|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

STAYING ALIVE

FOR ILLINOIS' SMALL TOWNS,

SURVIVAL MAY SIMPLY BE ANOTHER WAY OF DYING

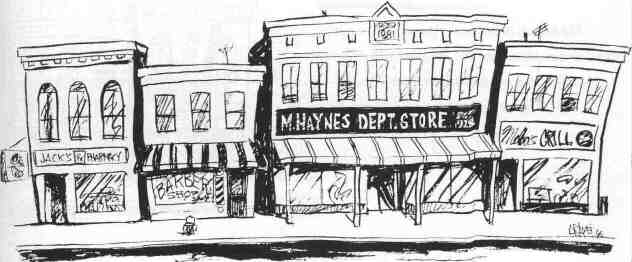

Story by Karin Admiraal • Illustration by Mike Cramer

At 79, Dean Lindholm has lived and worked all his life in Sibley. He's the exception: Most people leave when they graduate from high school. And those who stay must look elsewhere for jobs.

Once a prosperous farming community in Ford County, Sibley — with a population of 368 — has little business or industry. These days the tiny central Illinois town is struggling just to survive.

But Sibley is typical of many towns with fewer than 5,000 residents. Since paved roads and automobiles made travel between cities easier, small towns have been losing business. And the loss of commerce means a loss of population, as people follow jobs to the cities and suburbs.

In fact, towns and rural areas make up a smaller percentage of the country's population than they did just 15 years ago. Between 1980 and 1990, the U.S. population in cities and suburbs grew by almost 15 percent. In nonmetropolitan areas, the growth was much slower — only 4.5 percent.

In Illinois, a state where 85 percent of the people live in cities, the contrast is even sharper. Metropolitan areas grew, while the state's rural areas and small towns lost almost 6 percent of their population. Of the 74 nonmetropolitan counties in Illinois, 70 lost population between 1980 and 1990, according to Norman Walzer of the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs in Macomb. The same was true throughout the country, as factories closed and timber, mining and farming production slowed.

Still, the 1990s have brought a partial reversal for small towns. Between 1990 and 1995, population grew in 47 rural Illinois counties. Walzer attributes this gain in part to people moving from cities to the surrounding small towns while continuing to work in the cities. Though the future may seem brighter for small towns, the economic pressures that prompted people to leave still exist. Survival will depend on adaptation. But inevitably, there are trade-offs.

Sibley and two other central Illinois towns illustrate different ways this state's small towns are attempting to cope with economic and social change — and the challenges they face as a result. Tuscola, a town of 4,155, is trying to boost its economy through tourism. Mahomet, with 4,200 residents, has become a bedroom community for the Champaign-Urbana metropolitan area. But towns that can't attract tourists or commuters could disappear altogether. That's the danger facing Sibley.

Sibley got its start in the late 19th century as an 18,000-acre farm owned by the Sibley family. But the town that began as a huge family farm is now threatened by the rise of corporate farming. Today, only about 2,800 acres of the land surrounding the town still are owned by Sibley descendants.

When Dean Lindholm and his wife, Gwen, started farming for the Sibleys in 1947, their farm was 320 acres, about the average size in that area at the time. When the first Hiram Sibley owned the land, his estate supported 146 families. The farmers provided business for three grocery stores, two churches and several country schools. Sibley's main street used to boast a barber shop, a cafe, a movie theater and a meat locker. At one time, the town supported an International Harvester dealership and a lumber yard.

"Those little businesses got squeezed out," says Lindholm.

Today, few farms around Sibley are smaller than 1,000 acres. Farmers use machines that allow one person to plant and harvest as much as 10 of the original Sibley farmers could. So the land can support far fewer families, which means fewer people to patronize Sibley's businesses.

At the same time, farming itself has become less important to the American economy. High-tech manufacturing, information industries and business services have tended to concentrate in cities and suburbs. That, according to a 1993 article by

22 / February 1997 Illinois Issues

William Galston, then with the White House Office of Domestic Policy, has left small towns with higher unemployment rates, lower incomes and higher poverty rates than metropolitan areas.

In addition to a changing economy and the trend toward larger farms, Sibley and other small towns have been changed by advances in transportation. With cars and paved roads, people can travel farther to shop. Lindholm remembers that when he was young it was a special occasion to leave the farm and go a few miles into town. Now, he and Gwen think nothing of driving nine miles to Gibson City for groceries, or even 40 miles to Champaign or Bloomington to shop for clothes.

