|

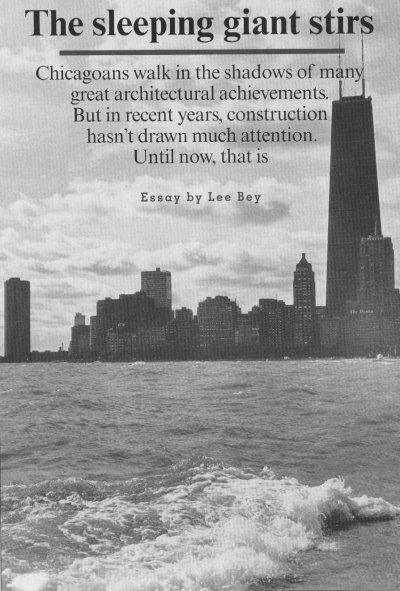

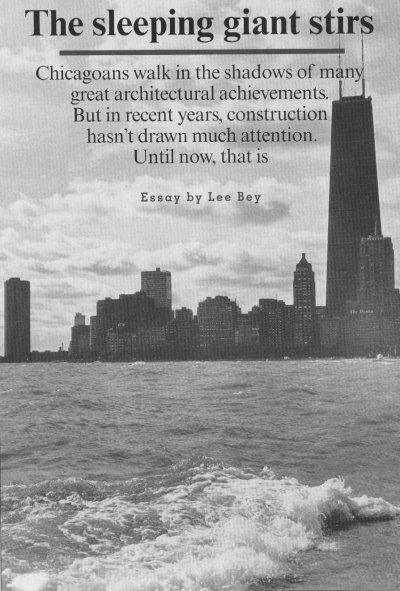

Chicago is used to world-class architects walking its streets. The likes of Helmut Jahn live in its confines; the shadows of Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Harry Weese and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe loom.

But the big city is not so jaded that it couldn't get excited when architect Frank 0. Gehry came to town last month. The southern California genius, who has been favorably compared to Wright, unveiled an impressive model of a bandshell and music pavilion that he designed for the city's Millennium Park, now under construction in a section of famed Grant Park.

Gehry is a hot architect, if there is such a thing. The 70-year-old design master won worldwide acclaim and attention with his new Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. The silvery, spellbinding structure has been among the most-widely discussed buildings of the decade and almost single-handedly reshaped the image of the once-troubled Basque city of Bilbao into that of a sophisticated international metropolis.

Bilbao needed Gehry. But does Chicago? Yes.

Gehry's entry threatens to break the design malaise that has gripped the city. Chicago has a glorious architectural legacy, one that gives the city its strength and international status. It's a point of civic pride. But the dirty little secret is that Chicago has failed in recent years to break new architectural ground.

Viewed in the cold light of history, the evidence is especially jarring. The city began the century with grand downtown skyscrapers such as the D.H. Burnham & Co.'s Reliance Building and Wright's work in Oak Park. Chicago then pulled off a midcentury encore with sleek, pioneering steel-and-glass structures such as Mies' Illinois Institute of Technology campus and Skidmore Owings & Merrill's John Hancock Center and Sears Tower. But the city will close out the century without having produced a significant class of top-drawer architecture in more than a generation. Gehry, a superstar of architecture,

|

16 December 1999 Illinois Issues

|

James R. Thompson Center

|

could be just the person to jolt things back to life.

"It's a challenge to have the shadows — the ghosts — of Mies and Wright looking over your shoulder," says Chicago architect Stanley Tigerman, a Gehry friend. "But I really believe Frank is a great architect, not a good architect, but a great architect working in a city that is loaded with great architecture."

