By CHARLES MINERT

A research associate for the Illinois

Legislative Council in Springfield, he

holds degrees in political science from

Park College, Kansas City, Mo., and the

University of Illinois, Chicago Circle

Campus.

No longer in existence after January 1979

*Personal property tax

|

UNLESS THE General Assembly acts

promptly, local governments throughout Illinois stand to lose as much as $585

million annually. Without these replacement revenues, many local governments

will face a financial crisis.

The personal property tax on individuals — but not businesses — was

abolished on January 1, 1971. For six

years the General Assembly has been on

notice that it must also abolish, by

January 1, 1979, the personal property

tax levied on corporations, partnerships, limited partnerships, joint ventures, professional associations, and

professional service corporations. Not

only does the Constitution require the

abolition of this tax on these businesses,

it also requires that the General Assembly replace the lost revenue with a new

tax on these businesses by the same 1979

date. So far, it has done neither.

Big job ahead for legislators

Undoubtedly, the General Assembly's delay in implementing this constitutional mandate is attributable to the

impending clash between the business

community and local governments.

Business interests will strenuously lobby

for legislation which will not increase

their tax burden and local governments

will press for legislation which will

assure an expanding tax base. In spite of

these tensions, the General Assembly

can no longer defer action. If they do,

local governments could go bankrupt.

The extent of the General Assembly's

task is revealed by a phrase by phrase

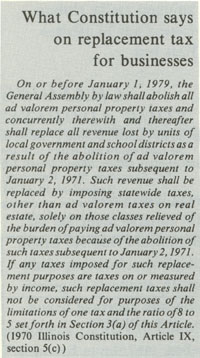

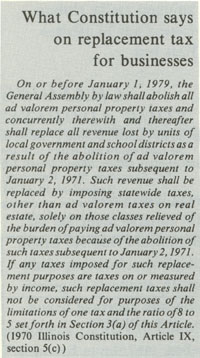

analysis of section 5(c) of Article IX in

the Constitution.

|

First, the General Assembly is required to abolish the personal property

tax and "... replace all revenue lost by

units of local government and school

districts as a result of the abolition of ad

valorem personal property taxes subsequent to January 2, 1971," that is, by

the property taxes on business to be

eliminated on January 1, 1979. Second,

all replacement revenues must come

from statewide taxes. Third, no replacement revenues can come from

taxes on real property. Fourth, replacement taxes may only be imposed

on those taxpayer classes relieved of

paying the personal property tax (businesses). Fifth, replacement taxes may be

based on the income of businesses,

corporations, et cetera.

The General Assembly's task is formidable. Determinations must be made

regarding the amount of personal

property tax collections and the replacement tax packages which will yield

an equal amount. Taxpayer classes must

be identified and evaluated in terms of

their capabilities to produce replacement revenues. Methods of allocating

replacement revenues and their impact

on local governments must be analyzed.

Finally, the General Assembly must

consider the ramifications if they fail to

enact replacement taxes. Given the

politically charged atmosphere in which

this issue will be discussed, it is important that some fiscal guidelines be

established so that replacement tax

packages that are proposed can be

evaluated properly.

Criteria for replacement taxes

In Replacement Revenue Sources, a

1973 study commissioned by the Illinois

State Chamber of Commerce, Dr. Robert Schoeplein suggests four basic

criteria: (1) the replacement taxes must

provide adequate revenues and be responsive to economic growth without

frequent rate changes; (2) the replacement taxes should fit into existing tax

collection and administrative machinery. Taxes which do not require increased

administrative costs to the state and the

taxpayer should be very carefully considered; (3) the replacement taxes must

18 / March 1977 / Illinois Issues

|

Mandated to replace revenues lost to school

districts and local governments with new taxes on

businesses, the General Assembly must decide

soon to change tax laws

or propose a constitutional referendum

be equitable so that taxpayers in the

same class should be subject to like taxes

and taxpayers of varying income and

wealth should be subject to different

tax burdens, according to their ability

to pay; (4) the replacement taxes must

be considered in the light of their economic impact on employment, migration and business investment.

One of the General Assembly's crucial

tasks is to accurately estimate the

amount of personal property tax revenues which must be replaced. Many

estimates will be made and the General

Assembly must pick and choose among

them. Recent data from the Illinois

Department of Local Government

Affairs indicates that 1974 statewide

personal property taxes, collectible in

1975, will total approximately $530

million. Assuming that about 15 per

cent of these taxes will not be collected,

the statewide personal property tax collections for 1975 will be about $450

million. Using this figure as a base and

assuming a 10 per cent annual increase

in collections for 1976, 1977, and 1978,

the statewide collections should total

about $585 million by January 1, 1979.

