|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

Illinois Issues Humanities Essays (third series) Illinois' forgotten labor history By WILLIAM J. ADELMAN BARBARA NEWELL in her book, Chicago and the Labor Movement (University of Illinois Press, 1961), writes about the uniqueness of the Chicago and Illinois labor movement. Some of America's greatest labor leaders, like John L. Lewis, Sidney Hillman, John Mitchell, Mother Jones and Eugene V. Debs, got their starts in Illinois, and this state has always provided leadership to the national labor movement. Before 1900 one out of every four organized workers in the United States lived in Illinois, and few if any states have contributed more to the history of American labor than Illinois. For a variety of reasons, dozens of national unions — from clothing workers to meatcutters, from miners to bookbinders, from restaurant workers to teachers — were founded in Illinois. Perhaps it was because the Welsh miners, the Jewish clothing workers and the German carpenters brought with them from the Old Country a strong labor tradition. Perhaps it was because of the situation on the East Coast, where boat loads of new immigrants arriving daily were willing to work for the lowest wages. The older immigrants who migrated westward to Illinois, who had lost their jobs in the East, may simply have decided that it was time to take a stand, and unions were the only way they could fight for their collective rights. But given the curricula of most public schools in this state, most students leave school without a sense of this rich and important element in Illinois' history. Few could identify Lewis or Jones or Debs, and not many more could tell you the significance of events like Haymarket or Pullman. When William Bork, now director of the Labor Education Division at Roosevelt University attended Washington High School on Chicago's south side, he was never introduced to labor history. Only years later, while a student at the University of Illinois, did he learn that his American History classroom at Washington had overlooked the very field where the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937 had taken place. Bork eventually learned about this event and its significance, but most Illinois students are not so fortunate. 22/May 1984/Illinois Issues This lack of historical perspective borders on the disgraceful and dangerous. Local, state, national and international news stories on labor issues appear daily in newspapers, and on radio and television. Young people and adults read about the PATCO, Greyhound and Continental Airlines strikes. They read and hear of Lech Walesa and the Polish Solidarity movement. Yet without a background in labor history it is impossible for them to understand the true significance of any of these events. To rectify this situation, the Chicago and Illinois Federations of Labor have passed numerous resolutions over the years, calling for the schools to teach about the contributions of the labor movement to our state and national life. Yet despite these efforts most Illinois students still remain unenlightened about our rich labor heritage and its importance. There is a danger in this ignorance. As George Santayana put it: "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." Our state and nation can ill afford any repetitions of events like the Memorial Day Massacre, nor can we allow the distortions and inaccuracies that appear in the few textbooks that even mention this event. Will Scoggins, a California professor who conducted a study of textbooks (Labor in Learning: Public School Treatment of the World of Work, University of California, 1966), found, for example, the following statement about the Massacre in one U.S. history text: Swinging clubs, police advance upon nearly 2,000 steel strike demonstrators at the South Chicago plant of the Republic Steel Company in 1937. Ten people were killed during the demonstration. The violence and bloodshed caused the public to turn against the C.I.O. temporarily. Yet the facts of the matter were significantly different. Only about 300 pickets were in the area, for one thing. For another, the 10 people killed were all shot in the back or side by the police as they fled. Paramount newsreels of the event so shocked the public that the Senate conducted a special investigation

This pattern of action, reaction, distortion and correction mirrors the status of labor history in the schools over the years. In the Progressive Era (1898-1917), the works of historians like Mary and Charles Beard, which stressed the significance of labor history, were elements of many schools' curricula. By the 1920s, however, labor history had disappeared, and "The American System," a pamphlet published in Chicago by anti-labor business groups, was supplied to schools across the country. From this publication, young people learned that unions were un-American and that the "American Way" was for each worker to bargain individually with his employer, in keeping with the so-called '' Frontier Tradition." With the coming of the Great Depression and Roosevelt's New Deal, the story of the worker was again taught in the schools, and books like Louis Adamic's Dynamite (Harper, 1931) and Matthew Josephson's The Robber Barons (Harcourt, 1934) brought labor history home to the public. Josephson's book was dedicated to Charles and Mary Beard. At the same time, the Federal Theatre Project encouraged the writing of plays and radio dramas with labor themes, and WPA art celebrated the worker and the farmer on the job. The original Illinois Guide (1939), which was written as part of the WPA's Federal Writers' Project, was filled with this state's labor history. It is heartening that it has recently been reissued in paperback with the same pictures and text as the original. After World War II the pattern of the 1920s was repeated. The McCarthy "Red Scare" was also anti-union, and union members, teachers and researchers remained relatively silent on labor issues until the early 1960s. Historians like Jesse Lemisch, who worked in the early 