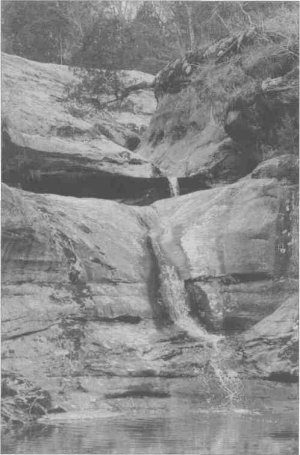

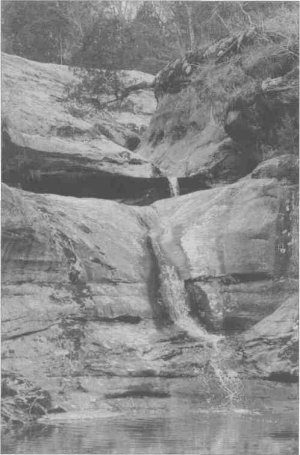

Waterfall Double Branch Hole

Waterfall Double Branch Hole

16 / June 1999 Illinois Issues

Bill Lambrecht is an Illinoisan and a Washington-based reporter who writes about environmental issues for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. His last article for Illinois Issues, " Why the world worries about our corn and beans," appeared in November.

Story by Bill Lambrecht Photographs by Gary Kolb

A top his Tennessee walking horse, Larry Flynn has galloped the back country from Texas to Arizona and camped on many a trail along the way. But to Flynn and his horse, Good Time Gal, nowhere matches the Shawnee National Forest in southern Illinois for pure riding joy. "You have just so many things to see, from flat ground to hills to really rocky country. We've got some of the best riding there is," says Flynn, 63, an insurance agent and member of the Pope County Chamber of Commerce.

No longer is the Shawnee's appeal to the equestrian set a secret. This month, Flynn will join hundreds of riders from around the country who will descend on southern Illinois for a ride in the Shawnee, which is advertised nationally by the American Quarter Horse Association. At the end of July, the Shawnee will be the venue of an even bigger event: a nine-day trail ride that is expected to draw more than 2,000 horses.

These days, Double Branch Hole, Jackson Hollow and the Shawnee's fetching waterfalls, deep pools and natural plunging escarpments ring with the year-round clomp of animals and commands to mount up. These are the sounds of a popular new recreation source in southern Illinois. But the explosive growth of horses also is generating the biggest land-use tussle on the Shawnee's 280,000 acres since the debates over logging. The U.S. Forest Service, which looks to be surrounded, is contemplating decisions likely to displease riders and conservationists alike.

In the past decade, the Shawnee area has seen a proliferation of "horse camps" — camp- grounds that cater to riders with stables, showers and even restaurants. The 25 or so camps that have sprung up in and around the Shawnee have made horseback riding accessible to more people than ever and bolstered an economy that needs bolstering. When Illinois was born, its far southern reaches were blessed with neither the coal seams nor the fertile black soils that gird points north. Instead, the region known as Little Egypt got thin soils and stunning scenery.

All that horseback recreation may be scads of fun and lucrative for some. But it is far from universally welcome, even if it means cash riding into town in $35,000 double-axle pickups and $65,000 sleep-in horse trailers. This explosive growth in Shawnee riding has provoked conservationists, who say that horses and their human companions are spoiling lands where people commonly gather and threatening even more sensitive tracts supposedly off limits.

The Shawnee, like most of America's 154 national forests, remains embroiled in the furor over logging's future. But since Shawnee timber cutting was halted by a court injunction, horses — along with all-terrain vehicles — have emerged as the Shawnee's most lively controversy, involving every level of government and advocates on all sides.

The Forest Service's decision to close 40 of the Shawnee's designated natural areas to horses and other disruptions has enraged the local horse industry, sending it hunting for powerful national allies. That's closing in a technical sense because people continue to use those areas.