Burden on businesses

Any evaluation of taxpayer classes

must take into consideration that part of

section 5(c) which states that the

replacement burden must fall solely on

those taxpayers ". . . relieved of the

burden-of paying ad valorem personal

property taxes because of the abolition

of such taxes subsequent to January 2,

1971," that is, on businesses. Taxes on

personal property owned by individuals

were abolished by the adoption of

Article IX-A to the 1870 Illinois Constitution on November 3, 1970. The

effective date of this article was January

1, 1971. After this date and until January 1, 1979, only businesses pay

personal property taxes.

The Constitutional Convention anticipated the ratification of Article IX-A

by including section 5(b) in Article IX of

the 1970 Constitution. Section 5(b)

states that "[A]ny ad valorem personal

property tax abolished on or before the

effective date of this Constitution shall

not be reinstated." Consequently, only

personal property owned by corporations, partnerships, limited partnerships, joint ventures, professional

associations and professional service

corporations is currently subject to the

personal property tax. Any replacement

taxes will fall on these taxpayer classes.

In Replacement Revenue Sources,

the Illinois State Chamber of Commerce provides a detailed analysis of

taxpayer classes according to industry

groupings. The chamber's 1973 estimate

of the percentages of total corporation

|

|

Survey of statewide organizations on replacement tax issue

SPOKESMEN FOR 38 organizations

which have registered' lobbyists were asked

to comment on the personal property tax

replacement issue. Seven responses were

received. An increase in the income tax was

conceded to be the basic replacement source,

but five of the seven favored changing the

Constitution to retain the existing personal

property tax. A summary of replies follows:

David F. Ellsworth, state chairman,

Common Cause / Illinois, who emphasized

that the views expressed were his own, said

he favored amending the Constitution to

allow a personal to corporate income tax

ratio of 2:1 and raising corporate income

taxes to the level needed to replace the

existing tax. Alternatives to an increased

income tax might include a value-added tax

or retaining the existing tax, provided this is

tied to reform of the state administration of

the property tax.

Len Gardner, secretary, Illinois Agricultural Association, cited a resolution adopted by I.A.A. delegates at a meeting early in

December favoring a constitutional amendment to retain the existing personal property

tax.

Harold Dodd, president, Illinois Farmers

Union, favors amending the Constitution to

retain the tax. His alternative is an increased

income tax for replacing lost revenue.

Oscar A. Weil, legislative director, Illinois

Federation of Teachers, says, "Those who

supported the Constitution of 1970 assumed

the revenue from the income tax would be

used to lessen the tax burden on property

and to replace revenue lost by abolition of

the tax on personal property." He opposes

amending the Constitution to retain the

personal property tax, contending such a

move "would tend to erode the credibility of

state government." He favors amending the

Constitution to permit a graduated income

tax "not only to replace revenue lost from

elimination of the personal property tax, but

to allow reduction of the tax burden on nonincome producing real property."

William E. Stowe, Illinois State Chamber

of Commerce, favors a "balanced combination [of replacement taxes] to avoid massive

shifting of tax burden between groups,"

including an increased income tax as part of

the package. In opposition to amending the

Constitution to retain the existing tax, he

states, "This is a dangerous idea, advocated

by special interests."

Troy A. Kost, executive director. Township Officials of Illinois, favors retaining the

existing personal property tax by constitutional amendment. If this cannot be done,

Kost said, the state income tax should be

increased to replace lost tax revenues.

Urban Counties Council of Illinois

suggested a combination of sales, income

and public utility taxes as a replacement "to

insure that no shifting in the tax burden

occurs." Retention of the personal property

tax is seen as "the only solution" to insure

that no shifting occurs.

|

|

March 1977 / Illinois Issues / 19

Pressure is on the General Assembly

to get down to business and

avoid a fiscal and constitutional crisis in 1979

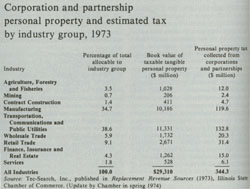

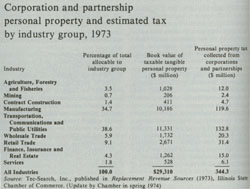

and partnership personal property of

each industry grouping, the book value

of taxable tangible personal property,

and the personal property tax collected

from corporations and partnerships is

illustrated in the table below.

