The state of state services to children is

awful, but can it get worse? Abuse and neglect of children

are rooted to causes no one agency can control

For the past few years, Rep. David D. Phelps (D-118, Eldorado) has received some troubling phone calls from caseworkers at Illinois' child welfare agency. Afraid to voice complaints to supervisors, the workers have vented their frustrations to the downstate Democrat because "they knew I couldn't fire them," said Phelps, who chairs the House Committee on Health and Human Services. "There's a fear of reprisal, of being misunderstood. There are no open lines of communication, and that's no way to run an agency like that. How can a system run properly like that?"

Mac Ryder

|

By now, anyone who has been paying even the slightest bit of attention knows that the system to which Phelps refers — the Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) — is, in fact, not running properly at all. As Gov. Jim Edgar said in his State of the State address:

"Our child welfare system is not broke;

it is broken." Problems range from charges that DCFS fails to adequately care for wards of the state to reports on its improper use of public funds — and these are just the ones that have been publicized by the media.

Also indicative of the child welfare agency's sad state of affairs is the fact that the governor had to search for months during a time of crisis in the agency to find someone willing and at least passably qualified to head it. Former director Sue Suter resigned from her post at the beginning of last September; not until February 5 did Gov. Edgar name the new director — Sterling "Mac" Ryder, DCFS general counsel who had been serving as acting director since Suter's departure.

The arduous search for and hiring of a director just marks the beginning of the agency's struggle to pull itself out from under a heap of lawsuits, consent decrees, scathing headlines, critics and general head-shaking and eye-rolling that often accompanies mere mention of its acronym. Sen. Donne E. Trotter (D-16, Chicago) summed the situation up like this: "We have let this department wallow in its own filth. You know the old saying, 'Things just can't get any worse?' That's the case here." But just about everyone who has knowledge of and interest in Illinois child welfare has a

different idea of what is needed to reform DCFS. And therein lies a disturbing question: Given the huge scope and problems of this agency, can things get any better?

"It's true that in bigger states, like Illinois, it's very, very hard to change the system," said Shelley Smith, who manages child and family welfare programs for the Denver-based National Conference of State Legislatures. "There are more reports of abuse, more cases to investigate . . . not only that but there can be more political turf battles as well," which may lure welfare officials' attention away from dealing with the serious, sometimes life-threatening problems plaguing their clients.

The appointment of Ryder to the agency's helm marks one area of disagreement. When describing him, both supporters and doubters preface their remarks by saying, "He's a nice guy." From there, they go in different directions, calling him a capable leader who can oversee needed reforms in the agency or branding him a lifelong bureaucrat who will be nothing more than a 'yes man' for the Edgar administration.

All in all, though, there is a common theme of empathy for his role. As Phelps put it, "We understand he's not inheriting a good situation." Sen. Judy Baar Topinka (R-22, North Riverside), who chairs her chamber's Committee on Health and Human Services, agreed. "He has to come from behind, unfortunately. It doesn't matter if it's Mac Ryder or anybody else — he deserves a badge of courage for jumping into that agency." Betty L. Williams, who chairs the Illinois Family Policy Council, a citizens panel that advises DCFS, is optimistic about the new director. "Whether he's going to solve our problems and be the greatest thing we've ever had I don't know," said Williams, who also is vice president for government affairs at the nonprofit United Charities in Chicago. "But he at least seems to be asking for discussion of innovative ideas, like working with the private sector to solve some of our problems."

Ryder, 53, is the first to acknowledge he's in a challenging position — not just because of the mangled systems within DCFS but because of the nature of its work. "Child welfare agencies across the country are by and large governments' point organizations for addressing some of society's most serious problems," he said. "Those problems

May 1993/Illinois Issues/15

manifest themselves in child abuse and neglect, and the child welfare agencies are called upon to make decisions about these crises. I think we have a lot of improving to do in Illinois."