Meanwhile, conservationists are upset about the absence of a forest-wide crackdown on abuses and downright lawbreaking. They point to the recent and troubling specter of contamination and smashed vegetation spoiling the

Illinois Issues June 1999 / 17

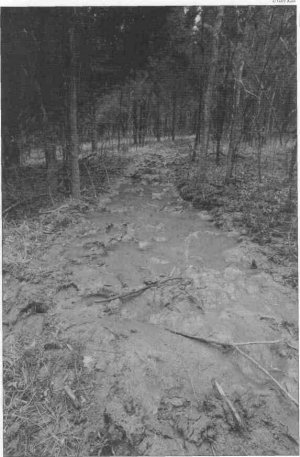

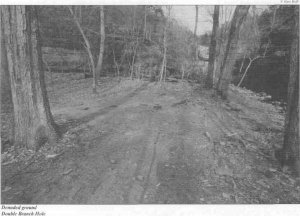

Trail damage Jackson Hole

18 / June 1999 Illinois Issues

Shawnee's special places.

Both sides make a case that the Forest Service is failing.

The battle over horseback riding in the Shawnee — one of the nation's smallest national forests — has the makings of an intractable conflict that will rage for years. To wage their legal fight, riders and local businesses have summoned assistance from the Moun- tain States Legal Foundation, which is challenging the Forest Service's right to keep "natural areas" off-limits.

This new twist has hardened the sentiments of environmental advocates, many of them Sierra Club members, who are aware of the Colorado-based foundation's reputation for whittling away at environmental rules on behalf of corporations and property owners. Mountain States, a law firm founded by conservative beer magnate Joseph Coors, is known for challenging federal intrusion into farming, ranching, mining and timbering. It was run for years by James Watt, the combative Interior secretary in former President Ronald Reagan's administration who later pleaded guilty to misleading a federal grand jury investigating influence-peddling.

Bill Blackorby of Eddyville is among those hoping Mountain States prevails in arguing that the Forest Service can't rightly designate as "natural areas" once-settled strips of forest with remnants of buildings and roads. Blackorby is president of Shawnee Trails Conservancy, a pressure group organized to force the government to permit as much access as possible to riders, ATV operators and others. He and his wife, Cheryl, also own Circle B Ranch adjacent to the Shawnee, hosting visitors hauling their horses to the national forest.

Blackorby sees a pair of dominant factors in the Shawnee struggle: unfounded fears of conservationists — "Radical Environmentalists," in upper case, he calls them in his newsletter — and the Forest Service's failure to build wanted trails. He often makes his case in economic terms: "They talk about greedy campground owners. But when [riders] pull into Marion or Harrisburg or Golconda, the first thing they do is get groceries. Then they pull into a gas station and take 60 to 70 gallons. They all go to the restaurants, the antique stores and they stop at the Wal-Mart," he says, figuring these visitors spend about $65 a day.

Who are these Shawnee invaders who will be arriving from 20 or more states in the weeks ahead? Blackorby says he gets doctors, lawyers and a lot of business sorts, those who can invest as much in horses and big toys as most people sink into a home. Older folks, too; people who have had bypasses and hip-replacements and who would not enjoy the Shawnee's splendor if not perched on a half-ton animal. They pull into camp with those fancy rigs and pay $16 or so a night for water, electrical hookup, showers and pens.

Blackorby takes issue with those who trumpet the damage. His conservancy has hired some high school students to shore up eroded trails. He knows riders who tote plastic bags to tidy up. Sometimes you can ride a mile, he says, and find nary a soda can. "We want to protect the forest, not damage it."

Ed Cook says a Forest Service worker once described to him a map of horse trails in the Shawnee. There were supposed to be only a few; instead, the trails looked like someone dumped a plate of spaghetti.

Cook, 51, is among many people who went to Southern Illinois University in the 1960s and never left. "An old hippie," he describes himself. He's also a contractor and a Sierra Club stalwart who has learned the ways of the woods living deep in the Shawnee in a place he will only describe as near Panther's Den.

