THERE is an old saying that no city manager was ever fired for lack of competence. This means that the reason is always political in nature. This statement is true only in the most superficial way. Dismissals are for a variety of reasons and only a few are purely political. Council dissatisfaction with managers almost always involves technical expertise in someways, because technical expertise must include a modicum of political judgment. In most cases, conflict between a manager and council represents a breakdown of the manager's image of technical competence. The most technically competent managers are the most successful at what observers call "politics" as well as the purely professional parts of their jobs.

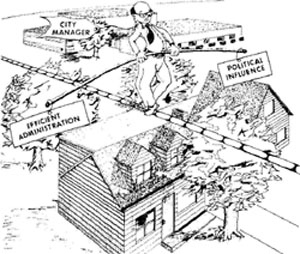

Caught between the standards of administrative efficiency and the pressure from local interest groups, Illinois' 96 city managers must demonstrate both technical expertise and political shrewdness to do their job well — and to keep it. The fact that, nationally, the average city manager stays only three to five years in a city indicates the demands of the job.

Spectrum of political styles

The city manager form of government

is in use in Illinois cities ranging in size

from Peoria's 125,000 residents to

several cities under 5,000. Approximately

80 per cent of manager cities are

in the greater Chicago area, and most

are suburban municipalities. About

one-quarter became manager cities after

1970 {see August 1975, pp. 231-233)

with most of the others adopting the

plan since 1950. The spectrum of

political styles in these cities is broad,

and managerial roles include "ho-hum"

municipal caretakers, technically expert

administrative "engineers,"

political in-fighters, and combinations of all these

types. Some managers have been in the

same city for over 20 years, while tenure

in cities with more controversy is much

shorter. Sometimes managers leave

because they are forced out, but more

often they move to other cities for

professional advancement.

Administration and politics

The city manager is expected to

operate the municipality efficiently and

to exercise control over all city departments.

Most managers consider themselves

"professionals" in municipal

management and have considerable

training, often a master's degree in

public management and experience in

smaller cities. Although they call themselves

professionals, their discipline is

difficult to define exactly. There is no

truly "scientific" way to operate a

municipality because local government

reflects the ideas of democratic control

just as much as it does the canons of

administrative efficiency. The city

council, as the elected representatives of

the people, has the last word (some

managers would say the "only" word)

on municipal policies, and the manager,

in effect, works for the council. This

means that even the most clearly defined

questions of administration are often

infused with purely political considerations.

The good city manager is one who

understands the proportions of the mix.

Most managers are adept at such

analyses, and the most thoughtful are

fully aware that "grass roots control" by

the council must take precedence over

administrative efficiency when the two

clash.

The job, therefore, requires varying blends of managerial skill and political savvy. The latter is most important when the manager feels he must introduce policy questions which the council wishes to sidestep. An example of such a question is an employee pay and classi-

July 1976/ Illinois Issues/3

Most managers try to be very, very sure of their ground when they are dealing with a police chief

fication plan which equalizes the varying salaries among city employees, but which the council suspects may result in some valued "old timers" on the staff getting less money compared to other employees or classes. The manager will be careful to present the plan at the moment when the council is most receptive (for example, after employee complaints about inequities). He will probably make arrangements for "old timer" longevity pay. If the council accepts such a plan, it is as much a tribute to the manager's political shrewdness as to the technical merits of the plan.

This kind of situation places a premium on the manager's political sagacity, but most managers, committed to the best personnel practice possible, do not call the tactical and strategic considerations involved "political." Rather, they explain such considerations under the heading of "technical expertise" — in other words, a sense of timing and judgment. To the manager, "technical expertise" includes more than budgeting systems, street paving practice or personnel plans. It also includes the ability to know when a proposal is ripe for presentation to the council, which kinds of programs are simply inappropriate for the city, and the capacity to gauge the limits of purely "professional" ideas.

Expectations of council

Technical issues usually have political

ramifications, and the wise manager

does not feel that considering them

indicates any weakness in his

professional judgment. The manager,

however, must understand what the council

or board expects of him. Some cities

want a straightforward manager who

presents technically correct solutions

which they accept as a matter of course.

Generally, these cities are dominated by

business or commercial interests. Some

cities also want this type of manager but

feel free to reject his advice in order to

demonstrate who is boss. This is fine if

the understanding between the council

and the manager allows for such a

procedure. Some councils become

distressed and even hostile if the manager offers professional

recommendations which are not politically palatable.

The expectation is that the manager will

use some political calculus to solve a

community's technical problems.

Not surprisingly, some councils want a manager who is all of the above. In such cases, the manager's job is extraordinarily difficult. Those managers who have managed to survive and thrive — in such situations have generally formulated some unwritten rules for different aspects of the job. What follows is my summary of these rules of thumb.