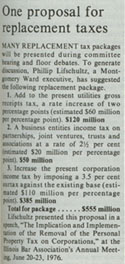

In considering particular replacement

tax packages, the General Assembly

must take note of the section 5(c)

directive requiring that replacement

taxes come from ". . . statewide taxes,

other than ad valorem taxes on real

estate." The reference to "statewide

taxes" implies that the Constitutional

Convention intended that replacement

revenues come from a package of two or

three taxes, rather than a single tax.

Section 5(c) also states that "[I]f any

taxes imposed for such replacement

purposes are taxes on or measured by

income, such replacement taxes shall

not be considered for purposes of the

limitations of one tax and the ratio of 8

to 5 set forth in Section 3(a) of this

Article." Thus, a surtax on income may

be considered as a viable replacement

alternative. In addition, it is important

to recognize that there is no constitutional requirement that taxpayer classes

currently subject to the personal property tax must pay exactly the same

amount under any replacement tax

alternative.

Allocation of new revenues

When considering methods for allocating replacement revenues, the General Assembly has two alternatives: direct dollar for dollar replacement or

replacement based on something other

than an absolute dollars lost criteria. In

either case, the General Assembly will

have to devise an allocation formula

which will insure an equitable distribution of the additional revenues the

replacement taxes will generate.

All of the foregoing presupposes that

the General Assembly will pass a replacement tax package. There is,

however, a possibility that the General

Assembly will not pass the necessary

legislation by January 1, 1979. The

opening sentence of section 5(c) states

that"[0]n or before January 1, 1979, the

General Assembly by law shall abolish

all ad valorem personal property taxes

and concurrently therewith and thereafter replace all revenue lost by units of

local government and school districts . . . ."

Dilemma for Supreme Court

There is some dispute regarding the

meaning and intent of this language.

The ramifications of this dispute were

dealt with by the Illinois Supreme Court

in Elk Grove Engineering v. Korzen.

Dicta in the majority opinion stated that

". . . the provisions of section 5(c)

constitute a mandate to the General

Assembly to abolish all ad valorem

taxes on personal property on or before January 1, 1979; that the provision is

not self-executing and legislation is both

contemplated and necessary to carry it

into effect; and that the provision does

not require that all such taxes be

abolished at one and the same time but

the General Assembly is under a continuing duty to effect their abolition on or

before January 1, 1979."

The dissent held that the personal

property tax is abolished on January 1,

1979, and the constitutional mandate

for replacement taxes cannot be judicially enforced.

|

If the taxes are not abolished and

replaced, a lawsuit will undoubtedly be

filed to determine the effect of section

5(c). If this happens, the Supreme Court

will face a serious dilemma. If it allows

the personal property tax to be collected

after January 1, 1979, section 5(c) is

meaningless. The imposition of another

deadline would be just as unenforceable

as the January 1,1979, date. If the court

refuses to allow the collection of the tax

after January 1, 1979, it is powerless to

enforce the General Assembly's constitutional mandate to replace lost revenues.

All personal property taxes paid after

January 1, 1979, will be protested and

held in escrow accounts until the court

decides on the legality of the personal

property tax. Recognizing the unenforceable nature of the replacement

mandate, the court could, nevertheless,

order that the protested taxes be held in

these accounts until the General Assembly

|

|

20 / March 1977 / Illinois Issues

|

enacts replacement taxes. The

pressure would then shift to the General

Assembly to deliver on its replacement

mandate. All of these possibilities

indicate that section 5(c) is seriously

flawed because it is not self-executing

and the replacement provisions are not

judicially enforceable.

The General Assembly could resolve

this dilemma by calling for a referendum

to amend section 5(c). Several alternatives are possible. First, the amendment

could change the date and buy more

time for General Assembly action.

Second, the amendment could change

the date and delete the replacement

provision, thereby averting an immediate fiscal crisis on the local governmental level. Third, the amendment

could delete the replacement provisions.

Senate Joint Resolutions 33 and 67 and

House Joint Resolution 27, introduced

in the 79th General Assembly, adopted

this alternative. Fourth, the amendment

could repeal section 5(c).

As January 1, 1979 approaches,

pressure to make a decision will increase. Delay and avoidance of this issue

are no longer possible if local governments are to have uninterrupted tax

revenues to support their services.

|

|

20 / March 1977 / Illinois Issues