1960s at the University of Chicago, and Staughton Lynd, who was at Roosevelt University for a short time, preached the gospel of history written from the bottom up, instead of from the top down. Instead of teaching only about politicians, big businessmen or even union leaders, these new historians believed the story of the average citizen and worker should be emphasized. This led to oral history projects and new research by people like David Brody, David Montgomery, Herb Gutman, Phil Foner and Alfred Young, the latter at Northern Illinois University. In 1967, a group of union members, labor attorneys, former Wobblies, early CIO members, history buffs, labor educators and academics formed a group devoted to correcting the inaccuracies in the public's perception of labor history. At first they were interested only in correcting misconceptions about the Haymarket Affair, and they called themselves the Haymarket Memorial Committee. By 1968 they had expanded their concerns, taking the name of the Illinois Labor History Society (ILHS), and assuming the following goals: It shall be the purpose of the Illinois Labor History Society to encourage the preservation and study of labor history materials of the Illinois Region, and to arouse public interest in the profound significance of the past to the present. By 1983, the ILHS had assisted in the founding of 21 other such organizations across the country. Now there is talk of founding an umbrella organization: a National Labor History Society. May 1984/Illinois Issues/23  The educational potential At a time when educators recognize the artificiality of the boundaries between traditional disciplines, the study of labor history offers unique and important possibilities as an interdisciplinary subject. Labor's story can be taught through music, poetry, film and photographs. Labor history can be examined from the perspectives of programs in black studies, ethnic and immigrant studies, urban studies and women's studies; and traditional programs in economics, history and government could readily use examples from labor studies to illustrate principles. Programs in industrial arts and vocational training could be enriched by some attention to labor issues. District 1199 of the National Unions of Hospital and Health Care Employees has pioneered in introducing "worker culture" into music, art and literature classes. Through its "Bread and Roses Project," this group has produced plays and musicals for hospital workers and developed books and posters which tell labor's story. Its collection of art, quotations and poetry, entitled Images of Labor, includes an introduction by Irving Howe and a preface by Joan Mondale and would make an attractive supplement to any English classroom. Other resources abound, ready for the alert and sensitive teacher to blend into study units in a variety of courses. Labor songs like those included on the classic record, Talking Union (Folkways, FH 5285), could enrich both music and history classes. The album contains a booklet with the words of the songs plus historical notes by Pete Seeger and Phil Foner. An article titled "Chicago's Singing Workers" by Josh Dunson appeared in the magazine Come For To Sing (Winter, 1980) on how to use labor songs in the classroom. Among the songs was a long lost one titled "The Sweat Shop" which had been written at Jane Addams' Hull House in the early 1900s: Toiling and toiling and toiling,

Endless toil, For whom? For what? Why should the work be done? I do not ask or know, I only toil, I work until the day and night are one. The poetry of Carl Sandburg is filled with labor history and labor themes — poems like "A Teamster's Farewell," "Blacklisted," "Working Girl" or "Chicago." "Memoir of a Proud Boy" is about Mother Jones and the Ludlow Massacre. Poems like "Joliet," "Clinton South of Polk," "Halsted Street Car" and "Blue Island Intersection" tell the stories of workingclass neighborhoods and cities. Hollywood has again discovered the worker in films as varied as Nine to Five, Norma Rae, Silkwood and Harlan County, U.S.A.; and a new series of educational films, produced by Elsa Rassbach and Public Forum Productions, will soon be appearing on PBS. The first of these docu-dramas, titled The Killing Floor, will be aired this spring. It is the story of the Chicago race riots of 1919 in the stockyards when employers played black and white workers against each other in order to break the union and pay the lowest possible wages. Teachers can prepare their students for this program by having them read Upton Sinclair's The Jungle and Carl Sandburg's The Chicago Race Riots with its introduction by Walter Lippmann. Both books are readily available in paperback. 24/May 1984/Illinois Issues Another film soon to be aired is The Gentle Crusader being produced by Film Boston Inc. It is the story of Jane Addams and Florence Kelley and their fight in the early 1890s for the health and safety of immigrant and native sweatshop workers. Old photographs can be useful tools in the classroom, especially historic photos by Louis Hine, Jacob Riis and Dorothea Lange. Two books filled with such pictures are America and Lewis Hine (Sperture, 1977) and The Eye of Conscience (Follett, 1974). In 1976 the ILHS took thousands of photos of workers across Illinois as a bicentennial project. These pictures were put together in an exhibit which toured the state as well as in book form (On the Job In Illinois: Then and Now). A mini-version of the photo exhibit is still available for rental by school or union groups. In women's studies the teacher can recount the story of Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr and their pioneer work with trade unions. Mary McDowell, "The Angel of the Yards," organized a settlement house through the University of Chicago and helped Czechs, Poles, Lithuanians and other ethnic groups find a better life in the stockyards. A film, Packingtown U.S.A. (University of Illinois Film Library, 1969), tells the story of her work with the Amalgamated Meatcutters Union. Agnes Nestor, who organized the Glove