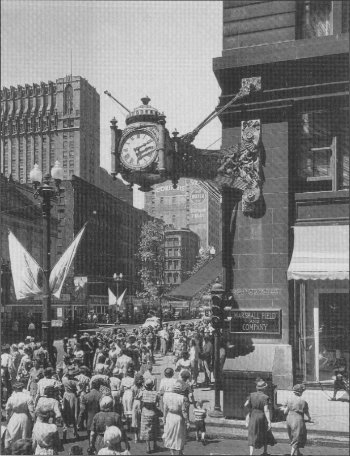

What a place turn-of-the century Chicago must have been. As the city grew, architects were perfecting the skyscraper as a means of cramming as much commerce as possible into a downtown that was boxed in by Lake Michigan, the Chicago River and its south branch. Residential architects, meanwhile, were quickly reshaping prairies and land voids into suburbs and residential neighborhoods.

Genius was born in the vortex of this activity. Instead of designing the now-demolished Home Insurance Building with thick, load-bearing exterior walls, architect William Le Baron Jenney created a metal frame that bore the weight of the structure.

Because the exterior walls didn't have to help hold up the building, windows could be made larger. And the new buildings could be built higher than traditional structures.

As Perry R. Duis wrote in his 1995 essay, "The Shaping of Chicago," in the AIA Guide to Chicago, published by the American Institute of Architects: "[T]here were almost no theoretical limits to a building's height." The late 1800s saw a spate of architecturally significant buildings that still stand today. Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan's amazing Auditorium

Building — home to Roosevelt University since 1945 — helped usher in modernism, the artistic break from the past.

Adler and Sullivan created a building that is beautiful not because of ornamentation, but because of clarity of design. Space, rhythm, color and form give the 1894 building its charms. Mies would use the same palette 50 years later to create IIT'S miracle of modernism, Crown Hall. The ground-hugging, steel-and-glass (mostly glass) single-story building is home to the university's college of architecture.

|

Equally influential was the Reliance Building at State and Washington. Built in 1895, the glassy and minimalist sky scraper was justly seen as the progenitor of the modern office tower. In the 1930s, the building confounded and fascinated European modernists, who sought to design structurally expressive buildings that were free of frilly traditionalism — only to find that Chicago had such a building sitting in the heart of its downtown for a third of a century.

But these architectural advancements were hard-fought, especially in the wake of the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park.

Planner Daniel H. Burnham, he of the "make no little plans" manifesto, created a scenic fairground of domes and columns - that was beautifully landscaped and built, but designed to resemble Paris after the Renaissance, not the cradle of a modern city Burnham's 1909 Plan of Chicago continued the idea, seeking to create a city of eight million styled like an old European capital.

The fair shaped 30 years of Chicago architecture and did much to color the city's concept of a "good building." Downtown buildings along Wacker Drive answered the call to classicism's embodiment of ancient Greek and Roman styles, with replicated gargoyles and stone columns.

Illinois Issues December 1999 / 17

|

Art Deco, a flashy, streamlined style taken from a 1925 French decorative and industrial arts exposition, would have a brief reign in the 1920s and early 1930s. It would gain some ground on Michigan Avenue north of the Chicago River. It would find a home in the LaSalle Street financial district, producing a stable of swank buildings in the city's mercantile canyon, including the North LaSalle Building — now a Chicago landmark — and the Field Building near Monroe and. LaSalle.

The treasure of the LaSalle Street bunch is Holabird and Root's Chicago Board of Trade Building, an Art Deco tower of power topped with a statue of Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture. The 45-story structure is an upward sweep with dramatic setbacks that serves as a reminder that money makes its presence known.

Outside of downtown, architects such as Wright, Walter Burley Griffin, Barry Byrne and John Van Bergen sought to free residential design from such Victorian constraints as cramped parlors and rooms sealed off from each other by hallways and doors. They created an architecture in which rooms would flow one to another and interior doors were few. Landscaping would be more than green grass and pretty flowers, but a slice of nature snuggled next to the home.

The Great Depression followed by World War II stilled Chicago's architectural march for nearly 20 years. When life resumed in the 1950s, the modernism hinted at in the previous decades began full bore across the globe.