A onetime grade school teacher who coached basketball

and baseball in Ludlow, Ryder began his state government career during his final year of law school, when he assisted the legislature in implementing the then brand-new 1970 state Constitution. He worked for years in the Legislative Reference Bureau, serving as its deputy director, and also

|

Family First aims

at family

preservation,

but does it work?

|

The anger and disagreement that color so many decisions and policies at the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) are perhaps most clearly visible in the controversial four-year-old Family First program.

Family First is aimed at helping troubled families through early intervention. Caseworkers are sent into homes to provide counseling and teach parenting and housekeeping skills so that parents can learn how to better care for their children. On paper, Family First targets parents with relatively minor problems;

those, for example, who are not substance abusers and who never have had a child removed from their home because of abuse or neglect. But it hasn't quite worked that way.

"The truth is every family we've served has had a substance abuse problem," said Sandy Roberts, who supervises a team of Family First caseworkers through United Charities on the south side of Chicago. DCFS contracts out Family First cases to private agencies like United Charities. "We've also had families who have had their kids taken by DCFS in the past. This isn't the population we were set up to serve."

And those aren't the only problems.

According to an evaluation of Family First by the University of Chicago's Chapin Hall Center for Children, the program has failed to keep significant numbers of children from being placed in foster care. In fact, while Family First caseloads were generally quite low — fewer than 10 per caseworker team — the children involved were just as likely to wind up being placed in foster care as were children receiving traditional services from DCFS.

These numbers frustrate Patrick T. Murphy, public guardian for Cook County juveniles. "I don't understand how they justify chauffeuring these families around, sending maids into those apartments. They're rewarding people for abusing their kids," he said incredulously.

But caseworkers and DCFS officials alike say Murphy's claims of luxury treatment for Family First clients are greatly exaggerated. "I don't know of one family in Family First who is happy to be there," said Roberts. She said Family First provides some transportation by van to clients — but generally only to places the clients don't particularly want to go, such as doctor's appointments or for drug tests.

DCFS Director Sterling "Mac" Ryder said he is afraid criticism like Murphy's will turn public opinion against efforts to keep families intact. Murphy is pushing an initiative in the legislature this session to keep parents convicted of physical or sexual abuse from receiving Family First services unless they are ordered by a juvenile court judge.

Several child advocates agree that while the program is far from perfect. Murphy's proposal would make family preservation efforts too difficult. Jerry Stermer, president of Voices for Illinois Children, said he thinks Family First is a vital part of child welfare in Illinois. "This works toward something Illinois public policy skipped," said Stermer. "We have focused on reporting child abuse, recording child abuse, responding to child abuse within 24 hours. We haven't focused on how to keep kids out of this river of terror that DCFS has become. At the moment I think it's of paramount importance to manage family preservation.

"Historically, the department has had two options [in cases of confirmed child abuse or neglect]: put the child in foster care or do nothing. We knew we could help the families if we had other tools in our menu."

The Chapin Hall evaluators are not ready to write off all elements of Family First. In an unpublished op-ed piece written after their evaluation was publicized,

John R. Schuerman and Tina L. Rzepnicki wrote: "It is clear that many families have benefited from the Family First program. The program provides a careful assessment of the needs of families, assessments that are more extensive than those DCFS is ordinarily able to make. . . . Some observers have suggested that the Family First program rewards irresponsible parenting by providing benefits to parents who abuse or neglect their children. . . . Parents do not abuse their children just to receive services. Many of the services of Family First should be available to many more families . . . ."

Joel Milner, a psychology professor at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, said family preservation efforts are worthwhile but are not suited to every case. "Philosophically I think that it's best to keep children in their families," he said. "On the other hand, I think one has to balance that philosophy against the risks involved.

Milner explains: "One philosophical view is that the family is the social base of society, and with that view there's a bias to put kids back in the family after abuse has occurred. But the child advocate view says, 'Just think of the child, not the system or the parents.' Philosophically I'm in complete accordance with the view of the family as a social base. But practically, I know there's a chance there's going to be some harm done [if an abusive family is preserved]. I don't like people taking one side or another. Let's not have an overriding philosophy. A decision should be driven by the individual case."

Which philosophical view prevails may depend on money.

