FIRST HALF OF A TWO-PART ARTICLE by SUE KENNEDY

SUE KENNEDY

Formerly a county government reporter for the Illinois State Register, she writes a monthly education newspaper for the Illinois Office of Education.

Need for land use planning linked to population growth

|

Traditionally, zoning has

been a local function.

Now it is under fire, has

outlived its usefulness,

its critics say. To take

its place, state land use

formulas are urged, and

legislatures, including

Congress, have bills

before them to this end |

|

ZONING is inadequate in regulating the intensity of development and providing for open spaces and preservation of natural resources.

Zoning and planning are not strongly related in most Illinois cities.

Zoning is often used to exclude racial or low-income groups from suburban areas.

Zoning has worked well for planning single-family residences, but falls short in the areas of large-scale, multiple unit planned developments.

Zoning often leads to growth centered around interstate highway interchanges and other major highway routes rather than evenly distributed growth.

Zoning enabling acts for county, township and municipal governments are unnecessarily duplicative with no apparent major differences in purposes or powers.

These charges against zoning are leveled by Illinois citizens in a 1971 Zoning Laws Study Commission survey and reflect a national trend to revamp outmoded land use practices. Local government officials, lawyers, teachers, skilled workers, farmers and businessmen reported their grievances to members of the legislative study commission, chaired by Rep. Eugene Schlickman (R., Arlington Heights). Subsequently, legislation was introduced to repeal present zoning enabling acts, and establish a new formula for Illinois land use. In addition, legislation entered in Congress in 1975 sought to redefine land use priorities to encourage greater environmental awareness. The legislation was designed to nudge state governments from haphazard to coherent land use policy.

Why a new system?

Clearly, the traditional zoning practices that have helped shape the face of this continent are under fire. Why? Many critics of zoning contend that the system has simply outgrown its usefulness. They say that when the cluster of basic zoning ideas was formulated in the 1920's it was to remedy problems vastly different from those we face today. Cities of the early 1900's were nightmares of poorly regulated development with no regard for safety, sanitation and building structure. Dirty factories, overcrowded tenements and widespread disease were the common denominators of city life. Eventually, society saw the need to protect its citizens from such conditions. Hence, zoning evolved as a police power, to be used as a tool to carry out local objectives put forth in a comprehensive plan, a general outline for the physical development of a community. Subsequently, municipalities, counties and townships were delegated individual power by the states.

Today, critics feel that zoning cannot cope with the problems of unbridled growth, urban sprawl and rampant private development. A no-growth attitude is emerging to replace the enthusiasm for community expansion- at-any-cost which was common in the ( 1950's and early 1960's. Sobered by the onslaught of development in major urban areas, citizens residing in pleasant natural settings have decided that compromise can no longer save then communities from urban glut. In Boulder, Colorado, two local organizations forced the first referendum in the nation to limit population size. The referendum was narrowly defeated, but Boulderites did pass a building height limitation which has since been violated, am directed local officials to make a study of optimum population size.

Although the legality of such population control measures is not yet deal statistics on projected population and urban growth have convinced some futurists they are necessary. The U. S. Bureau of Census reports that the

18 /January 1976 / Illinois Issues

|

population will continue to rise at least until the year 2020 even though fertility rates in the United States are beginning to edge below the 2.1 replacement level. Reaching a "zero population growth" (ZPG) fertility rate (2.1) does not mean population immediately stops growing. This will only occur when the percentage of females of the child-bearing age diminishes over time. The fertility rate would need to remain at the replacement (ZPG) level for about 75 years before population growth would actually stop. Population pyramids for the United States presently show a very young population.

Fear loss of farmland

Also, statistics indicate that by the year 2000 urban regions in the United States will occupy one-sixth of the total land area as opposed to one-twelfth in 1960. Approximately 20 million more acres will become urbanized by 2000 A.D. Critics are disturbed because present zoning policies make it easy for developers to obtain valuable farmland through local tax assessments that force owners to sell.