Involvement with policy questions

The law and a substantial amount of

public opinion hold that managers

merely execute the law. Although this is

an oversimplification, managers believe

that presenting such an image is good

professional practice; it is also politically

prudent. If the manager assumes a

role in policy leadership, whether or not

he means to, he is responsible for the

failure or success of the program. The

general public need not be aware of this

posture; certain influential groups may

associate him with the policy. Sometimes

a new council, victorious over the

incumbents, may associate the manager

with the policies of previous council-men.

This may have been the case in Palatine, where City Manager Bert Braun became vulnerable for several reasons. In 1973, the newly elected Republican party ousted the Village Independent party. They also associated Manager Braun with the previous Village Board majority. At the same time. Manager Braun publicly defended Palatine Police Chief Robert Centner, who had resigned under pressure from the Republican majority. Braun was perceived by the new council as partial to a defeated council majority and an unpopular police chief. Shortly thereafter, he too resigned and became manager of Woodridge.

The same situation occurred in DeKalb some four years earlier when a four-member "economy bloc" gained a majority on the council. The majority fought with the pro-spending minority, and City Manager Ralph Precious was drawn into the struggle over budget priorities, salary increases for department heads and a new airport. Public statements were made by members of the four-member majority attacking city spending and asking for the manager's resignation. Precious turned in his resignation, and the "economy bloc, "by a 4 to 3 vote, accepted it. The DeKalb struggle is notable because it did represent an ideological struggle which the manager could not avoid.

These cases are unusual; normally managers try not to make public statements which are at odds with a dominant council view. They also try to avoid being associated with one or another bloc. Most prefer a closed session for frank exchanges on personnel matters rather than an open conflict. (Closed sessions can be legally held on personnel and property acquisition matters under Illinois law.) At, times, of course, managers do become associated with a minority bloc and can not convince the dominant majority of their neutrality.

Dealing carefully with department heads

Managers in Illinois are responsible

for appointing and dismissing

department heads, many of whom have spent

many more years in the community than

the manager. Disciplining or firing such

an individual, who may have many

friends in the community, may displease

council-men. Conversely, it can be

dangerous to defend such department

heads when the .council is displeased

with them. Professional managers try to

approach these questions from the view

of what seems best for the municipal

organization and the city as a whole.

Usually, the council is apprised in a

personnel session of recommended

actions involving a department head

before any action is taken. This is both a

courtesy to council-men, who have a

right to "hear about it first, "and an

opportunity for the manager to obtain

feedback from the council-men before

there is a vote in open session.

Problem of police chief

Of all department heads, the police

chief normally poses most problems for

a city manager. First, managers often

have less expertise in police matters than

in any other municipal function.

Compounding this lack of expertise is the

4/ July 1976/ Illinois Issues

fact that police matters are often confidential, with the manager often one of the last to know. Also, in Illinois cities, the mayor is normally the liquor commissioner, and thus is privy to more information about police or vice matters than the manager. Finally, the nature of police matters lends itself to rumor, gossip and acts which many parties may have reason to conceal. This is not a situation in which the managers professional expertise is persuasive, particularly when the police chief is often a local person with both substantial community support and possession of information embarrassing to many people. In short, most managers try to be very, very sure of their ground when dealing with a police chief. In Elgin, City Manager Robert Brunton was forced out of office in 1972 partly because of disagreements between himself. Police Chief James Hansen and a new council majority, one member of which was an ex-policeman. The facts are unclear, but the police chiefs resignation and the conduct of the police department was a major factor in Brunton's departure.

Sometimes the situation is simply impossible. In Woodridge, City Manager Kenneth Carmignani resigned (to become manager of Oak Brook) two weeks after the election of Joel Kagann as village president. Kagann had been fired by Carmignani as police chief of Woodridge just prior to the election and was then elected village president in a write-in campaign. Kagann and the new board then hired Bert Braun (formerly of Palatine) as manager. It is not clear if Braun's support of Police Chief Centner in Palatine was a factor in his appointment. It is clear, however, that managers generally treat police chiefs with extreme caution. The above examples show why.

Public relations

The manager's role in public relations

is complex, with substantial variation

from city to city. Relations with news

media is one element of the public

relations role. Most managers learn how

to deal effectively with the media,

although their styles vary greatly. Some

maximize their contacts, feeding as

much information to the media as

possible. Others attempt to stay out of

the spotlight, leaving comments to the

mayor or council-men. Managers feel

that credit or blame for policy matters

belongs to the mayor and the council,

since the municipality's legislative body

is free to reject or accept a city manager's

recommendations. Managers accept the

responsibility for the way that policy is

carried out. However, this division of

responsibility breaks down from time to

time. One reason for this breakdown is

that the manager, as the appointed

expert, is vulnerable to media demands

that information be revealed and explained.