"This is not the first time we've gone through a family preservation phase," Milner said. "We'll start getting into wanting families to stay intact at all costs when we don't have money for social services, when we don't have money for foster care. It seems like in tight economic times that's a goal. I'm not saying that's absolutely right, but if you study history carefully, it seems to bear out. We're not driven by clinical assessment;

we're driven by resources."

Jennifer Halperin

|

16/May 1993/Illinois Issues

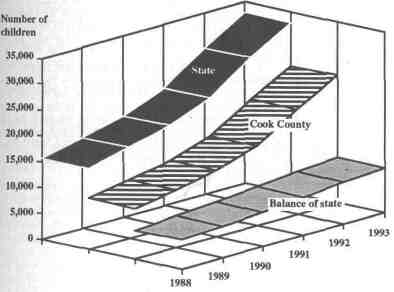

Figure 1. Children in foster care

Source: Department of Children and Family Services

|

was legal adviser for the state Board of Education and general counsel for the Department of Public Aid (DPA) before joining DCFS in 1991.

After moving from DPA to DCFS, "the thing that struck me was the difference in the bureaucracies," Ryder said, sounding pretty much like — well, a bureaucrat. "There were systems and organizations and structures for dealing with issues in place at the DPA. At the DCFS, what I saw was a system that was just trying to get through each day. And I say that seriously. It was crisis-oriented, always trying to address one crisis after another. Oftentimes the most basic casework decision becomes subject for the attention of everyone from the director of the agency right on down to the caseworker. We've tried in the last couple of years to make some progress on that score."

|

|

First and foremost on his agenda as director is complying with a consent decree that settled the B.H. v. Johnson lawsuit filed against the department in 1988 by the American Civil Liberties Union (see Illinois Issues, October 1991, page 16). The most talked-about element of the consent decree is a mandate to reduce the number of cases each DCFS caseworker must handle. The agency plans to hire 375 caseworkers by July 1 to meet the required case load ratio of 30 children or 25 multifamily children per worker; case loads in the Chicago area have run as high as 100 children per worker. The department then will seek to hire an additional 401 workers to meet another set of reforms that begins July 1, 1994.

|

'At the DCFS, what I saw was was a system that was just trying to get through each day. And I say that seriously. It was crisis-oriented, always trying to address one crisis after another . . .

|

These numbers raise another troubling query: Can quick hires of such large numbers yield quality employees? "Hiring a lot at once disrupts a lot," said child advocate Jerry Stermer, president of Voices for Illinois Children. "But our need is so great. We just have to bite the bullet and overcome those difficulties. The governor and the legislature have known the [consent decree] schedule since 1991, so we've had these many months to plan for this. It's worse than tragic that we let this come down to the wire and now will have to force feed the system." Ryder said the agency's efforts so far to hire the extra caseworkers have been "very encouraging." "There are minimum standards for the positions; we are not just hiring anyone," he said, adding that many social work graduates coming out of college now are promising candidates for the jobs, which require a bachelor's degree as well as DCFS training and successful completion of a DCFS-administered test. While relieving staggering case loads has garnered the most media attention of the B.H. consent decree stipulations, Ryder insists that its other requirements are equally crucial to the department's recovery. These include: modifying worker-to-supervisor ratios to reduce administrative personnel and increase the number involved with direct client service; setting up a comprehensive assessment system to identify children's and families' long-term needs so kids aren't shuffled from foster home to foster home indefinitely, and providing adequate health care to children in DCFS custody, from preventive measures to treatment for specific illnesses.

The B.H. v Johnson lawsuit revealed "massive, systemic problems at DCFS, and I think those problems grew up over a long period, and I think they're associated with the crisis orientation," Ryder said. "Management by crisis is not the way to do it. The consent decree lays out an agenda for child welfare reform in Illinois that I think is in many ways the

May 1993/Illinois Issues/17

most progressive and extensive of anything that has been tried in the nation. But it's something we have to do. We simply have to."