So people who live in and around small towns are not necessarily dependent on local business. Instead, they can go where the selection and prices are best. And that tends to be the WalMarts, Kmarts and other "superstores" that crowd the edges of larger cities.

The loss of jobs and services leads to the biggest problem for small towns: a loss of people. Neither of the Lindholm's two children stayed in Sibley, a situation that has been common in the town for years. Lindholm says that of his high school class of 17, only a few stayed in town after graduating.

Some Sibley residents are trying to combat the town's downward trend. In 1993, they formed the Sibley Business and Historical Association to revitalize Sciota, the town's main street. Part of the inspiration behind the association was Krista McCallister, who in 1990 bought the old Sibley train depot and turned it into a Victorian gift shop.

Since McCallister opened the Depot, other businesses have sprung up along Sciota, including an antique shop, a cookware store, a photographer and a small factory. Still, McCallister admits, there's not much in Sibley to attract tourists to the town's shops. "To get people in the door — that's the biggest challenge," she says. "Once we get people in, we do pretty well."

Although McCallister is optimistic about her town's future, Sibley has had to adapt to the changing economy: consolidating its schools, losing some businesses and forcing residents to look in neighboring towns for jobs. At 28 miles from Interstate 74, and 24 miles from Interstate 57, Sibley is too far from most cities to serve as a bedroom community. Its future may depend as much on the loyalty of families like the Lindholms as the willingness of folks to drive farther to visit gift shops like McCallister's.

But 28 miles south of Sibley on Highway 47 is a town whose location has given it a very different look. Mahomet sits at the intersection of Interstate 74 and highways 47 and 150. It's an easy 10-mile drive to the hospitals, university and other employment and shopping opportunities in Champaign. And the ease of that commute has shaped Mahomet during the past 50 years.

Beyond a short strip of gas stations and restaurants and a main street with a few specialty stores, Mahomet is a residential town. Families seeking to combine good jobs and city conveniences with small-town living have descended on Mahomet in droves. In 1950, Mahomet's population was 1,017. The town grew steadily, and by 1980 had almost doubled. By 1996, the population had almost doubled again. And the growth shows no sign of slowing. Village Administrator Steven Wilke predicts that within 10 years, Mahomet's population will have reached 10,000.

Mahomet, which was once a typical Illinois farm town much like Sibley, has become a suburb of Champaign. What has happened in Mahomet is similar to what has happened all over the country to small towns close to larger urban areas. Walzer of the Institute for Rural Affairs says that since 1980, many people have moved out of metropolitan areas, an out-migration he calls "urban spillover" from cities

Illinois Issues February 1997 / 23

|

Mahomet's booming population gives that town a more secure future than others. But there's a trade-off in growth — the potential loss of a close-knit and coherent community. |

|

into the surrounding rural areas. (While many people have moved into rural areas, more have moved into metropolitan areas, so there is a net gain in the cities.)

Mahomet's booming population gives the town a more secure future than Sibley's. But there's a trade-off in growth — which University of Illinois human and community development professor John Van Es says is the biggest change in small towns — the loss of a coherent community.

The expectation for a small town, says Van Es, is that everyone will know one another, share common values and feel a sense of security. But in a rapidly expanding town, that feeling is difficult to maintain. "People have a much more fragmented existence with one another than they did before," he says. "They work one place, shop somewhere else."

Mahomet resident Pam Iverson is a good example of that trend. Because she and her husband both work in Champaign, it's convenient for them to patronize the stores there as well. Iverson says most of her friends are outside Mahomet, too, people she's met at work. Still, she says she's found Mahomet friendly and welcoming.

But to some residents, especially those who are older, Mahomet is no longer a close-knit community. "It's not like it was," says Robert Clapper Jr., who has lived in or near Mahomet for all of his 71 years. "You spoke to everyone and it was polite. Now you just go about your business."

While older residents miss the closeness and "neighborliness" of living in a town of 700 people, that kind of community may not be possible in a town of 10,000. "You want to remain a small community," says Wilke. "We've worked really hard to maintain that feeling, but we're really a big community."

Farther south of Mahomet, in Douglas County, Tuscola also faces the challenge of maintaining its identity as it tries to boost its economy by attracting tourism.