In addition to the fact that land resources are finite, specific zoning practices have been attacked as favoring certain groups instead of all the people in a community. Developers often twist the arms of pliable local officials to put up housing units where no public facilities exist and no provision is made for them. Or, lacking consent, developers sometimes go ahead with a development project and force local approval because it would be too costly for the local community to halt the project. This lack of concern for adequate facilities most often occurs in leisure home developments which may later become part of the community proper. Planners, often answerable directly to local officials, are powerless to effect legitimate planning. Instead, decisions are often made on the basis of a narrow expediency and short- term economic considerations.

Problem of interests

There is also some evidence that zoning often works to exclude the poor by limiting the building of multifamily dwellings in certain areas. In the Zoning Laws Study Commission survey, respondents from Chicago indicated that "the well-to-do are trying to legislate their own conception of life and habitat." The common request was that "the State do something statewide in remov-

|

|

January 1976 / Illinois Issues / 19

'A first step would be for state

governments to conduct research

and do analysis on planning problems

facing communities and make this

information available to local planners'

ing the current parochialism concerning zoning and its inequities in application."

One respondent suggested regional planning commissions be set up in the state to help local government equalize planning for land use so that "an agency larger than the local government could force that government to conform to the same land use controls that it enforces upon its citizens."

Also, with the exodus from city centers to suburban areas, it is clear that land use problems have taken on a more regional significance. Suburban developments are far from places of employment and almost no developers plan for services like medical offices or hardware stores.

Speaking to this problem is a landmark case dealing with the validity of municipal zoning, Euclid v. Ambler Realty, 111 U.S. 365 (1926) which states that in the future there might be "cases where the general public interest would so far outweigh the interest of the municipality that the municipality would not be allowed to stand in the way." According to a survey of the problem for legislators by the Council of State Governments, the fact that the decision-making power rests in local hands does not cause these problems. According to the study, the difficulty is that the criteria for decision-making are exclusively local.

Complaints are also heard that zoning cannot effectively implement a comprehensive plan. The zoning process demands that a particular use for each parcel of land be prescribed at the time a zoning ordinance is adopted. This method of planning does not allow for meeting community needs as they arise. Trying to accommodate public needs on a case-by-case basis when operating from long-term established assumptions inevitably allows for unplanned development. And, when provision for change has been made, critics contend that the comprehensive plan upon which the program is based has been amended so many times that no logical relationship exists between the plan and the ordinance. In short, zoning ordinances are often based on no plan at all.

One of the most cogent arguments expressed against present-day zoning practices is that they consist of a series of prohibitions rather than a well considered and comprehensive development plan. One respondent in the Zoning Laws Study Commission survey said, "Planning should be related to the overall physical, social and economic environment, not just legal precedent."

Those with more esthetic concerns want stronger measures to protect critical environmental areas and historic sites and provide for green spaces in development areas. Critics of this persuasion believe that land use should be based upon the physical capacity of the land to support development. Environmentalists point to delicate land in the Florida Everglades that cannot support extensive development. Recent evidence shows that construction robs the marshy area of its natural watershed, and the ecosystem is changing with the dryer environment. No one knows what rippling effects this will have on the entire area. When homes were built on unstable land in California, mudslides caused untold financial loss. And more recently, Florida residents have seen their homes disappear into underground sinkholes. Some have suggested that a form of environmental impact analysis be done on land before any development is allowed.

What have states done?

