Who needs skyscrapers and symphonies when we've got stripped-down, straight-ahead, fill-up-the-shot-glass blues?

Essay by John Carpenter

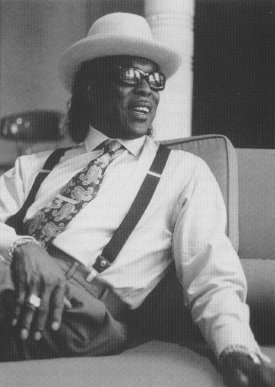

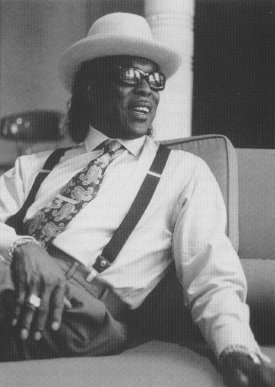

Buddy Guy, Chicago blues guitarist

It was late in the last decade that I came to Chicago on a lark, running away from a relationship and toward who knows what, with the promise of a job at a newspaper I'd barely heard of. My father was driving the rental truck in front of me. And with Boston a few miles in the mirror and Chicago almost 1,000 miles down the road, I had plenty of time to think.

I popped in a tape, instead, the cassette a friend had stuck in my pocket at the going-away party.

"I made this one for you, Carp," he'd said. "You're movin' to a great town."

Going to Chicago, Joe Williams sang. Get that monkey off my back.

I smiled and thought about my new home.

I wasn't thinking about tall build-

20 December 1999 Illinois Issues

"HooDoo Mama," from an original oil painting by John Carroll Doyle ©1994. |

ings or great lakes, world famous symphonies or stately museums. I was listening to a stripped-down, straight-ahead, fill-up-the-shot-glass blues song, and it was about my new home. That's why I was smiling. Lots of places have buildings and museums and philharmonics. But we've got the blues. There aren't but a few other cities that can really say that. And let's be honest, only one of them's worth even visiting. And who wants to go to New Orleans for more than a few days? |

Every immigrant who came to Chicago brought his or her own music. And you can still hear most of it if you know where to look. But it was the multitudes of blacks who came here during two great waves of Northern migrations who brought the music that has stamped Chicago — music that has seeped into the veins of whites and blacks who still tap their toes or clap their hands at any of the classic blues lines.

Between 1890 and 1920, the number of blacks in Illinois surged from 57,028 to 182,274, and the majority of them settled in Chicago. The second wave, between 1940 and 1960, brought another 368,000 blacks to Illinois. Many—Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, "Big" Bill Broonzy — came right out of the birthplace of the blues, the Delta.

The blues came to Chicago by — how else — train. The Illinois Central to be exact. Some people came by bus, of course. And still others may have driven or hitched. But most rode the Illinois Central straight up from the Mississippi Delta, seeking the good, high-paying jobs that World War I and World War II were producing. One of the people riding that train remembers his dad jumping off in Memphis, where the train made a long stop to change engines. Dad was getting sandwiches for the family but wasn't back on the train as it pulled out of the station. The little boy wasn't even 4 years old.

"I was crying and crying say in', 'Daddy didn't make it! Daddy didn't make it!'

"I cried myself to sleep. But my daddy had gotten onto the last car as it was pulling out and he made his way up to our car. When I woke up he was there. I thought it was magic."

That little boy remembers getting off the train at Roosevelt Street Station and, unlike most of the others from Mississippi, heading north rather than south, to the home of a relative near what is now Cabrini Green.

He also remembers running across Wells Street from his job at the Lawson YMCA, standing on a crate to peek into the window of the neighborhood bar, where Muddy Waters or Howlin Wolf might have been playing for drinks.

That little boy is easiest to find nowadays in the Cook County Building, sitting quietly in the back row at a county board meeting.

He is, as a matter of fact, one of my earliest memories of Chicago, an appropriate mix of politics and the blues, and one of the many little reasons I fell in love with the city. It was my first Election Day and I still didn't

Illinois Issues December 1999 / 21

know who was who. But I was voting. And as I scanned down the names, one stood out, a candidate for Cook County Board. I smiled as I punched a vote for Jerry "The Iceman" Butler.

I remember meeting some friends at a bar later in the day.

"What other city can you name," I asked them, pounding my hand on the bar for emphasis, "where you can walk into a voting booth and cast a ballot for Jerry Butler, a man who's forgotten more about blues music than I'll ever know!" And a man who has sold 30 million records and who likely will remind you that it's rhythm and blues that he knows.