During the first week of June, almost every downtown Tuscola business displayed a sign welcoming cross-stitchers. The cross-stitchers were in Douglas County for their show at Rockome Gardens, south of Tuscola. They were in town to visit the Country Sampler. Inside the store, a cross-stitched welcome sign greeted customers. Kits to make cross-stitched magnets, hats, Christmas ornaments and old-fashioned samplers lined the walls. T-shirts with slogans like "cross- stitch fever — catch it" were stacked on one shelf. And pattern books for counted cross-stitch designs were everywhere.

The store is owned by three local women, Betsy Stuerke, Dee Beachy and Carol Weemer. Since they opened the shop 12 years ago, they've moved three times, each time adding more space and merchandise to meet the demand. "In our very narrow specialty, we have offered everything there is, and people come from all over," says Stuerke. The shop recently got a letter from Italy ordering supplies. Most customers don't come from that far away, Stuerke says, but people often drive the 150 miles from Chicago to visit the store.

Small towns are counting on drawing such people. It's part of what University of Illinois leisure studies professor Daniel Fesenmaier calls the "theme-parking" of small-town America.

Towns, says Fesenmaier, are turning themselves into products, making a commodity of the quaintness many associate with rural America. Fesenmaier says several small towns in southern Illinois are creating antique malls. In northern Illinois, towns are promoting themselves as part of a "chocolate trail." Tuscola is billing itself as "your first stop in Illinois Amish country," drawing on the already established popularity of towns like Arthur and Arcola, which are also in Douglas County.

In the 44 years he's lived in town,

24 / February 1997 Illinois Issues

|

|

Tuscola's success has had its costs. Some residents worry that the focus on development has led to neglect of other aspects of town life. |

attorney Raymond Lee has seen Tuscola change from a small farm town, whose main business was county government, to a specialty market for tourists. "The people who have been successful in this community have specialized and done it in a big way," Lee says. "People want to come to the country and buy a trinket."

And there are plenty of places to do that in Tuscola. The traveler entering town from 1-57 is welcomed by the Factory Stores, an outlet mall with almost 60 stores. Local officials expect more construction at the mall soon. In addition to the Country Sampler, downtown Tuscola has shops offering antiques, dolls and furniture. And the Douglas County Museum, also on Main Street, attracts visitors from all over Illinois, most other states and even other countries.

But Tuscola's economic success has had its costs. Some residents worry that the focus on economic development has led to a neglect of other aspects of town life.

Lynnita Sommer, director of the museum, says most of the town's historic structures have disappeared over the years. Sommer cites a nearly 100-year-old railroad control tower that was torn down about the same time the outlet mall came to town. "The city council was busy concentrating on the mall, so the tower went down." But the main economic development problem for small towns like Tuscola is keeping the money in town. Large businesses with absentee owners may drive out smaller, locally owned operations. While factories and malls provide jobs for local people and taxes to support city services, a large part of the profit leaves town and goes to the corporate headquarters. The outlet mall, for example, is owned by an Ohio retirement group and managed by Charter Oak Partners in Vienna, Va. Although the mall employs more than 400 area residents, many of the jobs are part-time and low-paying.

Fesenmaier says loss of local control is a problem for many successful tourist communities. Galena, Traverse City, Mich., Door County, Wis., and Brown County, Ind., are all examples of rural areas that have lost control of their economic life. In Brown County, for example, Fesenmaier says 80 percent of the tourism business is owned by outsiders, mostly by people in Indianapolis. "We tell people their goal should be to be less successful than Galena or Brown County," Fesenmaier says.

In Tuscola, the Country Sampler and other Main Street businesses are all still locally owned. In spite of the mall, the town has not yet become a Galena or a Brown County. But its future, like the future of all small towns, remains uncertain.

As Sibley, Mahomet and Tuscola demonstrate, any choices small towns make have costs. The smallest, least-connected towns may have the easiest time preserving a sense of community and identity without interference from the outside world. But they remain isolated at the risk of dying out completely. For growing towns like Tuscola, and especially Mahomet, the cost of economic survival may be the death of community, at least the kind of community some residents remember.

But some experts say the sense of community is what small towns need to focus on to attract residents and stay alive.

Kenneth Munsell is the director of the Small Towns Institute in Ellensburg, Wash. He says he sees a longing throughout the country for community connection. Even in suburban developments, people are trying to build community centers, places where they can meet and get to know one another.

"Those places are becoming popular because we're beginning to realize we've lost that," he says. "That's the strength of small towns."

Karin Admiraal, a former central Illinois resident, is a free-lance writer who now lives in Kentucky.

Illinois Issues February 1997 / 25

|

|