Workers Union, went on to become president of the Women's Trade Union League which fought against child labor and for the right of women to vote. The list of women who worked directly or indirectly with unions in the fight for social change is endless. Two excellent books give a more complete list: We Were There: The Story of Working Women in America (Pantheon, 1977) by Barbara Wertheimer, and The Roads They Made: Women in Illinois History (Kerr, 1977) by Adade Wheeler. For those who wish to take a field trip dealing with women's history, Babette Inglehart of Chicago State University has put together an indispensable booklet: Walking With Women Through Chicago History (Chicago, Salsedo Press, 1981). Since the Illinois School Code requires the teaching of the contributions of ethnic groups, the teacher has the opportunity to point out the role that immigrants have played in the development of the American labor movement. The way in which some employers played ethnic groups against each other

Blacks have also played an important part in the history of the American labor movement. A. Phillip Randolph organized the Pullman Sleeping Car Porters and helped organize the great Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated while trying to organize the municipal garbage collectors in Memphis, Tenn. A small booklet, Labor and the Government (Cornell University, Bulletin 56, ILR, April 1964) by Sayre and Rowland, can be used to introduce labor issues into a civics or government class. This gives the instructor the opportunity to point out the democratic structure of labor unions and how they parallel the structure of local, state and federal government. The Illinois School Code also calls for school districts to work with employers and unions as a part of vocational education and pre-apprenticeship programs. A government pamphlet, Apprenticeship: Past and Present (U.S. Department of Labor, 1977), gives an excellent history of indenture and the struggle of the apprentice to win justice and rights on the job. Industrial arts programs give the teacher an opportunity to teach the student what life is really like on the job. A number of years ago a teacher in Bensenville organized his industrial arts class into a union and had the students elect a shop steward to handle their grievances. This introduction of the union into a practical course enriched the classroom experience of these students in a way they would never forget. The Illinois School Code recognizes the value of educational tours. Why not a trip to a union hall or an historic union site? Illinois is filled with such sites. A few years ago I wrote an article on this topic, "Labor History Through Field Trips," for the book Labor Education for Women Workers (Temple University Press, 1981), edited by Barbara Wertheimer. To explore more fully the available resources and potential benefits of labor studies in the curriculum, it might be best to focus on three specific events from Illinois' rich labor history: the Haymarket Affair of 1886, the Pullman Strike of 1894 and the work of Mother Jones who spent 59 years of her life fighting for labor's cause. The Haymarket Affair Probably no single event has influenced the history of labor in Illinois, the United States, and even the world, more than the Chicago Haymarket Affair. It all began with a simple rally on May 4, 1886, but the consequences are still being felt today. Although this story is included in almost all American history textbooks, very few present the event accurately or point out its significance. To understand what happened at Haymarket, it is necessary to go back to the summer of 1884 when the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, the predecessor of the American Federation of Labor, called for May 1, 1886, to be the beginning of a nationwide movement for the eight-hour day. This wasn't a particularly radical idea since both Illinois workers and federal employees were supposed to have been covered by an eight-hour day law since 1867. The problem was May 1984/Illinois Issues/25  that the federal government failed to enforce its own law, and in Illinois, employers forced workers to sign waivers of the law as conditions of employment. that the federal government failed to enforce its own law, and in Illinois, employers forced workers to sign waivers of the law as conditions of employment.

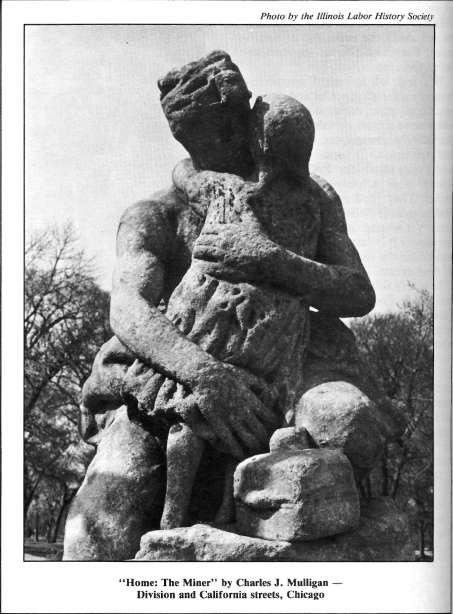

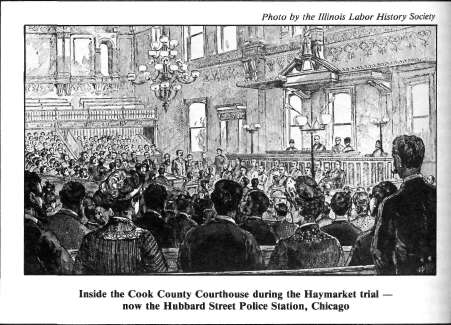

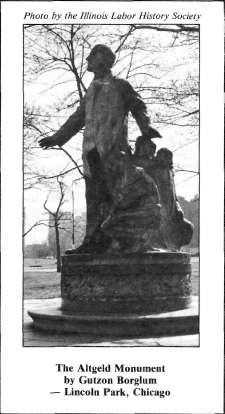

With two years to plan, organized labor in Chicago and other parts of Illinois sent out questionnaires to employers to see how they felt about shorter hours and other issues, including child labor. Songs were written like "The Eight Hour Day" (available on American Industrial Ballads, Folkways, FH 5251); everywhere slogans were heard like "Eight Hours for Work, Eight Hours for Sleep, and Eight Hours For What We Will!" or "Shortening the Hours Increases the Pay." Although perhaps a simplistic solution to unemployment and low wages, the "Eight-Hour Day Movement" caught the imagination of workers across the country. Chicago with its strong labor movement had the nation's largest demonstration on Saturday, May 1, 1886, when reportedly 80,000 workers marched up Michigan Avenue arm-in-arm singing and carrying the banners of their unions. The unions most strongly represented were the building trades. This solidarity shocked some employers, who feared a workers' revolution, while others quickly signed agreements for shorter hours at the same pay. Two of the organizers of these demonstrations were Lucy and Albert Parsons. The beautiful and talented Lucy had been born a slave in Texas about 1853. She had some Indian blood and spoke Spanish, and she worked for the Freedmen's Bureau after the Civil War. After her marriage to Albert, they moved to Chicago where she turned her attention to writing and organizing women sewing workers. Her husband Albert was a printer, a member of the Knights of Labor, editor of the labor paper, The Alarm, and one of the founders of the Chicago Trades