By BEVERLEY SCOBELL

DCCA under Edgar

Is downsized agency

doing its job for jobs?

Photo by Chuck Stark

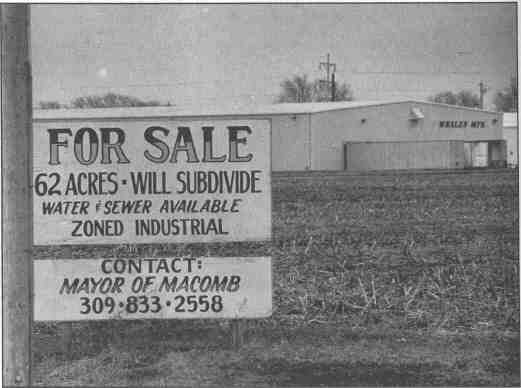

This industrial park in Macomb is in an enterprise zone, with some benefits administered through

Photo by Chuck Stark

This industrial park in Macomb is in an enterprise zone, with some benefits administered through

DCCA. Mike Beaty. executive director of Macomb Area Development Corporation that markets the acreage, says the

corporation offers the space at $7,000 per acre with the incentive of a $500 per acre "write-down" for every job

created. In the last year and a half, Beaty reports, over 100 industrial jobs have been created in the Macomb area.

"Millions of jobs are disappearing from the U.S. workforce, and these jobs won't be coming back," states Jim Egan, president and CEO of Mueller Company in Decatur. "Our whole way of doing business is changing," Egan believes. "We are experiencing a metamorphosis, a total restructuring of corporate America." If we are indeed in a second industrial revolution as he and other company CEOs believe, the question for Illinois becomes:

Can governmental leaders guide us through it so that citizens experience a quality of life better than they now have? To most people, quality of life relates directly to job security.

The Department of Commerce and Community Affairs (DCCA) is Illinois

state government's arm responsible for job stability and growth through economic development, but is it effectively using taxpayers' dollars to that end? Can a state agency, itself in the midst of restructuring after deep cuts in staff and budget, keep pace with the changes?

Gov. Jim Edgar's answer is that job creation and economic development cannot be the sole responsibility of

government or of one agency. "Government must take a leadership role in bringing together the various constituencies to impact business, work force and community development," says Edgar. Last year Edgar implemented this philosophy for DCCA and fulfilled his campaign pledge to downsize and streamline the agency. DCCA's general revenue fund budget was slashed from $93.1 million in

20/May 1993/Illinois Issues

fiscal year 1992 to $27.6 million in fiscal year 1993 (other funding sources stayed relatively stable at $439.3 million in federal funds and $156.6 million from other state funds for fiscal 1993). DCCA's work force was cut from 618 to 407. In fiscal year 1988, DCCA had a budget of $592 million plus $399 million in federal funds and $128.5 million in "dedicated revenues," such as the hotel tax that funds tourism. "The agency was administering more than 70 diverse programs and was trying to be all things to all people," Edgar says. "There was no clear-cut mission."

Jan Grayson, director of DCCA, agrees that the agency under former Gov. James R. Thompson followed a different philosophy. "DCCA tended to operate somewhat autonomously," says Grayson. "It tended to be the dictator as opposed to the partner and tended not to take advantage of the growing resources that were there locally."

willingness to cut their appropriation last year."

But administration officials disagree. Director Grayson reiterates Gov. Edgar's position: "The government doesn't create jobs; businesses create jobs." DCCA, Grayson claims, is no longer subsidizing a few large companies, but rather it is expending its energies and resources to help businesses help themselves. The expected outcome is greater economic activity and more jobs for Illinois workers. "Today," Edgar explains, "DCCA's programs and services are geared toward work force development, expanding export trade, creating a climate conducive to business development and community revitalization."

Top job counties in Illinois, 1991

Illinois had 4.3 million jobs in 1991, as

measured by the Illinois Department of

Employment Security. The top 14 counties

in employment contained 3.56 million jobs,

or 83 percent of the state's total. The other

88 counties, each with fewer than 50,000 jobs,

accounted for just one in five jobs statewide.