Stermer said he too sees the consent decree as "an important blueprint" for child welfare policy. "If we can meet these requirements, we'll have gotten a lot more accomplished than we've done in the last 10 to 15 years. Our group has been called an apologist for DCFS. We're not an apologist for them; we're just supporting an idea that will get us closer to where the public wants us."

As bound as DCFS is to follow the consent decree, not everyone sees the decree as the answer to the agency's problems. Patrick T. Murphy says it is the wrong approach to righting the agency's ailments, calling it "basically a sweetheart decree." As public guardian for juveniles in Cook County, he is probably the most ardent, vocal critic of DCFS, often feeding stories of its mishaps to Chicago reporters and then venting his outrage on the subject in newspapers' editorial pages via letters to the editor.

For instance, he said, instead of focusing on hiring more caseworkers for the agency, DCFS officials should weed out those workers who aren't pulling their load. "Every year we get more and more who can't do the job," said Murphy, who insists that AFSCME, the union representing DCFS caseworkers, protects incompetent employees from being fired. "DCFS should deal with the union problems, but they don't because the politicians cave in to AFSCME. AFSCME is the tail that wags the dog in that agency.

"Ryder's a nice guy but he's a lawyer, not a child welfare expert," Murphy said. "He's been a bureaucrat all his career . . . he's built to go along with what politicians say. What they should do is double the director's salary and get a real power expert in there who is used to dealing with real problems. They do goofy things over there. There are horrible social work decisions made by some goofy social workers. Morale is horrible. What you need is a real pro in there."

Murphy's criticisms are a thorn in Ryder's otherwise calm, soft-spoken demeanor. "I think there are a lot of mistakes made in child welfare, but I think there are people who have built careers out of misrepresenting those mistakes as the status quo," Ryder said, his voice rising in anger and frustration. "I get annoyed

with [Murphy], who I think has a responsible role to play. We should be working cooperatively, but he seems more comfortable attacking the agency. I'm sensitive to that because it hurts workers who are trying to do a good job. Whenever he's around everybody's mad at everybody. He's really working in the wrong area if he has political ambitions.

|

"In the articles you read in the newspaper [about DCFS caseworkers' errors] it sounds easy to have made a different decision," Ryder said. "In hindsight you've got 20/20 vision. But when you're the caseworker or the investigator and you're in that home looking at the situation and you have to make the decision to ... take custody of the child or risk keeping the child in that family with the potential consequences that can have if you've made the wrong assessment, that's really difficult.

"You have to be able to accept the fact, as unacceptable as it may sound, that there will always be that case where someone made that judgment call that is wrong and a child is abused as a result or a child dies as a result of not having intervened," Ryder said. "That possibility is always out there in these cases. On the other hand you can not justify on the basis of safety and child protection removing every child that you get a report on. So you've got to make a judgment call."

|

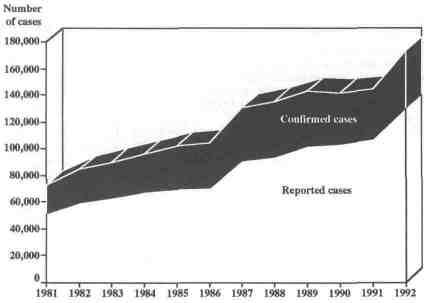

Figure 2. Reported, confirmed cases of child

abuse and neglect, 1981-1992

Source: Department of Children and Family Services

|

Taking issue with Murphy's assertions about the union's power is Roberta Lynch, associate director of AFSCME. "When you have an employee who clearly is not doing his or her job ... all you have to do is document what it is they're doing that's wrong," she said. "When we believe

18/May 1993/Illinois Issues

management has a case [against a union member], we do our best to help them resign and move on with his or her life.

"The problem in DCFS is that the workers are enormously overburdened," she said. "There's no literal way they could do everything they're supposed to do. The supervisors are too busy to effectively monitor what's supposed to be done. Until we get case loads down to a manageable level I'm not sure we can evaluate who is performing the way they should."

