would aid in the successful running of a household. Just as she would be expected to help peel potatoes before the evening meal, daughters were given needle and thread to help their mothers with the endless family sewing. Mother was responsible for all the family sewingócreating new garments, making curtains, decorating linens and bed coverings, and mending and remaking torn or worn items. Tasks were divided according to skill level, with the plain sewing going to the children, while mother supervised and tackled the more complicated projects. Most girls

36

learned to sew at home from their mothers. But as a daughter got older, her sewing skills might be refined by sending her to classes to learn fancy stitching. One of the typical exercises done by students receiving a more formal education was the making of samplers (Figure 1).

To us, samplers seem to be merely embroidered pictures, but they were much more. Instead of recording lessons in a notebook, samplers were stitching lessons practically applied with colored floss to linen fabric. Counted cross-stitch was a popular stitch used to make samplers. In this example, see how the student carefully worked letters of the alphabet in different sizes and fonts inside decorative boarders. Samplers could also include numbers, patterns, and sayings. The maker would often stitch her name, age, and the town in which she lived, just as Eliza Ann Marlett, aged 10, did on her Aurora, Illinois, sampler of 1838. While the sampler was being made, it could be easily rolled up and stored in a work bag that could be carried to a friend's house or stitched whenever there was some free time between other household chores. When the sampler was complete, it could be used for reference when an initial or decorative motif was needed to embellish other household textiles. Counted cross-stitched letters were often used to identify table linens, towels, or shirts in the laundry and to make them look attractive. Although samplers may have started out as a way for daughters to learn fancy stitching, their tiny, neat stitches became works of art and a source of family pride. Many parents lovingly framed their daughter's samplers and hung them on parlor walls to be admired and complemented by all who came to visit the best room in the house. QUILTS For centuries, quilted bed coverings have been made to help keep people warm at night. Victorians had a great variety of quilt patterns and styles that ranged from simple patchworks to complicated "crazy" quilts. Quilting is the process by which a top layer, called the face, is stitched to a bottom layer, called the backing. Between the two layers is placed a fluffy material, called batting, which gives the quilt additional warmth and fullness. The three layers are held in place using vertical stitches. Very often the face will not be made up of one continuous fabric, but of a variety of fabrics cut into beautiful shapes and patterns. The quilting stitches that hold the three layers together often outline each individual fabric piece. The most common type of quilt is called patchwork, as illustrated in the doll quilt shown here (Figure 2). These quilts were often called "scrap" quilts because they were made using a great variety of fabrics, usually odd bits left over from clothing construction projects. It was considered wasteful to throw away even oddly shaped fabric pieces because they could be put to good use by making a quilt. Scraps could be cut and pieced to create beautiful shapes and patterns. Geometric patterns were popular, having set designs with names like

37

"baby block," "lone star," and "double wedding ring." In different regions, some patterns became so popular that historians can tell by its appearance and quilting technique where the quilt is from. Patchwork quilts were popularly made throughout the Victorian period, and many different pattern styles are available to see and study.

The crazy quilt was a very popular pattern in the last two decades of the nineteenth century (Figure 3). The crazy quilt patchwork has a richer appearance than its cotton cousin because its scraps consisted of silk, satins, and velvets, all popular dress fabrics of the time. Satin and grosgrain ribbons were also added. The most distinctive feature of the crazy quilt was the contrasting, multi-colored, decorative embroidery that was applied to embellish the surface. Feather, button-hole and satin were popular outlining stitches, and flowers, initials, rings, animalsóeven portraitsócould be used to embroider inside shapes. At first glance, crazy quilts give the appearance of complete disorganization, fabrics arranged in a haphazard fashion. This is partly true. The essence of a crazy quilt was to make the oddly shaped pieces dictate the pattern, instead of cutting the pieces into orderly geometric shapes. Your artistic flair, not a rigid, set pattern, was the driving force behind the crazy quilt. But if you were lacking in creativity, there were several ladies magazines, such as Harper's Bazar, The Delineator, Godey's Ladies Book, and Peterson's Magazine that gave instructions for crazy quilts and every other needle work project imaginable. Signature or "friendship" quilts utilize embroidery, but it was used to outline signatures rather than to add additional embellishment. This style of quilt served the same purpose as an autograph book. The squares contained signatures of family members or friends that were usually embroidered with brightly colored floss on a light-colored ground so the signatures will stand out. Often the quilt was a group project, each person being responsible for decorating and returning her square. When pieced together, the finished quilt would be a wonderful, sentimental keepsake. It was a memento of friends living far away or a creative way to record your family tree (Figure 4). Making friendship quilts was a popular activity for women's groups. The quilt in Figure 4 may have been made to celebrate a church anniversary by recording its members names or used for a fundraising raffle. (Quilt raffles were good money makers for the church.) Or, it may have been made purely for the fellowship opportunities quilting provided. Quilting parties, or "bees," as they were called, brought women together and allowed them to exchange ideas and socialize. Many hands not only speeded up the sewing process, but provided a bit of fun to an otherwise time-consuming, repetitious process. Although quilting bees were organized for a practical purpose, they were also a good excuse to get together, talk, and enjoy each other's company.