|

COUNTY % of 1991 state JOBS |

|

Cook 50.4 2,184,182 |

|

DuPage |

9.0 |

392,130 |

|

Lake |

43 |

186,986 |

|

Kane |

2.7 |

118,548 |

|

Winnebago |

2.6 |

111,583 |

|

Peoria |

1.9 |

82,348 |

|

Will |

1.8 |

78,010 |

|

Madison |

1.6 |

71,518 |

|

Sangamon |

1.6 |

69,956 |

|

Rock Island |

13 |

57,657 |

|

St. Clair |

13 |

57,501 |

|

Champaign |

13 |

54,383 |

|

McHenry |

1.2 |

51,975 |

|

McLean |

1.2 |

51,824 |

|

It is difficult — and some economists argue impossible — for any one arm of government to have an effect, lest it be negative, on the tides and fortunes of businesses. There are simply too many factors beyond government's control. University of Illinois economist John Crihfield criticizes government's role in job creation "stimulus" programs. "Few of the federal or state programs would pass a cost/benefit test," asserts Crihfield. "There's a lot of money here [in the proposed $16 billion federal stimulus package before Congress in early April] that cities and towns would love to have because they can't raise it themselves and the big sugar daddy in Washington is willing to send [it]." One example, he says, is $12.8 million for a city in California for a civic center expansion. The private sector, he suggests, won't support civic centers in general because it considers them boondoggles. "That's the same thing they've been doing here in Peoria and the Quad Cities," says Crihfield. "If the private sector won't fund it, go to the government. Political processes will give it to you. Pork barrel."

Crihfield does not believe government grants create jobs. "You're taking them from Point A and putting them in Point B. There's no job creation there; it's just shifting stuff around." In addition, Crihfield doubts that DCCA is all that different from what it was in its heyday under Thompson. He feels DCCA policymakers have simply changed the names of some programs. "They are still basically an all-things-to-all-people department," says Crihfield. "There is still no clear-cut mission. They are just doing what they've always done with fewer people and less money."

|

May 1993/ Illinois Issues/21

Jan Grayson disagrees. Because DCCA lost 70 percent of its budget and over half its people, it has been forced to focus its efforts on what will help the Illinois economy the most while using DCCA resources the least. "Our efforts rely heavily on outside resources, public and private partnerships," Grayson says. "We are focusing on wholesaling our services, working with groups rather than individuals."

One of the new objectives is to group services into "clusters" of businesses that supply products to large equipment manufacturers like Caterpillar and Deere, agriproduct giants like Archer Daniels Midland and Staley or coal mining operations like Peabody and AMAX. DCCA has identified 12 clusters in the state.

Norm Sims, DCCA's manager of policy, development, planning and research, says the overall economic development strategy is pretty simple: Sell as much goods and services as possible outside of Illinois and, in order to lower their costs, provide producers in the state with access to as many Illinois suppliers as possible. "The more we tie them together, get them working together on products, the stronger they become," explains Sims. DCCA's primary objective to help businesses to grow, expand and stay in Illinois is twofold: Support them in training and retraining an already good work force and by tunneling federal grant money to communities to build and upgrade infrastructure. Grayson also thinks the agency should take part in administration policy decisions facilitating access to capital and new technologies and formulating "pro-competitive" state tax and regulatory policies.

The cluster policy extends to job training, a sizable component of the Edgar administration's strategy to form public/private partnerships to keep jobs here. The theory seems to be that if the state, and particularly DCCA, can help businesses, large and small, stay at the technological edge of product development and delivery, they will produce at the high quality and competitive cost levels demanded of the marketplace and thus have no reason to leave the state and dislocate workers. Since statistics show that most growth is in small and medium-sized businesses (under 500 employees), DCCA is targeting those businesses for training grants.

The Industrial Training Program (ITP) administered by DCCA is the primary tool used toward that goal. It trains workers on the job in existing industries. Scaled back nearly 18 percent, from $13 million in fiscal year 1992 to $10.7 million in fiscal year 1993, ITP, like the rest of DCCA, has had to redirect its resources.

Contracts to large manufacturers like Caterpillar and Deere are now targeted to serve smaller companies that supply the equipment manufacturers and often have just a few employees in need of specialized training. Jerry Wright, who manages the training program for Caterpillar in Peoria, says that he has received only positive feedback from supplier companies that have taken advantage of multicompany training through the DCCA grant. "They are typically single-owner companies with fewer than 50 employees," says Wright. "They wouldn't be able to afford the training

on their own, but with the training we can offer them because of the ITP grant they are able to stay productive." ITP-subsidized classes through Caterpillar range from training in technical skills to people skills.

Renishaw Inc. in Schaumburg sent six employees to the ITP/Caterpillar cluster training. Employing 50 people to service, repair and distribute the electronic measuring devices manufactured at the parent company in the United Kingdom, this company could not afford the training on its own. Tony Szewczyk, service manager for Renishaw, says the computerized machining training costs more than $1,000 per employee. "That amount is difficult to budget in these times," says Szewczyk. He says three employees have advanced their positions in the company because of DCCA-subsidized training provided through Caterpillar.