and Labor Assembly. On Sunday, May 2, Albert went to Ohio to organize rallies there, while Lucy and others staged another peaceful march of 35,000 workers. But on Monday, May 3, the peaceful scene turned violent when the Chicago Police Department attacked and killed picketing workers at the McCormick Reaper Plant at Western and Blue Island avenues. This attack by the police provoked a protest meeting which was planned for Haymarket Square on the evening of Tuesday, May 4. Very few textbooks provide a thorough explanation of the events that led to Haymarket, nor do they mention that the pro-labor mayor of Chicago, Carter Harrison, gave permission for the meeting. While the events of May 1 had been well-planned, the events of the evening of May 4 were not. Most of the speakers failed to appear. Instead of starting at 7:30, the meeting was delayed for about an hour. Instead of the expected 20,000 people, fewer than 2,500 attended. Two substitute speakers ran over to Haymarket Square at the last minute. They had been attending a meeting of sewing workers organized by Lucy Parsons and her fellow labor organizer, Lizzie Holmes of Geneva, Ill. These last-minute speakers were Albert Parsons, just returned from Ohio, and an English-born Methodist lay preacher who worked with the labor movement, Samuel Fielden. The Haymarket meeting was almost over, and only about 200 people remained when they were attacked by 176 policemen carrying Winchester repeater rifles. Fielden was speaking; even Lucy and Albert Parsons had left because it was beginning to rain. Then someone, unknown to this day, threw the first dynamite bomb ever used in peacetime in the history of the United States. The police panicked, and in the darkness many shot at their own men. Eventually seven policemen died, only one directly accountable to the bomb. Four workers were also killed, but few textbooks bother to mention this fact. The next day martial law was declared, not just in Chicago but throughout the nation. Anti-labor governments around the world used the Chicago incident to crush local union movements. In Chicago labor leaders were rounded up, houses were entered without search warrants, and union newspapers were closed down. Eventually eight men, representing a cross section of the labor movement, were selected to be tried. Among them were Fielden, Parsons and an ordinary young carpenter named Louis Lingg, who was accused of throwing the bomb. Lingg had witnesses to prove that he was over a mile away at the time. The two-month-long trial that followed ranks as one of the most notorious in American history. The Chicago Tribune even offered to pay money to the jury if it found the eight men guilty. Eventually, three of the men were sent to Joliet Penitentiary and five, including Parsons, were condemned to death by hanging. Louis Lingg mysteriously died when his face was blown away by a dynamite cap while he was in a well-guarded cell and in solitary confinement. In June of 1893, Gov. John P. Altgeld pardoned the three men still alive and condemned the entire judicial 26/May 1984/Illinois Issues system that had allowed this injustice. While textbooks tell about the bomb, they fail to mention the reason for the meeting or what happened afterwards. Some books even fail to mention the fact that many of those tried were not even at the Haymarket meeting, but were arrested simply because they were union organizers. The real issues of the Haymarket Affair were freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to free assembly, the right to a fair trial by a jury of peers and the right of workers to organize and to fight for things like the eight-hour day. Sadly, these rights have been abridged many times in American history. During the civil rights marches of the 1960s, the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and the 1968 Democratic National Convention, we saw the most recent examples of similar violations of our constitutional rights. To date there is no educational film dealing with the Haymarket Affair, although this incident and its tragic aftermath could make a moving story. There is no play yet to dramatize one of the most unjust trials in American jurisprudence. But there are a number of excellent books and poems as well as monuments and historic sites that can be visited as part of a field trip. The definitive book was written by Henry David, The History of the Haymarket Affair (Farrar & Rinehart, 1936). In 1976 the ILHS published Haymarket Revisited, a walking-driving tour book of sites connected with the Haymarket Affair. That same year the ILHS also published a marvelous book about Lucy Parsons. This book by Carolyn Ashbough, Lucy Parsons: American Revolutionary (Kerr, 1976), traces Lucy's life from her childhood as a slave in Texas to her tragic death in a fire in Chicago in 1942. A novel that can be used in English classes is The Bomb by the colorful Frank Harris (University of Chicago Press, reissued in 1962). Although published as fiction, most of this story is historically accurate, and students in English as well as history classes could benefit from it. Harris has the bomb thrower recounting the story on his deathbed as he admits being hired by management to throw the dynamite bomb in order to discredit the labor movement. There are two excellent books dealing with the infamous trial. The first is Dyer Lum's reissued book, Trial of the Chicago Anarchists (Arno Press, 1969), which is a collection of transcripts from the trial. The second, by Bernard Kogan, The Chicago Haymarket Riot: Anarchy on Trial (Heath, 1959), was written for use by English classes as a model for doing a research paper. This book is filled with newspaper accounts of the trial, appeals to higher courts and statements by the presiding judge Joseph E. Gary, the attorneys and Gov. Altgeld. Classes at Fenton High School in Bensenville have used for many years a pamplet titled Political Justice: The Haymarket Three (American Education Publications, 1972) by Vincent Rogers, in which the Haymarket trial is compared to the Chicago Eight trial.

