By BURNELL HEINECKE

Editor of Heinecke

News Service, based in the state capital,

he formerly served 10 years as bureau

chief there for the Chicago Sun-Times.

It cost Illinois millions to learn the need

for an independent postaudit agency

After the state's fiscal watchdog turned out to be

a fox in the hen house, a three-man committee

turned in a report that led to the creation

of the Legislative Audit Commission, an agency

which chalked up savings of $10 million

THE YEAR was 1956. Illinoisans were

reeling at the magnitude of the scandal.

State Auditor of Public Accounts Orville E. Hodge, who was presumed to

be the public watchdog on fiscal matters, turned out to be a fox in the chicken

house. Hodge had stolen $ 1.5 million of

state funds and misused at least another

$1 million to his benefit.

The three-man panel which investigated the scandal concluded:

"The refrain 'Who takes care of the

caretaker's daughter while the caretaker's daughter is taking care' has rung

painfully upon the eardrums and seared

the minds of the citizens of Illinois since

June of this year when the sensational

and almost unbelievable news first began to break in the public press" (Jenner-Morey-Rendleman Report and

Recommendations to the Illinois Budgetary Commission, Dec. 4, 1956). As a

result of the scandal a number of major

reforms were recommended in the report.

One of the first reforms was the

creation in July 1957 of the Legislative

Audit Commission (LAC) — a bipartisan body assigned by the legislature to

review audits of the state agencies under

one or more of the elected executive

officials. Prior to 1956, audits were

commissioned by the state auditor of

public accounts, but then the audits

were turned over to the agencies audited, filed with the Budgetary Commission, and that was the end of it. But the

auditor never commissioned an audit of

his own office. Only when funds were

reduced to an alarmingly low level by

the siphoning off of office appropriations, did it become suspicious to inquiring reporter George Thiem.

Another of the crucial reforms recommended in 1956 was the separation of

the check-writing function of the auditor of public accounts from the post-audit (reviewing) function. The latter

was to be performed by an auditor

general. He was to be appointed by the

legislative branch, but he was an

appointee of the governor until 1973

after the new Illinois Constitution made

the change, and the legislature implemented the provision.

From its creation in 1957 to the

present, the LAC has proved itself to be

the watchdog agency envisioned by the

three investigators who recommended

its creation in their 1956 report. The

three investigators were Albert E. Jenner, Jr., past president of the Illinois

Bar Association; the late Lloyd Morey,

who was then former president and

comptroller of the University of Illinois; and the late John S. Rendleman, who

was at that time legal counsel to

Southern Illinois University. They

shared the responsibility of probing not

only the magnitude of Hodge's crime,

but also the weaknesses in the governmental structure that made it so easy for

dishonest individuals to pluck and loot

funds under their control. The men

wrote their recommendations in a

report to the Illinois Budgetary Commission, but were teamed as investigators by executive appointment. Morey was appointed by Gov. William G. Stratton to replace Hodge as state auditor in mid - 1956. Atty. Gen. Latham

Castle named Jenner and Rendleman as special assistant attorneys general to

join Morey in the overall probe.

One of the major findings of the

Morey-Jenner-Rendleman report was

the virtually unchecked autonomy of

operations that existed for elected

officials such as Hodge. Time and again

the report strongly supported the concept of accountability of all departments, agencies and elected officials to

the legislature.

Agencies and departments should

have the responsibility for pre-audit of

vouchers going to the auditor of public

accounts for payment, the panel said,

but then the postaudit function should

rest with a legislative panel. The philosophy of checks and balances inherent in

our form of separate branches of

government, the report suggested,

mandates legislative overview of expenditures of appropriations that have

been determined by the peoples' representatives — the legislators.

Former Sen. W. Russell Arrington

(R., Evanston), who served on the LAC

from its beginning in 1957 through 1972

(the year when he was incapacitated by a

stroke), recently recalled the obstacles

to the appointment of a legislative auditor general. Arrington noted that

the creation of the LAC itself was no

problem, but that Gov. Stratton and a

majority of the legislators balked at the

idea of appointment of the auditor

general by the legislature. Arrington

recalled that he and the late Paul

Powell, then the driving force on the

Democratic side, finally agreed that

Stratton should have the power of

22 / June 1976 / Illinois Issues

appointment; but that once appointed, the

auditor general would be responsible

to and report to the LAC and not the

governor.

Despite the fact that the manner of

selecting the LAC members assured

Republicans overwhelming control at

the outset and for many years thereafter,

Arrington noted that Powell wholeheartedly supported the proposed

legislation and helped secure its enactment.