He started singing at home and in church, forming the Northern Jubilee Gospel Singers when he was 14, at one point bringing another neighborhood kid named Curtis Mayfield into the group. Within a few years he'd recorded "For Your Precious Love," a million-selling hit, and he was a bonafide musician, playing everywhere. But Jerry Butler was a young man then. The older guys were also playing everywhere, from Maxwell Street to blues joints all over town, mostly on the South Side.

They played at places like the Club DeLisa. And they had names like Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf, names now etched in the canon of the blues.

What Butler remembers about that time, however, isn't just the blues.

Chicago, he said, was alive with every kind of music you could think of, from jazz to gospel, to rock and roll, to classical to, of course, the blues. And while the older folks were listening to the latter the way the Irish listened to their jigs — to connect themselves to home as they settled in to a new place — the young folks like Butler had different ideas.

"The blues was what we were running away from," Butler says. "We wanted the cool stuff."

The cool stuff was a little bit of rock and roll, a little bit of the vocal groups singing their smooth harmonies. But when you took young black talent steeped in the blues and let them try to be cool, the result was what we now call rhythm and blues.

But I'm wandering a bit here. This is supposed to be about the blues. One of the sad ironies of modern commerce is that you know something has made its mark when it starts to get commercialized. And sure enough, all around Chicago are blues bars, most of them touting T-shirts and other tourist gear. But the commercial viability of Chicago blues music is what we celebrate. Sure, you can listen to old recordings of Robert Johnson. Or you can wander into the Kingston Mines or Buddy Guy's or any number of taverns where working men and women are practicing the trade of singing the blues.

You've heard probably more than you're interested in knowing about my move to Chicago and my voting habits. But here was the experience that sold me on the blues and I pass it along because it could happen to you. It still happens to people every day in Chicago.

I was still young and single and doing what young and single people do when living in Lincoln Park — traveling from bar to bar like a herd of cattle, carrying out the drawn-out and generally inebriate mating ritual — which is to say bar-hopping. It was getting late and most places were closing when one friend and I peeled off from the group and wandered into the Kingston Mines.

I protested the six-dollar cover until the doorman menacingly reminded me that the music would be playing for at least another three hours.

I stumbled into the two-room club, letting my eyes adjust to the smoke and haze to survey the crowd. It was mostly white, of course. But it wasn't all white, which made it different from most other places in the neighborhood.

Son Seals was playing in one room, but there were no seats. A waitress who was clearly the kind of girl mother warned me about, asked if we wanted anything and told us that another show would begin in a few minutes in the other room, as soon as Son Seals' set was done. We ordered beers and settled in at a table up front.

In a few minutes, musicians were wandering up to the stage fiddling with their instruments, like a construction crew preparing to get back to work. They looked like people just getting off break, which they were. Somebody got up and told us to put our hands together for the one, the only, Dion Payton, and a lean black man with a large cowboy hat ambled up on stage. And pretty soon we were mesmerized by his soulful guitar and the tightness of the band. You have to remember we were 20-somethings hooked on alternative rock that featured bands who cared more about copping hiply detached attitudes than they did for their musicianship. These guys were tradesmen, plying a craft.

After the set, Dion himself shook our hands and my friend offered to buy his guitar player a drink. He sat down to talk to us, two young, extremely white kids — young newspaper reporters to boot. For us it was like talking to a museum exhibit, a real live blues guy. We started interviewing him, asking all kinds of questions I can't even remember, other than to imagine that they were probably idiotic and maybe even condescending. He indulged us, however.

And my friend asked him what he thought about when he played his guitar.

What were we thinking? Did he think about "the blues," about how difficult it was to be a black man in white America, how tough it was for his parents and grandparents, how he savored the moments when the music could take him away from it all? The guy, whose name we never even got, took a drag on his cigarette, finished the last of his drink and looked at my friend.

"Mostly," he said, "I think about women."

Yep. You can talk about the great migration and read all the books about the Delta blues singers wailing for pocket change on Maxwell Street or cutting legendary blues tracks at Chess Records. It's all there because the blues is as much a part of the history of this city as anything else.

Or you can wander into a smoky bar at three in the morning and strike up a conversation with a guitar player while he's on his break.

John Carpenter is a reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times.

22 / December 1999 Illinois Issues