The poetry of Carl Sandburg includes a poem, "Dynamiter," which depicts a fictional German worker as a warm and caring person despite "his deep days and nights as a dynamiter." Sandburg had to beg his publisher, Alfred Harcourt, to include this in his Chicago Poems of 1916 because of the Haymarket controversy. And the play Front Page by Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, although not about Haymarket, is set in the same courthouse and jail that housed the Haymarket martyrs. This story is about another supposed "anarchist" who is about to be hanged on the same gallows used during the Haymarket hangings. This play makes a comedy out of the reaction of the newspapers, government and the public. The Haymarket Affair took on worldwide dimensions in July of 1889, when a delegate from the American Federation of Labor recommended at a labor conference in Paris that May 1 be set aside as International Labor Day in memory of the Haymarket martyrs and the injustice of the Haymarket Affair. Today in almost every major industrial nation, May Day is Labor Day. Even Great Britain and Israel have passed legislation in recent years declaring this date a national holiday. For years, half of the American labor movement observed May 1 as Labor Day, while the other half observed the first Monday in September. After the Russian Revolution the May 1 date was mistakenly associated with communism, and as a protest against Soviet policy the May 1 date was first proclaimed Law Day in the 1960s. Today, the Illinois School Code calls for Illinois Law Week to be observed in the schools during the first week in May. For a number of years New Trier High School in Wilmette has included the story of Haymarket as a part of their Law Day observances, capitalizing on a perfect opportunity to teach about this event and the effect it has had on world history. The year 1986 will mark the centennial of the Eight-Hour-Day Movement and the Haymarket Affair. Folk singer Pete Seeger and a group called "The People Yes," named after Sandburg's volume of poems by that name, are planning a nationwide celebration, an event which offers teachers a unique opportunity to teach the facts about Haymarket and to correct the distortions and inaccuracies in our textbooks. May 1984/Illinois Issues/27 Pullman: the company town The story of Pullman before, during and after the strike of 1894 offers the teacher, student, citizen or union member a unique opportunity to study the operation of an early multinational corporation and the terrible mistakes it made. Some of these same mistakes are being made by corporations today. In 1880, George Pullman commissioned architect Solon Beman to begin construction of a so-called "model" town for the production of his sleeping cars and for the housing of his workers. A buffer zone was provided between the town and Chicago so that the workers would be separated from the evil influence of the city. Workers hired were carefully screened to assure industrious, nondrinking, American-born workers, who were not union members. But even though the town was beautiful, there was nothing American about it; it was more like a feudal state. Pullman always called his workers "my children." They had no democracy in their community or on the job. Although there were walkouts and a constantly changing work force from the beginning, serious problems developed in 1883 when Pullman reduced wages from 25-54 percent without any reductions in the rents workers paid or in what they were charged for water and gas by the company. When a committee of workers asked to talk over their grievances with management, the members were fired. Eventually the entire town went on strike. A young Methodist minister, the Rev. William Carwardine, could no longer stand to see members of his Pullman congregation starving. He and Jennie Curtis, a teenage Pullman laundry worker, went to the convention of the American Railway Union (ARU) in June of 1894 to ask for help. Against even the wishes of ARU President Eugene V. Debs, they convinced the delegates to back the Pullman workers against the powerful Pullman Palace Car Company. The ARU agreed to refuse to move any train carrying a Pullman car. The General Managers' Association (GMA), made up of 24 railroads centering or terminating in Chicago, saw this as a battle to the death between labor and management. They came to Pullman's aid by placing Pullman cars on freight and mail trains, thereby creating a national emergency in order to force federal intervention. The Sherman Anti-Trust Law, passed to control monopolies like Standard Oil, was used instead against Debs and the ARU. An injunction was issued, and 14,000 federal troops and special deputies were sent to Chicago on July 2. Debs was arrested and thrown into the same cell at the Cook County Jail that had once held one of the Haymarket martyrs. Another unjust trial followed, and he was given a six-month sentence — but not in Cook County. Chicago workers had threatened to tear down the jail and free Debs if he were incarcerated there. Instead he was sent to McHenry County Jail in Woodstock. When he was released after serving his time, a special train brought him to Chicago and over half a million people greeted him, wrapped him in an American flag and carried him on their shoulders through the streets. The entire nation took sides in this dispute: Those supporting the Pullman workers and the ARU wore white ribbons on their lapels; those supporting Pullman and the GMA wore small American flags. Jane Addams came out in support of Jennie Curtis and the other women workers of Pullman. Clarence Darrow quit his lucrative job as an attorney for the Northwestern Railroad in order to defend Debs. Chicago Mayor John P. Hopkins, who had once been a Pullman employee, and Gov. Altgeld sided with the union. George Pullman was forced to turn to his