By MARK HEYMAN

A faculty member of Sangamon State

University, Springfield, he is author of

Simulation Games for Classroom, Phi Delta

Kappa Educational Foundation, 1975.

College grades go up, but achievement test scores go down

A mystery in our schools

Test scores for students from third grade on have declined for the last 10 years, while college grades have never been so high or meant so little. Many reasons are given by parents and educators. It might be that both schools and tests have not caught up with the real world

SCORES ON educational achievement tests have been declining for the past 10 years, and that's definitely not news. But the mystery behind the trend has not been solved.

Dr. Lucky Abernathy of the Chicago office of the College Entrance Examination Board says that increasing numbers of people are asking school officials about the causes for the decline and what can be done about it. They want more than explanations; they want action, such as changes in the curriculum. But, as Dr. Abernathy notes, while many hypotheses have been offered about the problem, and while most seem reasonable, nobody has yet been able to pinpoint the reasons for the decline. Justifiably, the man in the street is perplexed. Dozens of reasons have been offered, from cutbacks in the space program and TV to the increased use of drugs. Most of the diagnoses, however, are centered on students and why they are scoring lower than earlier generations. Few analyses question the accuracy of the tests themselves.

An expert on testing. Dr. Donald Beggs, professor of guidance and educational psychology and associate dean for graduate studies and research at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, states that, in the controversy swirling about the test scores, not enough people are asking if the tests are assessing what we want taught in schools. Dr. Beggs notes that tests emphasize information and specific facts, but we have increasingly asked schools to emphasize the integration of ideas and concepts, decision-making skills and ways to help young people better understand themselves, all objectives not readily assessed by tests. Dr. Beggs believes that this may be a time for the reexamination of our expectations of schools. Another factor that Dr. Beggs believes should be considered is the declining importance of test scores for admission to college, since many now have open admissions.

The person who can explain this national whodunit has yet to come forward. But, there are some facts behind the mystery which are indisputable. First of all, the scores of widely used achievement tests, with a few exceptions, have been declining for about 10 years. Some of these tests are:

• American College Testing Program (ACT) — English, mathematics, social studies and natural science for college- bound seniors;

• Comprehensive Tests of Basic Skills — mathematics, reading and language skills for grades 2 through 10;

• Scholastic Aptitude Tests (SAT) — verbal and mathematical abilities for college-bound seniors;

• Iowa Tests of Basic Skills — reading, language, vocabulary, math and work study skills for grades 1 through 8;

• Iowa Tests of Educational Develop-

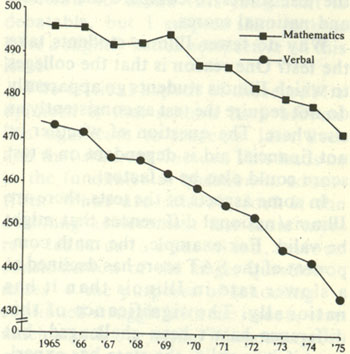

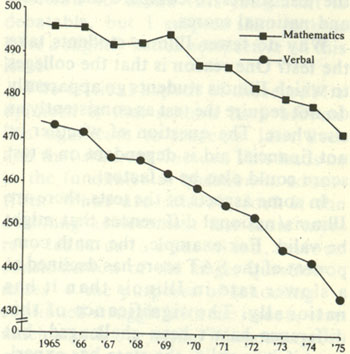

SAT scores nationwide, 1965-1975

*Source: Annegret Harnischfeger and David E. Wiley, Achievement Test Score Decline: Do We Need To Worry? (Chicago: CEMREL, Inc., December, 1975)

January 1977 / Illinois Issues / 21

Both grade inflation and declining test scores are linked to causes that reflect basic cultural shifts

ment — expression, quantitative thinking, social studies, natural sciences, literature, vocabulary and use of sources for grades 9 through 12.

For students above the third grade, the average national scores on these tests have declined steadily since the mid-1960's; an exception is the ACT science scores, which have remained steady. Some declines are much more severe than others, but the general pattern is indisputable: it's down.

How does Illinois compare?

To compare Illinois students to the

national average, SAT scores provide a

good example. SAT figures are better

for Illinois students than the national

average, but the significance of the

difference is questionable because the

percentage of Illinois students who take

the test is less than the percentage

nationally. One-third of students nationally take the SAT, but only about 16

per cent of Illinois students are tested.

(Other states range from 3 to 65 per cent

of eligible students taking the SAT.)

Because of this difference in percentage

of test takers, it is not reasonable to use

the test scores to compare the Illinois

and national scores.