38 COVERLETS Coverlets are a type of bed covering often confused with quilts, but the two are easily distinguished. A quilt is like a layer cake, with all layers being stitched together, whereas, a coverlet is a continuously woven spread (Figure 5). During colonial times, coverlets were woven in the home on simple looms. Few examples survive. In a local history collection in Illinois, one is more likely to find a Victorian coverlet made by a professional weaver or one later by machine. A local weaver could offer personalization in design with the addition of clients names, significant dates, and desired patterns. Some people helped defray the cost of the coverlet by supplying home-grown linen or wool to the weaver. A very popular style of coverletósummer/winterówas commonly colored blue and white or red and white. The weaving technique allowed the coverlet to have a "double face," making it completely reversible with the pattern in negative on the other side. These coverlets were used all year round, the white background representing summer and the dark, winter.

HANKERCHIEFS It is hard for us to believe the great variety of Victorian handkerchiefs, especially since disposable paper tissues have made them practically obsolete. In the past, however, a woman would not be considered properly dressed without a clean, freshly pressed handkerchief, the most beautiful ones being used for special occasions. Pretty handkerchiefs were a prized birthday or holiday gift, and decorating them was a good way to show off your hand skills. Linen handkerchiefs could be decorated in numerous ways. It was very popular to embroider initials or monograms in the corners. This type of decoration was also applied to table linens as well. Handkerchiefs could also be edged with handmade and machine-made laces, crochet or tatting (Figure 6). Tatting was a common decorative handkerchief boarder, its lace-like appearance was made using an oval-shaped shuttle. Homemade and machine-made handkerchiefs competed. The handkerchief in Figure 7 was made to be sold as a souvenir at the 1893 World's Fair or Columbian Exposition held in Chicago. From all over Illinois, many people traveled to visit the marvels of the fair and bought and saved souvenirs of their trips. The handkerchief is a printed souvenir or commemorative type. It gives a bird's-eye view of the fair's many exhibition buildings printed in black on white silk with a red border. This style of handkerchief has been printed and sold since the eighteenth century to commemorate a great variety of historical events. Another style is lace-edged linen with an embroidered figure of Christopher Columbus surrounded by the words World's Fair, the date, and flowers. Mourning handkerchiefs (Figure 8), as well as mourning crepe, mourning veils, mourning clothing, and other mourning- related artifacts, can be found in many museum collections. These simple handkerchiefs consist of a white linen or cotton center with a one-inch black border. Examples of hand-stitched and printed black borders can be found. Mourning handkerchiefs

39

became fashionable as more elaborate funerary customs grew during the late Victorian period. The death of President Lincoln helped to spread the wearing and making of special mourning textiles and accessories. Although making handkerchiefs could be a relatively easy project when compared to making a quilt, by the end of the century most women stopped making their own, and instead bought them ready-made. Store-bought ones were inexpensive, pretty, and did not require any time to make.

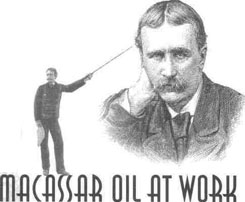

ANTIMACASSARS Antimacassars were used on the backs of chairs to prevent a man's macassar oil (hair dressing that was used to slick back the hair) from soiling the good, velvet parlour furniture. As antimacassars grew in popularity, matching sets (one to cover the chair back and each chair arm) were used to protect the furniture from soil and wear. Antimacassars extended the life of the furniture since they could be laundered when dirty. Antimacassars had a lace-like appearance and could be made in a variety of techniques that included lace, crochet, tatting, or knotting (Figure 9). There were numerous pattern books with instructions on how to make them at home, and they were available ready-made at dry-goods shops. Many other domestic textiles resemble antimacassars. Similar patterns, techniques, and materials were applied to dresser scarves, table runners, table cloths, doilies, and piano scarves. The Victorian home always had some kind of textile to decorate and protect the surface of the furniture beneath it. Many examples of interesting textiles provisioned the Victorian home. It is hard to believe that by the end of the Victorian period, that what had once been an activity was so necessary that it nearly occupied a woman's every spare moment had become a hobby. The Industrial Revolution, which changed society from agricultural to urban, also changed consumer goods from homemade and handmade to store-bought and machine-made. It was no longer important for a girl to know how to sew, do fancy embroidery, quilt, knit, make lace, or tat. And yet textiles are still an important part of our lives today.

Click Here for Curriculum Materials 40 |

|

|