powerful friends in Washington, including President Grover Cleveland and U.S. Atty. Gen. Richard Olney. Even a conservative businessman like the powerful Marcus Hanna was against Pullman because of the anti-business attitude his actions had caused. Pullman died in 1897, still unaware that he had done anything wrong. By 1907, the Illinois Supreme Court had ordered the Pullman Company to sell the homes, stores, churches and everything it owned that was not needed for the construction of sleeping cars. Eventually annexed to Chicago, the community was threatened with destruction after World War II when the area was proposed for a new industrial site. The people fought to save their homes, and in 1973 the Pullman Community was declared a National Historic District. Today it is a "Midwestern Williamsburg" containing over 750 pieces of property, and a number of the major buildings and many of the homes have been restored. Unlike Williamsburg, however, Pullman is still a working community of small homeowners. This is the perfect place for a field trip; yet if you take a tour conducted by the Historic Pullman Foundation, you will hear little about the Pullman Strike, Eugene V. Debs, Rev. Carwardine, Jennie Curtis, Clarence Darrow, Jane Addams and others connected with the labor side of the story. You will hear a great deal about George Pullman and the architect Solon Beman and their so-called "perfect" community. In order to tell the labor side of the story the ILHS reissued in 1971 The Pullman Strike (Kerr, 1894) by Rev. Carwardine. In 1972, the ILHS published Touring Pullman: A Study in Company Paternalism, a walking-driving tour guide of the community. Although this book is not sold by the Historic Pullman Foundation because of its labor viewpoint, it is available from the ILHS and the Chicago Historical Society. By reading this book and then taking an Historic Pullman Foundation tour, one can get both sides of the story. A number of other books are available to those interested in the full story of Pullman. The classic by Almont Lindsey, The Pullman Strike (University of Chicago, 1942), is still available in paperback as is a newer book by Stanley Buder, Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning (Oxford, 1967). Recently, two new educational films on Pullman were released. When Martin Buechley, a young filmmaker, tried to get funding for an historic film on Pullman, many groups turned him down on the assumption that there were dozens of films on this subject. He had to prove to the funding agencies that except for a brief mention of the event in the Britannica film, Rise of Labor, absolutely no film on Pullman existed. On May 20, 1983, Buechley's Palace Cars and Paradise was premiered. This beautiful color film, funded by the Illinois Arts and Humanities councils, went on to win an award from the Illinois State Historical Society in October 1983, and will soon appear on PBS. It is available for rental from the ILHS. Another film on the Pullman Company is the recently completed Kartemquin Film, The Last Pullman Car (1984). This film covers the history of the company, including its final purchase by another multinational, the closing of the plant in 1982 and how it has affected the workers and their families today. 28/May 1984/Illinois Issues  Mother Jones In Mary Harris Jones, known as "Mother Jones," Illinois has an authentic folk heroine. Although born in Cork, Ireland, on May 1, 1830 (some think she took this day for her birthday because of Haymarket), and educated as a teacher in Canada and Michigan, it was in Illinois that she began her work with unions and it was in Illinois that she chose to be buried. In the early years of her marriage, her husband had been active with the Molders Union in Memphis, Tenn. But Mary Jones had four children to take care of and little time for union activities. In 1867, however, an epidemic hit Memphis; within a few days she had lost her husband and all her children. Trying to put the pieces of her life together again, she came to Chicago and opened a dress shop on Washington near Michigan Avenue, but that was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871. While camping in the ruins of St. Mary's Church near State and Madison, she heard singing from an adjoining ruin, and went to see what was happening. It was a rally of members of the Knights of Labor. From then on, she adopted the labor movement as her family — especially the children who were forced to work in the mills and mines. For the next 59 years Mother Jones went wherever union leaders asked her to go. Leaders like Terence Powderly of the Knights of Labor and later John Fitzpatrick of the Chicago Federation of Labor could count on Mother Jones' help whenever there was a strike and workers needed inspiration. When she was angry, they say "her language was so colorful she could make a mule skinner hang his head in shame." She once told a group of striking miners to stay home and mind the kids while she led their mop-carrying wives to chase the scabs out of the mines. For a few years Mother Jones worked in Chicago with the Molders Union organizing workers at the McCormick Reaper Plant and Crown Stove, but by 1877 she was in Pittsburgh for the Great Railroad Strike. Shocked by the Virden Riots of 1898, she stated then and there that when she died, she wanted to be buried next to those brave boys in the cemetary at Mt. Olive, Ill. Among her protege's were John Mitchell of Braidwood, one of the founders of the United Mine Workers (UMW) and its president from 1899 to 1908. When she became disappointed with Mitchell, she helped a young fellow from Panama, Ill., by the name of John L. Lewis, become president of the UMW — a post he would hold from 1920 until 1960. In 1903 Mother Jones led a "Children's March" across Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York in order