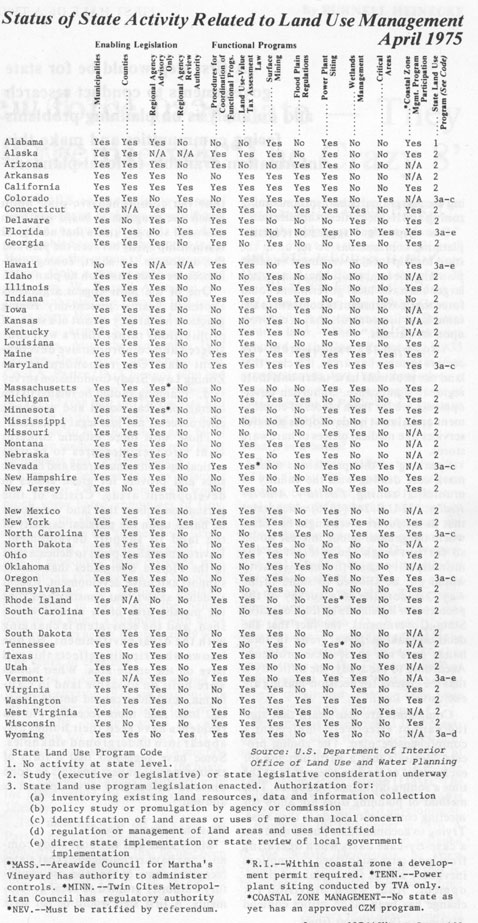

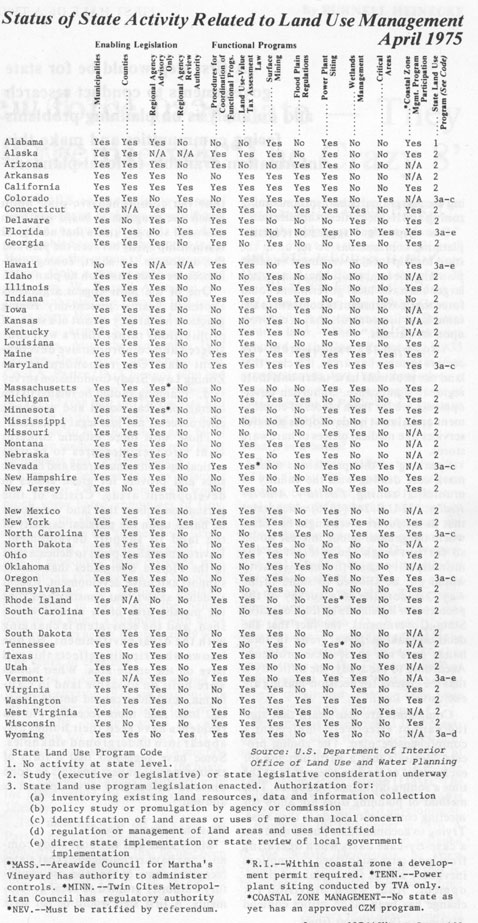

Many state and national study commissions have recommended that states recapture some of the land use regulatory authority granted to local governments. A first step would be for state governments to conduct research and do analysis on planning problems facing communities and make this information available to local planners. Other states have set statewide goals and policies that local planners must incorporate into their comprehensive plans. Still others have set specific regulations that must be met on a local or statewide basis. (See chart for overview of other states' land use controls.)

Vermont land use legislation, passed in 1970, includes a provision that requires state review if a development for commercial or industrial purposes involves more than 10 acres of land or a housing development of more than 10 units within a five-mile radius. The law also provides for discontinuance of scattered development along main highways and away from community centers because it causes "increasing government expense and loss of agricultural land."

Question of rights

Hawaii legislation, passed in 1961, created a seven-member state land use commission to delineate and oversee planning in four land use districts in the state: urban, rural, agricultural and conservation — subject to review every five years. Local governments can zone within the districts, except for the conservation district. Anyone wishing to use land not in accordance with a particular classification must petition the county planning commission or local zoning board of appeals.

Many are concerned that such laws calling for more centralized authority over land use are another sign of the end of private property rights and the American private enterprise system. Proponents respond that with an ever-growing population, considerations of public rights demand a much broader interpretation than when land was abundant. Preserving the quality of life may mean that many individual rights will be restricted by public concerns There is always the question of whose private property rights are to be protected. Land use laws may restrict oral least reassess commercial and residential development, but they may better protect the private landowner and farmer from pressures to sell to developers.

Next month: A discussion of land use legislation in Illinois' 79th General Assembly.

20 / January 1976 / Illinois Issues