One small business that did not fit into the mold was Automation International, a specialty machine shop in Danville that produces customized machines for other manufacturers. It is a new business that employs 47 people. It sought help from DCCA for training funds because its craftsmen must be very skilled to do the individual machining tasks. Full training through its in-house apprenticeship takes up to four years.

Verna Quick, the company's human resource manager, says Automation International's unique product prevents it from "clustering" with other machine shops. "That's the problem we ran into," says Quick. "There is no other company in town that could match our needs, that we could be grouped with." Quick does not agree with DCCA in putting the majority of the training money into group training. "I didn't think it was fair to the smaller companies who can't join in with larger companies or medium-size companies to get the training. There was no hope for us to get any of that money at all, and we could have really used it during our slow time," says Quick. She says when the company couldn't apply for the group grant, it had to go with the individual grant, where there is very little money.

Ruppman Marketing Technologies in Peoria received an individual grant to train operators to answer 800-number telephone calls, referring questions/comments from customers to dealers listed with the service. CEO Charles T. Ruppman Jr. confirms that technology-driven industries are among the fastest growing in Illinois. In 1963 he started with 28 employees and expects to employ more than 1,000 by the end of the year. Ruppman uses DCCA training money to help pay for up to six weeks' training for each new worker he is hiring. He says the jobs are entry level, but the training allows workers to quickly move into the $ 10 to $ 12 per hour range. "In addition," says Ruppman, "when employees leave here to go to other jobs in the area, they are readily hired because other employers know they have had good training." He says he has 20 people in training at all times.

One large company, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, was denied an ITP grant to train 100 employees added when it built a new customer service facility in Danville. Austin Waldron, director of claims administration, says the company was counting on it, but not getting the grant did not stop the building and the expansion of the work force. "We're a big

22/May 1993/Illinois Issues

organization," says Waldron, and as such not as dependent on government grants as some companies might be.

Not every company is eager for DCCA help. Jim Egan of Mueller Company in Decatur, which manufacturs flow control valves and other equipment for gas and water distribution systems, did not seek DCCA grants for retraining in his company's move from assembly line to cell manufacturing. "I guess I have to plead ignorance," says Egan, "but in all honesty when I get something from the state or federal government, it's usually always bad news." He says the company would rather train workers on its own than have to work within government programs.

Yet what's happening at Mueller's proves two points about jobs in Illinois. One, with or without government subsidies, jobs are shifting from one place to another (the 1993 Harris Michigan Industrial Directory reports a 31 percent shift of companies within Illinois' boundaries in the last five years). And two, a highly trained, skilled work force will keep the jobs in Illinois.

Mueller Company recently bought Rockford Eclipse Inc., a manufacturer of meter valves and meter bars, and will transfer the technology to its Decatur plant. Nearly 80 jobs will be lost in Rockford, but those jobs will be saved in Decatur. Modernization at the Decatur plant that created floor space to allow the company to expand its gas products division also could have created layoffs. But those jobs lost in Rockford and saved in Decatur could have left the state entirely. CEO Egan explains the Rockford technology could have gone to other plant locations of the parent company, Tyco Laboratories, in Kentucky, Tennessee or Arkansas. The jobs stayed in Illinois because of the work force in Decatur. "The difference in the level of skills of our craftsmen in the Decatur plant," says Egan, "outweighed the cost of power, workmen's compensation and other costs that were lower in those other states."

To keep jobs in Illinois, Grayson thinks it is important to keep up a technologically based, productivity based economy. Admittedly, that means modernization that often translates into job loss. "That job loss in itself," says Grayson, "even though it is discouraging and [something] we would want to avoid, if it in fact saves the jobs that remain due to the fact that the company becomes competitive worldwide, you have to look upon it as a positive factor."

Dan Cosgrove of the Illinois chapter of the AFLCIO does not agree. "The general opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement [NAFTA] has been that companies will move jobs there simply for lower wages, and that will happen," says Cosgrove. He concedes there may be some other jobs produced in Illinois. But even if the people who predict there will be more jobs in the long run are right, "we are not willing to make cannon fodder out of all the people who will be disrupted," says Cosgrove. However, he predicts that the job loss is not going to be mainly union members. "It's going to be mainly middle management people. That group of people is beginning to realize that . . . the organization to which they devoted 30 years no longer has any use for them. And they thought that their organization would only do that to the blue-collar union members."