Why do fewer Illinois students take the test? One reason is that the colleges to which Illinois students go apparently do not require the test as consistently as elsewhere. The question of whether or not financial aid is dependent on a test score could also be a factor.

In some aspects of the tests, there are Illinois/ national differences that might be valid. For example, the math component of the SAT score has declined at a slower rate in Illinois than it has nationally. The significance of this difference hasn't been challenged, but even if it is valid, the state has experienced a decline, which is just what the nationwide problem is anyway.

At the same time that achievement test scores have been declining, there has been a steady upswing in grades, especially in colleges. Complicating any fair appraisal of grade inflation is the great variety in the forms of grading, such as letter grades, numbers, pass/ fail, pass/ no record and written evaluations only. Furthermore, it is clear that when students have a choice of instructors or a choice of grading systems (sometimes within the same class), the compiling of statistics does not always result in meaningful data. However, one 10-year study by the American College Testing Program revealed a steady increase in the grade average for all courses taken by students in the first semester in college.

When did it begin?

Grade inflation has resulted in larger

numbers of students graduating from

college with honors. One reaction has

been a movement to reintroduce the

recording of course failures on a student's record. Also, graduate schools

have complained that some undergraduate transcripts are not useful for

admissions decisions. Grade inflation

was first noted during the Viet Nam

War, when good grades could keep a

student out of the draft, at least temporarily. Also, in the 1960's, the rise of

students' rights movements and anti-elitist sentiments influenced the attitudes of teachers and administrators

towards grading people. Some educational analysts believe that grade inflation and lower test scores are linked and

that both can be traced to a decline in

the level of teaching.

Who is to blame?

As noted earlier, many reasons have

been offered for declining test scores; some of these are contradictory. The

following is a list of the most frequently

offered explanations for the decline:

• Achievement tests no longer measure what is important today.

• Cutback of the space program deemphasized science and mathematics.

• Discipline problems leave teachers little time and energy to teach.

• Dropout prevention programs, open admissions, and other efforts that keep youth in school longer, have increased the proportion of the less capable students.

• Five to six hours of television a day leaves no time for homework and has caused a shift from verbal literacy to visual literacy.

• Increase in broken homes has weakened parental influence.

• Increased leniency in grading has resulted in less rigor in teaching.

• Increased use of alcohol and other drugs has impaired learning.

• Schools have been given too many tasks beyond their basic function.

• There has been a shift in emphasis from factual learning to personality development.

• Students are more job-oriented and less academically oriented.

• Students have more course choices and they don't choose science, math, and writing courses.

• Teacher training and in-service training are inadequate.

• Teachers are increasingly interested in their pay and working conditions and less devoted to teaching.

• Too much money in education is spent on "frills," sports, and extracurricular activities. 1

These reasons place the responsibility either on society or on schools. If the responsibility is society's, is it because of television, drugs, family breakdown and permissiveness — or some combination of these?

Do big families cause low test scores?

If the responsibility is the schools', is

it because they have wandered from

basics or because teachers are more

interested in their pay than in teaching?

Or does the problem stem from increased retention filling schools with

students of lesser abilities — or some

combination of these explanations?

One unusual explanation is the Zajonc/ Markus theory (see Psychology Today, April 1976). At the University of Michigan, psychologist Robert Zajonc and political scientist Gregory Markus are convinced that declining test scores are the result of the impact of demographic trends on intelligence, a major factor in achievement tests. Zajonc/ Markus believe that intelligence is influenced by the size of the family and by the spacing of children. Smaller families have brighter kids, as do families with more widely spaced births. They reason that these families maintain a better intellectual environment. Zajonc/ Markus say that we have nothing to worry about. Demographic trends now underway are resulting in smaller families and more years between

22 / January 1977 / Illinois Issues

births in the average family. Consequently, they conclude that test scores will naturally rise around 1980.

Not many are as sure of their explanations as Zajonc/ Markus. More research is needed before we will feel entirely comfortable about the problem of declining test scores. Meanwhile I offer here what I believe is a reasonable package of reasons drawn from the many that have been offered. My package does not result in easy solutions but it may help to explain the mystery.

How great is impact of TV?

My package includes television, the

testing tradition and changing values.

Television is very important, not only

for students, but also for adults. In my

view, we have yet to fully understand the

changes that television has made in

society during the past 25 years. Media

theorist Marshall McLuhan made a

start several years ago, but no one has

followed his lead or significantly modified his challenging observations.