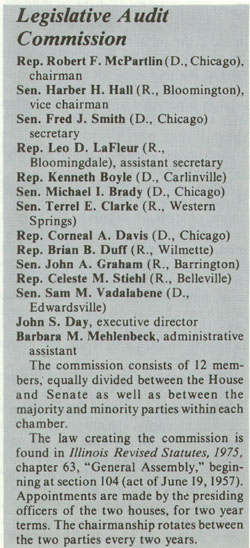

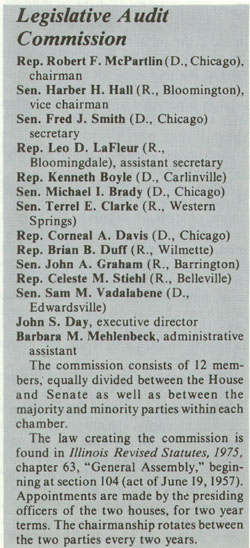

At present, the commission has a

policy of rotating the chairmanship

between Democrats and Republicans,

and membership is evenly divided

between the two parties.

Describing the original apprehensions, Arrington noted: "Everyone

thought they'd hate the commission,

that it would be a spy. But I think we

demonstrated from the first that we

meant business, that we were not going

to be political, and they came to respect

it perhaps more than any other commission. Our whole approach was not to

hurt people, but to help them in their

agencies, in seeing that they stayed in

line with what they were supposed to be

doing." As one veteran commission

member has observed, the feeling that

the commission must justify its existence has passed.

Arrington served as LAC chairman

for many years, even as he worked his

way up to the powerful position of

president pro tempore of the Senate.

One of the men who served as executive director of LAC in the Arrington

years observed that Arrington's demeanor as a member and chairman of

the LAC was completely opposite his

role as leader of the Senate: "Some of

the commission members from the

House, who had heard of Arrington as a

tyrannical, tough dictator on the Senate

floor, were absolutely astounded when

they worked with him on the commission — to find that he approached his

commission responsibility as an equal

with the others — completely willing to

abide by the wishes and the desire of the

majority without dictating policy." Reporters observed the same paradox: Arrington was absolutely assertive on

the Senate floor, but was unwilling to

suggest "what the guys will want to do"

on an audit commission matter.

Because of the Hodge scandal, much

of the original thrust of the LAC's

overview was directed at the fiscal

integrity of the agencies or departments under audit. Since the State of Illinois

was then on biennial budgeting schedules, by the time the audit of a department was completed and reviewed by

the LAC, it was not unusual for another

biennium to be drawing to a close.

In practice, as an audit report was

received from private auditing firms by

the auditor general, the report would

then go to the department covered by an

audit for the department's comment on

the findings. In recent years, the auditors have become increasingly responsive to pinpointing problems for both

the auditor general and the commission.

Part of the pressure for pinpointing

specific problems came from the press as

it uncovered practices and procedures in

various offices which violated statutes

such as the new Purchasing Act enacted

after the Hodge scandal. Veteran LAC

members such as Arrington and Sen.

Fred J. Smith (D., Chicago) and former

Sen. Robert W. Cherry (D., Chicago)

would question the auditors who had

not reported what the press had pointed out.

|

Something else was in play. It was

what John Day, the present executive

director for LAC and former staff

member of the Senate Democratic

Appropriations Committee, likes to call

"the power of coercion."

When Arrington or Cherry found

some director or head of an agency

hedging on a request to meet an auditor's recommendation for change or

corrective steps, Arrington's face would

turn red; he would puff heavily on his

cigar, generating a mushroom cloud of

smoke over his head. Then he would

curtly remind the director to be back

next month with better answers or there

might be "hell to pay" when his appropriations bill next came before the Senate.

Men such as Dick Viar, who served

more than 15 years as executive director

for the commission, as well as Day and

Arrington, emphasize that the function

of the commission is not investigatory.

In fact. Day stresses, if the commission

or the auditors find something illegal

that could lead to prosecution, the

matter is promptly turned over to proper authorities.

One of the items in the audit commission's reports that Arrington always

pointed to with pride was each report's

concluding summary of savings achieved for the taxpayers as a result of

commission proceedings. When Arrington stepped down in 1972 that sum

stood at $10 million. The staff has not

updated the running total in recent years, although Arrington wishes they would.

With Robert Cronson in office as the

first legislatively appointed auditor general, there has been a step-up in program

audits and other methods designed to

test whether departments are properly

carrying out their assigned missions.

Some of the clashes the commission

has had with Gov. Dan Walker's legal

counsel and several of his directors,

Arrington believes, were skirmishes

based on the governor's misunderstanding of the overall role of the commission.

Cronson noted that after due consideration, Walker's legal counsel

William Goldberg, backed off from a

directive to agency heads not to supply

material to the auditor general until

Goldberg had approved the material.

Perhaps, someone suggested, Goldberg

had gone back to read the Morey-Jenner-Rendleman report.

|

June 1976 / Illinois Issues / 23