For companies that want DCCA help, training grants offer the opportunity to expand into foreign markets. Zenith Cutter Co. in Rockford is an example. This privately owned manufacturer of machine knives (used in the manufacture of corrugated boxes and paper and in the recycling of plastic and wire scrap) employs 160 people. It is receiving $70,000 of a $1 million DCCA/ITP grant given to the Illinois Manufacturers' Association and the Management Association of Illinois to train a projected 7,700 workers across the state. Cedric Blazer, president and CEO of Zenith Cutter, says his company will use its share of the funds to train workers in total quality management (TQM) techniques and in procedures to meet ISO 9000 requirements. ISO 9000 is an international quality standard.

That standard is key to expanding in foreign markets where Zenith Cutter now exports 7 percent of its product. Blazer says an ISO 9000 certification for a manufacturing business is comparable to a UL stamp for an electrical product or a Good Housekeeping seal of approval for a food product. His company is scheduled to show its product at an international show for box makers in Paris, France, next year, and he needs ISO 9000 certification in order to be

May 1993/Illinois Issues/23

Photo by Don Norton

The existing plant of Carbondale's largest manufacturer, the German-based firm of tesa tuck, inc., is pictured above. It will be retrofitted as a business incubator after the company's new facility is built in Carbondale. Employing 350 people with projections to add more jobs, tesa tuck will receive up to $525,000 in ITP grants for training workers on state-of-the-art equipment at the new plant. According to Donna Foy, executive director of the Carbondale Business Development Corporation, DCCA awarded nearly $1.8 million in grants and low-interest loans to keep those jobs in Illinois. |

qualified to sell in the European marketplace. Blazer reports that more of his customers are ISO certified and are requiring their suppliers to be certified also.

DCCA sees exports as the key to job creation in Illinois. "Export is a job creation environment," says Grayson. "Almost all growth in the last 10 years has been through exports." In an admittedly unscientific survey of 250 Illinois manufacturing companies, DCCA researcher Jeff Hamilton reports finding only 12 percent were exporting. "The need is to broaden that base dramatically," concludes Grayson. He says that many companies, some with just a handful of employees, either think they are too small to export or they don't know what it takes to export. He says programs directed by DCCA point out to small and medium-sized businesses the opportunities in exporting and give them information to get them over barriers.

|

Exports, as well as other services, are coordinated through the 26 Small Business Development Centers (SBDCs) directed by DCCA and partially funded by the federal Small Business Administration (SBA). DCCA and the SBA work in conjunction with higher education and the private sector to offer counseling (business plans, financial matters, technical assistance), training and research help for those people with an idea for starting a business. They offer help with exporting and expansion of mature companies. Mitchell says that over the 10-year period the SBDCs have been operating, 27,713 client-verified jobs have been created and 33,622 have been retained. DCCA does not keep records characterizing the kind of jobs that were created, but say they run the gamut from technical to production.

Within those centers are two specialized services: one that helps companies apply for federal, state and private grants; and another that helps companies, particularly those that have never before exported, learn how to sell their products internationally. The first service is extended through 16 Procurement Assistance Centers located within SBDCs around the state. Mitchell reports that the centers have assisted companies in obtaining 8,545 federal contracts worth $742 million. The second service is offered through three International Trade Centers (a fourth for Chicago and Cook County was proposed in Gov. Edgar's 1994 budget). The International Trade Centers, created just three years ago, have helped businesses obtain $23.6 million in export sales. Mitchell says that a national study showed that for every dollar contributed to SBDCs by the government, $18 was returned to tax coffers.

The focus on helping more little guys and gals instead of a few big ones is a change of philosophy at DCCA, and a reflection of a changing society. The trends in jobs in Illinois — where and what kind they are — indicate what everyone is seeing around them, that people just graduating from high school or college are going to work in a different world. All studies show a shift from a nation — and a state — of manufacturers to one of service providers. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that by the year 2000, four of five jobs will be in fields such as health care, education, retail, wholesale, banking, government and real estate.

A DCCA study conducted by SRI/DRI McGraw-Hill reports that the slowest growing occupations in Illinois through the rest of this decade will be farm operators/managers, followed by assemblers and other handworkers and material-moving equipment operators. The fastest growing occupations will be retail salespersons, registered nurses and other protective care workers, accountants and auditors, and general managers and top executives.