Hiking with his wife Gale and leading Sierra Club excursions, Cook has crawled over the Shawnee's most pristine spots. The damage he reports differs from riders' claims in the way a Clydesdale compares with a Shetland pony. He describes a scene at a Shawnee spot with a waterfall and sheltered cave: "Water that used to be crystal clear is muddied and loaded with nutrients [from manure]. All the nutrients have turned the rocks rainbow colored with red and green and brown algae growing like it's industrial wastes. Trees smaller than eight inches around all are dead from having horses tied up to them."

In a word, Cook sums up the dramatic changes the Forest Service must cope with as it writes a new plan that will serve as the blueprint for the Shawnee's future: "Unbelievable."

The debate in the Shawnee mirrors the conflict sweeping a government agency in transition. To most people, the name Forest Service conjures a vision of deep-woods protectors, a legion of rangers in stiff hats who embrace environmental advocacy with the fervor of their most famous symbol, Smokey the Bear. Conservation is part of it, but the job description is a whole lot broader.

Under long-standing orders from Capitol Hill, America manages the forests it owns not just for conservation and recreation but for business opportunities, often heavily subsidized, for companies and individuals alike.

From the redwood lands of northern California to the pine stands of Virginia's Skyline Trail, timber extraction always has provided the Great Controversy of publicly owned forests. In the Shawnee, before the advent of horse camps, dirt bikes, three-wheelers and now four-wheelers, the clarion cry

Illinois Issues June 1999 / 19

of conservationists was limiting the board-feet of lumber harvests. And publicly owned forests serve up more than wood: There's oil in those hills, not to mention odd minerals like fluorspar, which has been mined around the Shawnee. People often forget that public lands are a business, one that's run by the federal Department of Agriculture, a noted promoter of commerce, rather than our parkstending Department of the Interior.

Recently, this nation has begun re-examining the wisdom of turning forest lands into industrial zones. Both the impact and the economics of subsidized extraction have been questioned; in 1997, for instance, taxpayers lost $45 million on commercial logging when road building and other costs were factored in, according to a study by the Wilderness Society. The Shawnee ranked near the bottom out of 83 losing propositions as a result of the injunction that has forestalled logging.

As with other cases of so-called corporate welfare, perennial reports of questionable subsidies for wealthy timber companies haven't set well with taxpayers, many of whom already understood the ravages of clear-cutting. In one national poll last year paid for by the nonpartisan Washington- based interest group Taxpayers for Common Sense, 69 percent of Americans favored ending all logging in national forests. The upshot of changing public perceptions is a seemingly new attitude in Washington toward national forests, a view that is being articulated by U.S. Forest Service chief Mike Dombeck.

This spring, Dombeck, a Wisconsin native, called for "an invigorated national land ethic" that would restore clear-cut lands and protect endangered species. Ending logging is too extreme, Dombeck said. But recreation, not logging and grazing, will be the prime focus of federal activities. And instead of measuring efficiency in board-feet targets and cattle counts, Dombeck asserted, the Forest Service will evaluate employees on how successfully they stemmed erosion, improved wildlife and contributed to the health of forests. "Americans want and expect clean water and healthy lands," he said.

A changing forest politics has been showing up in new forest policies. Earlier this year, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Dan Glickman declared a moratorium on new road building on more than 30 million acres of government-owned forests. In April, President Bill Clinton's administration placed 234,000 acres of Alaska's Tongass National Forest off-limits to logging and development.

The new attitude in Washington may or may not erode like a forest stream bank when a new administration takes the reins of the federal government. There's skepticism among conservationists. "He [Dombeck] is a man with vision; he's the first Forest Service chief who has had a vision and could articulate it," says Michael France, the Wilderness Society's director of national forest programs.

But France, like other conservationists, is wary. He worries that an entrenched "old guard" in the agency is biding its time, waiting for the days of heavy extraction to regain favor. "He [Dombeck] is one person with a very small cadre around him," France says.

"The Forest Service shares the same problem as the Titanic; its rudder is too small."