to force President Roosevelt to take a stronger stand against child labor. In 1905 she sat on the platform in Brand's Hall at Erie and Clark streets in Chicago next to Eugene V. Debs and Lucy Parsons at the founding convention of the Industrial Workers of the World. In 1913 she was marching through the streets of Calumet, Mich., during the Great Copper Strike to protest the killing of two workers and the injuring of dozens by armed company guards. The next year she was in Ludlow, Colo., to protest the deaths of 11 children and two women who were burned when the tent city of the miners was set on fire on orders from John D. Rockefeller Jr. By July 5, 1917, she was back in Illinois again, this time to aid the transit May 1984/Illinois Issues/29 workers of Bloomington in their fight against the owner of the city transit system, who also happened to be a U. S. senator. Through the help of Mother Jones, they won their fight. In 1919 she assisted a young Phillip Murray, future head of the CIO, during the Great Steel Strike in South Chicago. In 1922, Nation magazine voted her one of the greatest women in America. In both 1920 and 1924, she was a major speaker at the Ashland Auditorium in Chicago at the conventions of the Farm-Labor Party, which supported Robert LaFollette for president in 1924 and polled nearly five million votes nationally. In 1925 at the age of 95 she was busy writing her autobiography. Mother Jones' impact on the labor movement can be measured by the national mourning at her death, at age 100, in Silver Springs, Md., on November 30, 1930. A funeral train bearing her body retraced the route of Lincoln's funeral train, traveling from Washington, D.C., to Chicago, Springfield and then on to the little mining town of Mt. Olive where, according to her wishes, she was buried. The entire nation listened to the radio as WCFL broadcast the funeral, and a Gene Autry recording, "Death of Mother Jones," sold thousands of records and helped establish Autry as a star. Six years later, with 50,000 people present, a monument was dedicated at her gravesite, and in Washington, D.C., a bust of Mother Jones by the sculptor Jo Davidson was placed in the foyer of the newly completed Department of Labor Building. By the early 1970s, Mother Jones had almost been forgotten. Even the Jo Davidson bust had been removed — it was finally found again in the mid '70s, broken and discarded in the corner of a subbasement closet. In 1972, the ILHS reissued The Autobiography of Mother Jones (Kerr, 1925), and a letter was written to the U.S. secretary of the interior requesting that the Union Miners' Cemetery and the Mother Jones monument at Mt. Olive be given landmark status. The reply from the secretary was: "Who is Mother Jones?" The ILHS then launched a campaign to restore her name to its rightful place in Illinois and American labor history. The ILHS twice held its annual meetings in Springfield and Mt. Olive. Folklorist Archie Green, author of Only a Miner: Studies in Recorded Coal-Mining Song (University of Illinois Press, 1972), played songs connected with Mother Jones and a wreath was laid on her grave. Today, Mother Jones has been rediscovered. Her grave is listed in the Register of Historic Sites, and the Jo Davidson bust is now in the National Gallery of Art. In 1974, Dale Fethering published a new biography, Mother Jones: The Miner's Angel (Southern Illinois University Press, 1974). A magazine now bears her name, and in 1978 a play about her toured the country. Books and pamplets about Mother Jones are available at every grade level. A beautifully illustrated book, Three Cheers for Mother Jones (Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1980), by Jean Bethell is available for students at the second grade level. Another book by Rhoda and William Cahn, No Time for School, No Time for Play (Jullian Messner, 1972), is available for students in the fourth and fifth grades. This book is not only the story of Mother Jones but deals with the entire question of child labor in America. It is filled with fascinating old photos, including one of a group of children carrying picket signs and demanding the right to go to school.

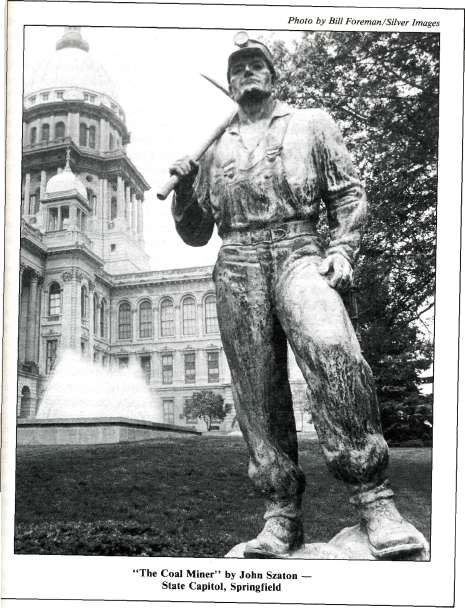

A book for junior high school students is Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America (Crown, 1978) by Linda Atkinson. A pamphlet for adults by Priscilla Long, Mother Jones: Woman Organizer (Red Sun Press, 33 Richdale Ave., Cambridge, Mass.), is also available. Several groups honored Mother Jones in 1980, the 50th anniversary of her death, but one of the most exciting programs was "The Mother Jones and the Miners Festival" organized in Charleston, W. Va., by Lois McLean, president of the West Virginia Labor History Association. McLean is also an active member of the Coal Miners Research Association and has worked with the students of North Cambria High School in preparing a book called Out of the Dark: Mining Folk, which has given the students a pride in their mining heritage. In Charleston last year she worked with the West Virginia Children's Theatre to produce a play about Mother Jones called There is an Old Woman. In 1980, the ILHS issued in booklet form The Union Miners' Cemetery (Kerr) by John Keiser, formerly of Sangamon State University. This booklet tells the story of Mother Jones and all the other union men and women buried in this, the only union-owned cemetery in the nation. It is located just off Interstate 55 at Mt. Olive. Also buried there are the victims of the Virden Riots of October 12, 1898. When the Chicago-Virden Coal Company refused to abide by a decision of the Illinois State Board of Arbitration regarding pay rates, the company decided to break the union, composed mostly of English, Welsh, German and Slavic miners, by bringing in nonunion black workers from Alabama. As might be expected, terrible