The Prudential Building is a sentimental favorite of Chicagoans because it was the first building constructed after the war, but it is not modernism. The vaguely Art Deco design of the limestone clad Prudential sought to pick up where Chicago had left off before the war and the Depression. It belonged to the past. But its classmate, the Inland Steel Building at Monroe and Dearborn, was the future. Cool, sleek and glassy, the stainless steel clad building was a clear expression of modernism that would mark a new class of influential Chicago buildings.

Mid-1950s postwar prosperity created a confluence of cash and need just as it had existed in Chicago 60 years earlier. In an amazing 15-year run after Inland Steel was completed in 1958, the city gave birth to some of the world's aesthetically pleasing and structurally impressive modernist buildings: the John Hancock Center (1969), the First National Bank of Chicago Building (1969), the Daley Civic Center (1965), Marina City (1959-1968), the Brunswick

|

|

Illinois thinkers

After helping to find the top quark, physicist Leon Lederman is searching for a way to make science understandable to the average citizen. Lederman came to Illinois in 1979 as the director of Fermi Lab in Batavia, where he supervised construction and operation of a high energy accelerator, enabling scientists to begin to understand why matter has mass. His work won him the Nobel Prize. In 1985, he founded the Illinois Math and Science Academy, which develops the top minds among Illinois high schools students. He also helped organize the Teacher's Academy for Mathematics and Science, which aims to retrain Chicago public school teachers in the skills needed to effectively teach math and science.

Milton Friedman arrived in Illinois as a poor graduate student at the University of Chicago. But by 1957, he had set the national agenda for economic research with his argument that consumers base decisions about consumption on expected long-term income. He garnered national attention with a series of articles that changed the way economists view the relationship between inflation and unemployment. Friedman argued that nominal consumption is determined more by money supply than by government spending. This theory emphasized Friedman's support of laissez-faire economic policy and laid the foundation of the supply-side economic theories of President Ronald Reagan's administration. In 1976, Friedman won the Nobel Prize for his contributions to the field of economics.

Evanston-based historian, author and journalist Garry Wills yanked Abraham Lincoln back onto the national stage with his best-selling book Lincoln at Gettysburg, which won the 1993 Pulitzer Prize. Wills argued that the course of history was altered by the speech in which the Great Emancipator chose to link the nation's birth to the Declaration of Independence rather than the Constitution. It's an important distinction because the Declaration of Independence judges all men to be equal, while the Constitution tolerates slavery. Wills, who received a National Humanities Medal from President Bill Clinton last year, has tackled a wide range of topics, including John Wayne, Jack Ruby and President Ronald Reagan.

The Editors

|

|

18 December 1999 Illinois issues

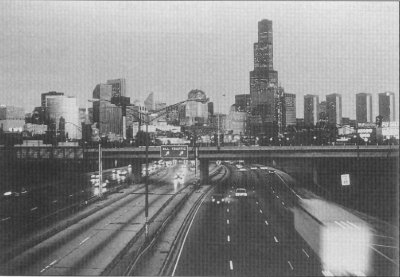

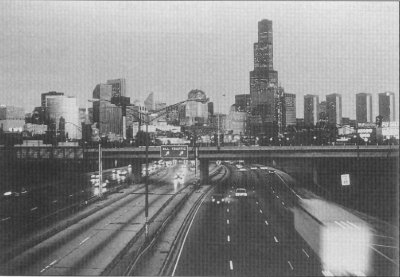

Building (1965), the Chicago Federal Center (1959-1974) and the Sears Tower (1973).

Then it was gone. Economic hard times in the late 1970s certainly played a role in dampening the creation of good new architecture. But buildings didn't improve in the go-go 1980s when money was plentiful. More than a few unimaginatively designed office buildings popped up in the west Loop on South Wacker.

