Fiscal crisis:

When the state's budgetary pie isn't big enough to give a large piece to everyone

STATE MONEY is like a big pie. The endless, round budget charts all show it: where your tax money comes from and where it goes. And like a pie — banana cream, chocolate or blueberry — every-one wants a piece — a large piece. It doesn't take an economist to see a problem here, nor does it take a politician to figure out that the basis of politics is this struggle created by the size of the pie: how to divide limited reources peacefully among a voracious public.

On the level of state government, the governor prepares the budget each year, presenting it to the legislature as his reommendation for state spending. The legislature passes the appropriation bills, and it's very likely that legislators and the governor's political adversaries will poke their thumbs in the pie for a proverbial plumb to prove "what a good boy am I." But it's the governor who gets the credit or blame for the final product. If it's a mess, it's his mess. If everybody is full and fat and sassy, he goes on TV and smiles at them broadly and they smile back election time.

The one thing a governor cannot ignore is that the money pie is limited in size. The state government cannot spend more than it receives in tax revenues. In recent memory only one Illinois governor has been faced with such a shortage of state revenue that he found it necessary to increase taxes. In 1969 Gov. Richard B. Ogilvie asked the legislature to pass a new state income tax. He has since been lauded by experts for his courage and statesmanship in the creation of the state income tax. Unfortunately, the voters didn't agree, and Ogilvie found pie on his face when he sought reelection.

Since that political Waterloo, Illinois governors have been more cautious when confronted with similar "fiscal crises" — where spending threatened to outstrip revenues. Such a situation occurred again in fiscal years 1976 and 1977 under Gov. Dan Walker and in fiscal 1978 under Gov. James R. Thompson. No tax increase resulted in any of these years. How did they prevent it? A. James Heins, an economics professor at the University of Illinois, says, "The term 'fiscal crisis' grossly misleads. It was not a crisis; and the problem was not fiscal. The problem was political and of less than crisis proportions." Precisely. All that had to be done was cut back spending. It was the only alternative to the unthinkable tax rise.

In this most recent "crisis" we saw former Gov. Walker faced early-on with the biggest, juiciest pie Illinois government had had in years. The 1969 income tax had not only financed state spending increases, but had allowed for the buildup of a cash reserve of $453 million by the end of 1974. Gov. Walker spent it. But, as Heins points out, "The problem with spending $400 million excess cash in three years lay in the resulting anticipation for more spending." So when Thompson took office in the middle of fiscal 1977 there was a momentum in spending and no reserve to speak of, and there was an employee pay raise due.

Thus Thompson's first budget, for fiscal 1978, had to be tight (or to use Thompson's word "austere"), otherwise a tax increase would be inevitable. Thompson, like most governors before him, blamed his predecessor for overspending, leaving a small cash reserve for him (although Ogilivie did leave a reserve for Walker, he undoubtedly

December 19771 Illinois Issues/9

hoped to spend it himself when reelected). Thompson held down spending. According to Heins "... he did what had to be done — it wouldn't have mattered who the governor was."

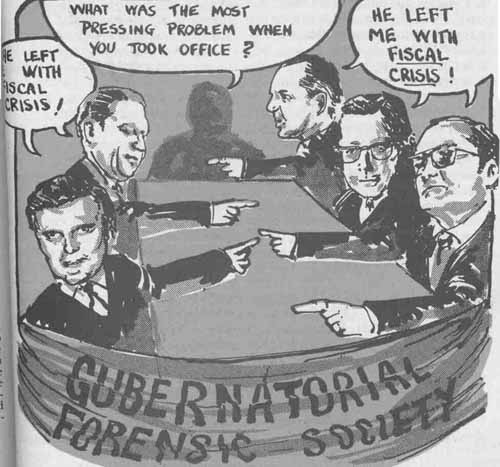

It is almost traditional for an Illinois governor to be challenged on budget matters by a constitutional officer of the opposition party. This most recent crisis saw Republican Gov. Thompson being challenged by Democrat Comptroller Michael J. Bakalis, not for spending too much but for being too tight. Under Democrat Gov. Walker it was Republican Comptroller George W. Lindberg who constantly warned about the dangers of overspending. Before that it was Republican Gov. Ogilvie being challenged on budget matters by Democrat State Treasurer Adlai E. Stevenson III.

In earlier, simpler times the conflicts between pie-slicing foes were not so publicly displayed. Under the auspices of the old Illinois Budgetary Commission, the budget was determined in a more personal way. In those days the legislative leaders and power brokers would sit down in an office together with the governor often for an all-night session. They would accomplish essentially the same things in the same spirit of mixed compromise and partisanship as today, only in a more direct way.

But in the latest case it was ironic that the battle line was drawn between the men who would soon win their respective parties' nominations and run against one another for the governorship. And, certainly, if elections were decided upon such contests of fiscal prescience, Gov. Thompson would win the upcoming election hands down. Bakalis continually predicted that state revenues by the end of fiscal 1977 would total about $50 million more than Gov. Thompson had predicted. While, in fact, the governor's predictions were within a few thousand dollars of the final fiscal 1977 balance.

Bakalis freely admits his mistake now, saying, "We really weren't prepared to make those kinds of judgments and we just missed the whole thing." Clearly this admission is not the kind that inspires confidence or prevents criticism, painfully honest as it is.

One of the first to criticize Bakalis on this point was Bureau of the Budget (BOB) director Robert Mandeville, who supplied the governor's accurate figures throughout the debate. "He was acting irresponsibly," Mandeville said. "We're not playing for tiddly winks here." Actually, Mandeville probably had the better position to determine the final outcome. He had just come from a long stint in the comptroller's office under Lindberg and eased superbly into his position of practical power, since the BOB (under the governor's office) can to some extent control the figures showing on state accounts at the fiscal year's end.