rioting and bloodshed resulted. A local minister, sympathetic to the company, even refused burial in the church cemetery to the union men. The miners then bought their own land for a cemetery to bury their dead union brothers. But if the memory of Mary Harris Jones is honored in Mt. Olive as the mother of the American labor movement, it can also be said that the founding fathers of organized labor came out of the Illinois coal fields. The nation's first miners union, the American Miners' Association, was organized at a meeting in Belleville in 1861. Soon the "Miners' Hall" became, next to the church, the most important building in small mining towns throughout the state. Here miners met to lobby for laws to protect their lives. Coal was basic to the industrial development of Illinois, and from the very beginning the miners and their unions helped shape labor relations in the state as well as legislation dealing with hours, wages and workmen's compensation. 30/May 1984/Illinois Issues Employers tried to break the laws and the power of the unions by pitting one ethnic group against another. Miners from Italy were brought into the mines around Benld in Macoupin County. Attempts were made to break the militancy of the Braidwood miners, who were all originally Welsh and Scotch, by bringing in Czech, German, French and Irish miners. But employers were surprised when the miners of Braidwood regardless of ethnic background began to work together. John Mitchell of Braidwood would bring miners together in the UMW, and later it would be John L. Lewis who would organize the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) which organized unskilled workers of every racial and ethnic background during the late 1930s. Celebrating the heritage The materials and resources available on labor issues suggest the vast educational potential of this proud chapter in Illinois history. And across the state, various groups and individuals have begun to retrieve and celebrate labor's contributions to our economy and culture. Since 1978, for example, the Chicago Metro History Fair (60 W. Walton) has encouraged high school students in the metropolitan area to research their family and community histories. For the last two years, the winners of the $1,000 grand prize have been students who have written on labor themes. The first Danville History Fair was scheduled for April, and Danville's labor history was an important part of that celebration. The Will-Grundy Counties Trades and Labor Council has sponsored an art and labor show with paintings by Kathleen Farrell, an art teacher at Joliet Junior College. Part of the program was a slide show titled "Roll the Union On: Will County Labor History." The Bloomington-Normal Trades and Labor Assembly, in cooperation with Illinois Wesleyan University, has begun an oral history project that will include interviews with retired workers from the Chicago-Alton Railroad shops which played such an important role in the early history of this area. Efforts like these can serve as models for other labor groups in the state who wish to retrieve and preserve their history. And there is more help available. Alice Hoffman at Penn State, who has pioneered in oral history interviewing of union members, has written a booklet entitled Preserving the History of Local Unions. In Michigan, the Walter Reuther Library of Labor Affairs, in cooperation with the UAW has published Writing Your Local Union History. But if our labor heritage is to take its rightful place in the hearts and minds of Illinois citizens, then teachers, union members and other concerned citizens must work together to bring about the needed recognition. The most important thing that must be done is to get a strong amendment to the Illinois School Code providing for the teaching of labor history. At present, section 27-21 of the code, which provides for the teaching of United States history, lists among its goals a knowledge of the contributions blacks and other ethnic groups have made in the history of this country. To these goals should be added a knowledge of labor history. Such an amendment would not force schools into unwanted or expensive changes in the curriculum; rather — as has already been done in the fields of black history and ethnic history — it would give encouragement and impetus to interested teachers and communities. We have amendments providing for Arbor and Bird Day, Leif Ericson Day and American Indian Day. Each year the governor declares Black History Month and Women's History Week. An Illinois Labor History Week could focus attention on the struggles of Illinois workers for everything from the eight-hour day to the founding of the UMW — and from John L. Lewis and the CIO to the grass-roots fights of individual workers for democracy in their workplaces and their communities. Haymarket, Pullman and Mother Jones should become part of what students know about the complex and important past of the state in which they live.  We should take seriously the words of Hubert Humphrey, a member of a teachers' union and a friend of labor, who spoke these words in his last public address shortly before his death: The history of the labor movement

needs to be taught in every school in the land. . . . America is a living testimonial to what free men and women, organized in free democratic trade unions can do to make a better life. . . . We ought to be proud of it! About the author: William J. Adelman is a professor of labor and industrial relations at the University of Illinois and coordinator of the Chicago Labor Education Program. He is vice president of the Illinois Labor History Society and one of its founding members. He is the author of a number of books on Illinois labor history, including Touring Pullman (1972), Haymarket Revisited (1976) and Pilsen and the West Side (1983). May 1984/Illinois Issues/31

|