In the Shawnee, the Forest Service's Rebecca Banker has noted the appearance of horse camps while driving from her home in Eddyville to the main office in Harrisburg. Banker is the agency's public relations specialist. But there are times, because of vacancies and absences, when she wears the title of acting forest supervisor. That means she runs the show. Everywhere, the Forest Service has the Solomon-like task of balancing the conflicting desires of people starving for the outdoors. And right now, Banker sees a stark contrast in those desires. "There's a group that truly believes that they have a God-given right to ride their horses on every square foot of forest out there. And then there's the other side, which believes that we must close the natural areas."

The Shawnee controversy sparked anew this spring after a Forest Service letter to the public. The "Dear Interested Citizen" letter mailed out in March advised that Shawnee administrators were proposing to construct equestrian trails in two natural areas, Double Branch Hole and Jackson Hollow. "The objective of this project is to protect those features and intrinsic values that make the natural areas special while establishing safe and maintainable trails that provide users with a quality recreational experience," it read.

Amid the stilted writing were words that inflamed both conservationists and riders. After stating its goal of setting up the trails, the letter observed in detail some of the damage that already has occurred. Sandstone glades and cliffs have become eroded. Endangered plant species have become lost or threatened: French's shooting star, black cohosh and Yadkin's panic grass to name three.

The letter goes on to say that if monitoring under a new system finds such damage, whole natural areas could be closed to horses. That warning, like the rest of the letter, reassured neither side. Horse-camp owners do not want to be reminded that areas could be closed to them for good. And conservationists, knowing that so little monitoring occurs presently, doubt the Forest Service's resolve to protect the integrity of new trails.

You need to look behind many trees to find someone who'll praise the Forest Service. Blackorby, the-horseman, recalls riding in national forests in Western lands and encountering crews of rangers on horseback, shovels behind their saddles, looking for trails to repair. Among the Shawnee's welcome sights, whole crews assigned to trail upkeep isn't one you'll often see.

Meanwhile, the Forest Service has almost no law enforcement to corral careless horseback riders and ATV jockeys. In 1992, Shawnee planners designated 286 miles of forest for ATV trails. Those trails are another component of a Shawnee blueprint held up in court. Lacking designated trails, ATV riders tear through the forest with abandon, undaunted by the Shawnee's two-man law enforcement team. It's as though the government has dispatched Barney Fife to close down Chicago's

20 / June 1999 Illinois Issues

crack houses.

Former U.S. Rep. Glenn Poshard sponsored the Illinois Wilderness Act in 1990 that set aside tens of thousands acres of land for protection. Poshard, a Marion Democrat who lost his bid to become governor last year, treads a distinctly middle ground between unyielding environmental advocacy and defense of business and property. These days, Poshard is troubled not just by the damage in the Shawnee but also by the Forest Service's incapacity to jump in the saddle and take control of its controversies.

"You have all of these ongoing problems that seem to never get resolved, whether it's horse camps, ATVs, safety, managing recreation or actually managing the logging. Things just never get resolved," says Poshard, who now is a professor and special assistant to the president at John A. Logan College in Carterville.

Land-use and development squabbles have similar lives: recognition of a problem, then anger and name-calling, followed by partnership and collaboration that yield a solution that mollifies some, but not all. The cycle may repeat itself. In Shawnee National Forest, the debate over horseback riding appears lodged in an early, vindictive stage when motives are challenged, not just facts.

To riders like Larry Flynn, preparing to saddle up Good Time Gal for a new season of trail rides, the critics are "tree-huggers" who want to shut down the forest for anything but their selfish pursuits. "The tree-huggers say they want to go back like it was, but back when Lewis and dark camped here, there weren't even many trees," he says.

Meanwhile, to Sierra Club members like Cook, the issue is one of greed. He points to a fundamental reality that links this debate with many a national forest land-use ruckus: profiting from public resources, as he puts it, while putting little or nothing back.

As the Forest Service confronts an issue that promises to roil both sides well into the new millennium, the Shawnee's Rebecca Banker sees the battle as classic, if not inevitable. "You're looking at a very small forest in a state where there isn't a whole lot of forest, so there are huge demands from the public on a very small amount of land," she says.

"Any time you have a situation like that, you're going to have conflict."

Illinois Issues June 1999 / 21