According to the report of a fiscal commission appointed by Gov. Thompson in January of 1977, "The State's accounting policies and procedures . . . present the opportunity to manage the checkbook balance by speeding up the recognition of receipts into the revenue accounts. This is possible because tax payments, for example, are not recognized as State revenue at the time they are physically received by the Dept. of Revenue. Tax collections and other similar collections of State revenue become recognized in the financial accounts maintained by the Treasurer and the Comptroller only after they have been deposited into the Treasurer's 'clearing accounts' and processed through the banking system."

The report also points out that accounting techniques in government are quite different from those of private corporations. For one thing state governments must always operate "in the black." They cannot borrow on the short term, thus cash position is all important. Corporations, however, are more concerned with the balance statement. In addition, the state treats property — such as auto and office equipment — as an ongoing expense item and does not allow it to build up depreciation as corporations do.

The report was critical of the state's accounting system, charging that the present legal mandate charging the comptroller to keep tabs on state spending is not being enforced. "In other words," the fiscal commission said, "the State does not have a centralized data base of bills to be paid. Information on unpaid bills at the end of the fiscal year becomes available only as requests for payment move through the bill-paying system from the agency incurring the obligation to the Comptroller's Office where the checks are finally written.

"This means that the Commission and interested citizens, investors and others are unable to determine the results of financial operations on a basis that is comparable to the financial reports of private enterprise," the report concluded. It then recommended "that the State provide its Comptroller with resources and legislation, if necessary, to bring the State's accounting system up to the standards of generally accepted accounting principles."

If all this sounds easy as taking candy — or a pie — from a baby, one should reconsider. Aside from the differences between corporate accounting and government bookkeeping mentioned above, Ray Coyne, executive director of the Illinois Economic and Fiscal Commission, says, "The accounting profession has developed in very sophisticated ways that aren't always transferable to government." Coyne also maintains that the state can and does keep close track of expenditures through a system known as "encumbrance accounting," whereby all prospective expenditures, such as contractual services, are required to be obligated with vouchers.

Yet most fiscal experts involved in Illinois government agree that some improvements could be made in accounting and controlling spending, Comptroller Bakalis, for instance, believes the state should "get a way from the misleading concept of the end of the month balance." He believes the state should direct its attention to the average daily balance "and then the balance over the course of the month."

The Illinois Task Force on Governmental Reorganization recommended that when revenues drop below levels allocated in the state budget, the governor should have the power to cut spending in executive departments. The absence of a direct mechanism for expenditure control, a relatively 'fine tuning' device, also forces the governor occasionally to use the amendatory or item veto which tends to cause confrontation and confusion in such areas as education finance," the reorganization report said.

It recommended "that statutory authority be given the governor to reduce executive branch expenditures to match anticipated revenues," not only in departments run by his own appointees, but in those headed by other elected officials. "Such reductions should be generally proportional, with equity being the primary concern," the task force said. It also recommended a 5 per cent limit on reductions on any one fund

10/ December 19771 Illinois Issues

to prevent abuse.

A different approach to prevention of "fiscal crises" is offered by U. of I. economist Heins, who says state income and sales tax rates need changing every year: "I suggest that Illinois move to a method of finance used by local levels of government. The legislature establishes the amount that the state must spend to meet its legitimate needs. After deducting other sources of money, federal grants and other state sources, the income (or sales) tax rate could be set so as to generate the required revenue."

Less controversial proposals were offered by the Illinois Economic and Fiscal Commission in a May 1977 report on "Legislative Control of State Finance." The legislative commission called for a return to a budget book "with integrated line item and program data." To control bond authorization, which is spending that borrows from future state resources to pay for present capital facility construction and renovation, the commission recommended that a fiscal note be attached to all bills authorizing bond sales. The notes would have to specify future year principal and interest payments on the bonds. (The state as of June 30, 1976 owed $1.369 billion in principal and $.765 billion in potential interest for general obligation bonds — a potential fiscal crisis quite a part from the more cyclical budgetary ones. The debt is nearly seven times the amount owed six years earlier.)

Another type of hidden future debt comes from spending for state pension programs. The commission recommended that the General Assembly require the governor to propose clearly in his budget book the level of funding he recommends for all current and future pension liabilities.

No matter how it's managed, it seems a sure bet that Illinois will avoid a tax hike in 1978. Former Comptroller Lindberg calls this "the essence of politics." Economist Heins says it springs from a decreasing demand for those state services where most of the money is spent — the big pieces of pie, namely education, health and welfare.

Gubernatorial candidate Bakalis agrees and says the last fiscal crisis was mainly the result of an opposite trend which must now be reversed and is being stemmed. But he gives the credit to the legislature: "The key turning point occurred under the last legislative session under Walker. That's when the legislature drastically reduced expenditures."

Incumbent Gov. Thompson and BOB director Mandeville take the credit themselves and point out that the state had been overspending prior to this administration. General fund yearly spending exceeded revenues by $138 million in fiscal 1975, by $189 million in fiscal 1976, and by $74 million in fiscal 1977 — the last budget under Walker (the balance was always in the black during those years, but it dwindled).

The BOB estimates that fiscal 1978 will see an end to deficit spending, with new revenues exceeding new spending by $37 million. It points to the state's monthly cash "checkbook balance" — money in the General Revenue Fund used to pay for basic government services. Year-end status of this balance has begun an upward swing for the first time since the fiscal 1974 high of $453 million. It is expected to reach $85 million by the end of this fiscal year, rising from the low $52 million balance at the end of fiscal 1977. That low was the result of heavy spending in the Walker administration. It was what was meant by "fiscal crisis" since such a low balance represents only about a day and a half of state spending — a very thin crust.

December 1977 / Illinois Issues/11