The sheer amount of time Americans spend watching television is astounding. For preschool children, three to five hours daily is normal. Before a child enters school, 4,000 hours have been logged on the tube. Thereafter, school doesn't have a chance to catch up because TV is an all-year activity. The average student spends under 1,000 hours in school annually, but averages 1,300 hours watching television. Result: At graduation from high school, the typical youth has devoted 22,000 hours to television, and 11,000 hours to schooling. Obviously television has encouraged a shift from the written word to the spoken word and to the image. We read much about the decline in literacy. Television's influence on society in the last 25 years perhaps surpasses the initial impact of the printing press. But the testing tradition has not changed significantly since the advent of television. Testing is still based on two traditional ideas that some people now question: (1) the enduring value of the printed word and (2) the belief that a test is able to measure something important about humans.

It is likely that the testing tradition has been even less adaptable to change than our school system. The schools try to be up-to-date, but the tests are trying to hold to academic values of the past. When students are given a choice of subjects, they frequently reject courses that belong to the academic tradition: history, English courses that involve writing, and traditional science and mathematics. They favor courses concerned with current public issues such as ecology, law and ethical questions, as well as private interests such as small engine repair, interpersonal relations and popular music — the types of subjects selected by many adults as well.

The "changing values" reason for the test score decline follows from the analysis of television and the testing tradition. The societal (and consequent school) shift from traditional academic subjects like history, English, science and math, is a response to basic value shifts. Though the downgrading of the written word must be deplored, who would not welcome the shift in basic values which elevates individual concerns and avoids easy standardization? Tests are in tension with this humanistic movement, which is supported by the various rights movements and the idea of cultural pluralism. No one can foresee how all these changes will work out, but the decline in test scores is not totally bad from this perspective.

Whether or not my package of reasons appears reasonable, the issue of declining scores might lead us to pay closer attention to what has been happening in the "real world." An analysis of what people think about schools in general may be of help. One of the questions in the 1973 Gallup Poll on education was, "How important are schools to one's future success — extremely important, fairly important, not too important?"

|

|

Extremely important |

Fairly important |

Not too important or No Opinion |

|

|

National totals |

|

|

|

|

|

By age groups |

|

|

||

|

18-20 |

|

|

|

|

|

21-29 |

|

|

|

|

|

30-49 |

|

|

|

|

|

50 and older |

|

|

|

|

|

Public school |

|

|

||

|

parents |

|

|

|

|

|

No children |

|

|

||

|

in school |

|

|

|

|

|

Professional |

|

|

||

|

educators |

|

|

|

|

Note that the youngest respondents

(those between 18 and 20) see the least

connection between school and later

success. The older the respondent, the

stronger the belief in the importance of

education for later success. This can be interpreted either as a result of the

wisdom that accrues with age, or of

actual changes in the relationship

during the last 30 years. I favor the latter

explanation and believe that there has

been an increasing disparity between the

"real world" and school, at least since

World War II. Society has changed

substantially while schools have

changed minimally.

It is also significant that there are fewer professional educators in the "extremely important" category than there are parents of public school children (69 per cent v. 81 percent). The percentage for educators (69 per cent) falls between the percentages for the 18-20 (63 per cent) and the 21-29 (72 per cent) age categories, and this certainly cannot be due to the age of educators.

What does the public think?

A new question in the 1975 Galiup

Poll on education asked the public for

reasons for the declining achievement

test scores. One out of eight could offer

no reason; others gave a variety, as

expected, and they fell into five major

categories (because multiple answers

were accepted, the figures do not total

100 per cent). Reasons offered for

declining test scores:

Student's lack of interest/ motivation 29%

Lack of discipline in the home and school 28%

Poor curriculum (too easy, not enough emphasis on basics) 22%

Inadequate teachers, uninterested teachers 21%

Too many outside interests, including TV 8%

Miscellaneous (integration, overcrowding, drugs, etc.) 13%

Gallup reported that the general public stresses students' lack of interest more frequently than do professional educators. Which group is in a better position to make this judgment is debatable, but I suspect that parents have a slightly better perspective on this issue.

The critical aspect of these public opinions is that schools have become less significant to students' later lives and that students know it. This leads us to the fundamental question in education: What are schools for? If the declining achievement test score mystery leads us to a sustained, serious consideration of the larger question it raises — the purposes of schooling — continued struggle with the issue is very much worth our while. Without agreement on the purposes of schooling, there is not much point in worrying about such things as test scores.ž

January 1977 / Illinois Issues / 23