Another area of disagreement that arises in DCFS policy debates is over what drives child welfare laws. For instance, Ryder said child protection legislation too often is spurred by high-publicity instances of abuse or neglect. "A lot of times when you have a case that is notorious — that gets a lot of attention — it is apt to provoke some sort of legislative response." The "Home Alone" case, in which David and Sharon Schoo of St. Charles, Ill., vacationed in Acapulco late last year while their two young daughters were home without supervision is one example of a well-publicized (and presumably unusual) situation spurring proposed state legislation. "I don't think laws should be made that way," Ryder said. "You have to look at data, you have to analyze; I think you have to do some policy thinking and then make the call rather than make laws based on anecdotal, single occurrences."

Phelps said he agrees. "Government's nature — at least in modern times — is that we overreact and are crisis-oriented. Like with rats, if we see one problem, we think there must be 100 simmering below the surface," he said. "We overreact, and it's not just government. The press makes these situations more well-known. Then we have letters and phone calls, and some breed other ideas and solutions that cause expenses for government and taxpayers. It's human nature."

But Topinka sees it a different way. "Politicians are politicians and they always react to headlines. Our constituents get mad and call us, and we get mad and take it out on the agency. When I have a mother calling me about a problem in my district, don't talk to me about red tape — I've got a kid in trouble."

What one person sees as red tape, however, another sees as a legitimate problem. "Whenever you pass a bill and write another law in this area, you usually end up with unforeseen consequences," Ryder said. "Other aspects of children and families are impacted. Crises at this agency have driven legislative responses that have actually increased the number of children that we have reports on. For instance, the number of mandated reporters — people who are required upon criminal penalty to report — has affected us," bogging down investigators who are required by law to make contact with children reported as possible victims within 24 hours of the report. "I often think that serious cases involving a pedophile or a serious case involving a child seriously abused don't receive the attention they deserve from our investigators because they're so busy."

And yet just a week after Ryder made those comments in an interview, Cook County State's Atty. Jack O'Malley made a trip down to Springfield to tout a legislative package that included a proposal to add members of the clergy to the ranks of those required by law to report suspected child abuse or neglect. When asked about this difference of opinion on the matter, O'Malley said, "I haven't had a chance to talk to the new director, but if that's an accurate description of how he feels, I disagree very strongly. It seems a bit convoluted to me. The reason the caseworkers are overworked is that there is too much abuse going on ... not because there's too much reporting of abuse."

What is particularly disturbing about these child welfare disagreements is that the arguments and most players don't appear to be the stuff of typical Springfield battles. While political ambition may be a small motivating factor, most involved seem driven by a desire to better the state's system of caring for children whose own families may be unable to do so.

Contrary to what critics say, it seems that compliance with the B.H. consent decree is crucial not only because it is court-ordered but because it will help lay a more solid foundation than now exists for DCFS. The most common thread in and around the agency is frustration over workers' sheer inability to do their job. While large numbers of cases may not be the sole reason for this inability, they undoubtedly play some role; it seems easier to figure out and work toward logical solutions for problems in 25 to 30 families at one time than in 70 to 80.

Unfortunately, it seems there is no Utopian solution for the woes of DCFS — partly, say child welfare experts, because those woes are rooted in huge societal problems such as poverty, substance abuse, day care needs . . . not just an overburdened state bureaucracy. And what is crucial to remember in forming policy, they advise, is that the very nature of the family has changed.

"A single-parent family is more likely to have abuse occur — not because there's a single parent but because, those families tend to have fewer resources and a lower income, and there's more stress on the caretaker to take care of the kids," said Joel Milner, a psychology professor at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, who studies family violence. "Most people blame society for this, for not providing things like day care and equal pay for equal work. All these stresses from above are what causes [single parents] to act out against their kids."

Sumati N. Dubey, a professor at Jane Addams College of Social Work at the University of Illinois, Chicago, agreed that a lack of resources can drive a family over the edge. "I think single-parent families can do very well provided one thing — that they have strong economic resources," he said. "It becomes very difficult without it."

If Illinois is unable to make headway on these troubling issues that surround and promote family problems, it appears the assumption that things can't get worse for the state's child welfare system will be proved wrong.*

May 1993/Illinois Issues/19