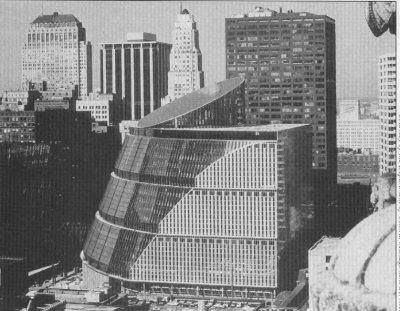

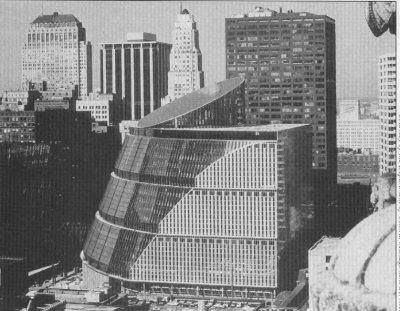

The State of Illinois Center designed by Helmut Jahn seemed destined to revive Chicago's architectural fortunes. It was a daring attempt to redefine the concept of the government building. Jahn created a structure with an expansive, glassy atrium. Instead of hiding workers behind walls and oak doors, he opened up the works, creating large reception areas that overlooked the atrium. Painted in a stylized version of red, white and blue, the building was like no other in Chicago.

|

Marshall Field's

|

But when the State of Illinois Center came in over budget and riddled with heating and cooling problems, it cast a public pall over the building and its unconventional design. Architectural innovation suddenly became a scary concept.

The retreat to familiar ground was on, hence the Harold Washington Library, built in 1991. The library's design is not daring. It's "comfort architecture," with its design borrowed from bits of Chicago's architectural past. The library is a pastiche of turn-of-the-century architecture stripped of its original purpose.

Chicago architects continued creating great buildings, but their work was in other locales, such as Germany, England, Singapore and Shanghai.

Mayor Richard M. Daley likes architecture and urban design. If his father, "Daley the Builder," oversaw the city's impressive postwar building boom, "Daley the Beautifier" has come along a generation later to tidy things up.

His administration has beautified city streetscapes, planted trees and kept the joint clean. Hardly a big project goes by that Daley does not personally check to make sure it passes his design muster. Moreover, his administration seems willing to push developers and architects to create better buildings. Chicago's architectural legacy is one worth preserving because the city's identity is so intertwined with it.

|

Through decades of urban flight, bad schools and intermittently corrupt politics, tourists and residents could always point to the world class architecture and think, "This is still Chicago."

It was Daley who approved of Chicago architectural firm Skidmore Owings and Merrill as designers of Millennium Park, a new city park that is being built over a century-old eyesore of a rail yard in Grant Park just north of the Art Institute. Skidmore Owings & Merrill's chief architect, Adrian Smith, suggested importing Gehry to design the pavilion after finding his firm's attempts had "something missing,"

"Initially, I was looking for someone who would be an artist who could do some pieces of sculpture for the stage itself," says Smith. "I had a whole list of people ... it just came to me that Frank's work would be terrific for that area. So I mentioned it."

Gehry's outdoor Millennium Park Music Pavilion is as large as a football field. There is the bandshell topped in curls of stainless steel, fronted by seating for 4,000. Behind the seating, Gehry planned a lawn where up to 6,000 would be able to sit.

The work, as shown in Gehry's models, is a passionate effort that does not stylistically revisit Chicago's past. There are no faux Sullivanesque flourishes or faked-up Prairie School styling, but there is a directness, boldness and honesty that comes from the Chicago tradition.

Not bad for a work that was produced from scratch in a matter of months and comes complete with a state-of-the-art acoustical design.

"They pushed it fast," Gehry says of the city "But I like to work fast."

"I think he stands alone," Smith says of Gehry. "He built a reputation in Bilbao that gives him a unique cachet and a unique ability to sell others."

After Gehry was brought on board last winter, other big-name architects began to find work here. Italian architect Renzo Piano was picked to design additions to the Art Institute of Chicago. Cesar Pelli, who designed Malaysia's Petronas Towers, and Richard Legoretta were selected to design new buildings for the University of Chicago campus. And Skidmore Owings & Merrill announced plans to design a new world's tallest building at 7 S. Dearborn.

Perhaps Chicago, the sleeping architectural giant, is awakening.

Lee Bey is architecture critic for the Chicago Sun-Times.

Illinois Issues December 1999 / 19