He has the job of explaining

city policy in all its complexity and/or

contradictions.

Responding to media

The manager is also available to the

media and public during working hours.

Often he is pressured into speaking for a

mute council majority, or at least to

"explain" an issue such as dismissal of a

popular department head or a new

personnel policy. Speaking out is risky,

since he may say something which is

displeasing to the council. The manager

may say that any comment has to come

from the council since it makes legislative

policy, but the council may resent

this transfer of pressure. Unhappily for

the manager, he may lose council

support whether he attempts to explain

policy or remains silent.

Personnel actions, usually discussed in closed sessions, are the commonest type of decisions which can be defended by "no comment." Often the city manager is the victim of these kinds of adverse decisions, which the council may refuse to formally discuss, or justify with generalizations such as, "It was for the good of the city." This was the case in Elgin, when Manager Brunton's forced resignation at a closed personnel session was accepted but never explained or defended by the council majority despite heavy pressure from the local paper and many supports of the manager plan. The paper offered space for an explanation, but the council majority refused to speak, other than noting that "10 years was long enough," or Mayor William Rauschenberger's indication that city managers stay only about five years in one city.

Socializing with citizens

Relations with citizens comprise the

other half of the manager's public

relations job. Most managers, as

community leaders, attempt to integrate

themselves into the social life of the

community through church membership,

business clubs such as Rotary and

Kiwanis, and various social groups. In

this way they feel that they can be

accessible to citizens and obtain a better

sense of the community. Some managers,

who may be equally effective, feel

July 1976/ Illinois Issues / 5

City managers are a highly mobile group. Some leave involuntarily; others seek professional growth and development

that immersion in the social life of the community may inadvertently involve them in potential conflicts or make them vulnerable to charges of favoritism. The pattern of citizen contacts and group membership varies substantially from city to city. The primary determinant of group membership, in most cases, is probably the nature of the community and the expectations of the citizenry and the council rather than the individual preference of the manager.

Mobility of managers

City managers are very mobile professionally. While this mobility

generally benefits municipal government,

as we will see, bringing in a new manager

every five years or so occasionally

breeds considerable resentment at the

manager system generally. Managers, it

is alleged, are "carpetbaggers." They

stay for a while, then leave. A local

person, some complain, would stay and

finish the job.

It is true that at times managers have left cities in the midst of difficulties, for apparently flimsy reasons that appear selfish. However, there are a number of good reasons for managerial mobility. A chief advantage is that some managers leave because they are asked to or can see the handwriting on the wall. This underlines the flexibility of the manager plan, a system that allows for executive changes without waiting for a term to expire. It also emphasizes the democratic control of the council, which is free to dismiss the manager at any time for any reasons it wishes.

Managers also feel that serving different types of cities contributes to their professional development. Given the nature of their job, with its risks and responsibilities, and considering the fickle nature of councils, mobility is probably no greater than should be expected. The costs of turnover are matched by the benefits of experiences in a variety of cities. With the added benefits of absolute democratic control by the council, the net result is probably a gain. At least, most managers say so.

Success stories

The examples, so far, have pointed

out the difficulties managers have in

surviving political conflict. To some

extent it has been a one-sided picture,

for most managers are able to balance

political considerations with the need

for high levels of technical competence.

Many Illinois cities have had long and

successful managerial tenures. Some,

like Glencoe and Glenview, are

relatively quiet suburbs where conflict is

rare. But there are other communities

with turbulent politics, where managers

have had lengthy stays or have been able

to accomplish a great deal before

moving on voluntarily. Robert Brunton

was manager in Elgin, a city where local

politics has been very lively, for 10 years,

and was succeeded by another

competent manager when he left. Elgin is a case

where managers have been able to

perform in a highly competent manner

in a highly charged political

environment. A similar case is Evanston, an

intensely political city that has still had a

series of highly respected managers.

Arlington Heights has had the same

manager since the late 1950's, despite

explosive growth and change. Elmhurst

has had the same manager for many

years.

Alternative forms

Other cities, such as Oak Lawn, have

had a fairly rapid turnover of managers

but have still chosen to continue this

form of government. This is because, in

most cases, the alternatives are not very

promising. The commission form of

government often mixes administrative

and legislative functions. The mayor/

council form often works effectively,

particularly in cities such as Des Plaines,

where Mayor Herbert Behrel

administers the city on a full-time basis, but the

city still faces the inevitable problem of

electing an administrator. This simply

does not work in most cases, and larger

communities often turn to the manager

plan and stay with it even with a

turnover of managers, because it does

maintain democratic controls and

normally assures technical

competence. ž

6/ July 1976/ Illinois Issues