The Illinois Department of Employment Security (IDES) reports that in 1991 of the 4.3 million jobs covered by the Illinois Unemployment Insurance Act, 3 million, or 70 percent of the state's total, were located in Cook and its five collar counties of DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry and Will. Manufacturing still accounts for nearly one million workers (21.9 percent), but the service industry accounts for nearly 1.3 million jobs (29.3 percent). The next largest segment, retail trade, accounts for 20.3 percent of the work force, or nearly 900,000 jobs.

DCCA also administers job training programs from the U.S. Department of Labor. The Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA) trains unskilled or unemployed adults for entry or reentry into the job market. Individualized programs also retrain dislocated workers (due to layoffs or plant closings) and older workers (age 55 and older). In fiscal year 1992 more than 22,000 workers were retrained. JTPA also has a summer program that gives work experience and academic enrichment to disadvantaged youth. That program served nearly 40,000 young people last fiscal year. In total, in fiscal year 1992 federal funds of over $173 million prepared

24/May 1993/Illinois Issues

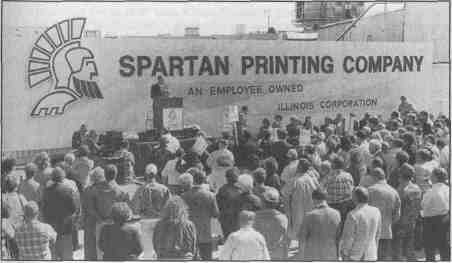

Photo by Mike Springston, Sparta News-Plaindealer

Photo by Mike Springston, Sparta News-Plaindealer

This crowd gathered last October in Sparta to celebrate the purchase of Spartan Printing Company by its employees. Ed Crow, economic development director for Randolph County, says a $25,000 grant from DCCA was instrumental in helping the 1,100 employees buy the plant from World Color Press, a speciality printing firm that used to print DC Comics and other comic books. The DCCA grant, Crow says, acted as "seed money" to get the community involved and raise other capital.

|

nearly 100,000 Illinoisans for work.

Gov. Edgar's 1994 budget request for DCCA includes $180.3 million for JPTA, which reflects a $31.3 million drop from 1993 levels that were boosted by a onetime federal youth employment allocation. The ITP appropriation request is increased by $241,200 for a total of $11 million.

So is DCCA doing its job in helping Illinois businesses expand and add jobs? Economist Crihfield thinks not. "DCCA has been criticized in recent years for subsidizing big business in Illinois," he says. "Why should it now subsidize small business?" asks Crihfield. "Basically, they push programs that are often bad public policy. They use taxpayers' money to benefit politically favored groups and distort decisions by private investors."

|

Companies surveyed report mixed reactions to DCCA's efforts. Cedric Blazer is glad for the help his company is receiving, but he reports he would give his employees the training with or without the DCCA grants. So reports Austin Waldron, Verna Quick and Charles Ruppman. They all say, "Training is an ongoing process. It is what keeps us competitive." Yet for companies like Tony Szewczyk's a small amount of DCCA training dollars can make a difference in the productivity of employees.

Blazer worries more about not being able to expand and add jobs because of the limitations new taxes proposed by the Clinton administration will cause for his company. "By increasing taxes they're going to reduce the amount that can be invested and spent on new equipment in companies like ours," says Blazer. "That's why we've had an aggressive growth program, expanded our plant and continually added new people." He says more taxes will prevent him from adding new equipment to put new people to work.

|

Changes in the job market have occurred, but Blazer thinks most people don't understand the change. "When they talk about business, everybody thinks about General Motors, IBM and General Electric, and they forget that business is a whole lot of people like us all over the country hiring people. When 5,000 Zenith Cutters hire 10 people, nobody says a word. But when IBM lays off 5,000, the whole world knows about it."

In this time of change — evolution, if not revolution in the job market — people are looking to their leaders for some sense of job security, some sense of balance between what has been and what is to come. That can effect

elections. People secure in their jobs tend to vote for incumbents. People worried about their jobs tend to vote for a change. Whatever DCCA can do to put more Illinoisans to work and make those with a job feel more secure may make the difference next year in whether or not Gov. Edgar, like George Bush, joins the ranks of the unemployed.*

|

Photo courtesy of Knoblauch Studios

Photo courtesy of Knoblauch Studios

Blue Cross/Blue Shield in Danville hired 100 new employees when this new customer service facility was completed last year. Jeff Fauver, executive assistant for the Danville Area Economic Development Corporation, reports that in the past 18 months private industry in the area has created 775 permanent new jobs, with the expectation that one company will add another 150 jobs over the next two years. Fauver says that it appears the 1,200 jobs at the General Motors foundry will be retained under new ownership, but its future is still being negotiated.

|

May 1993/Illinois Issues/25

|