|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

LET MY

PEOPLE

GO

A march passes through a local neighborhood on 12th Street, January 1969.

28 / February 1997 Illinois Issues

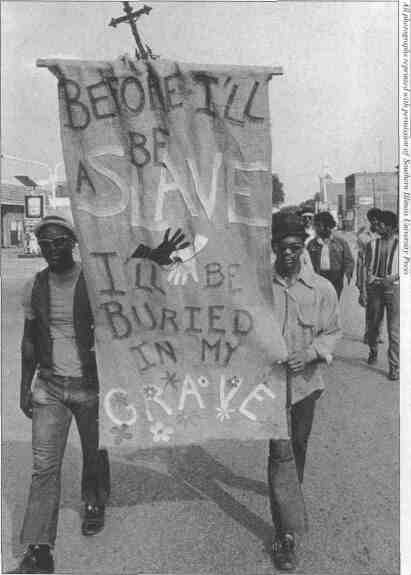

Marchers with the banner that became a symbol of the Cairo civil rights movement.

This photograph was taken in downtown Cairo in July 1969. Left: Wade Walters; Right:

Clarence Dossie.

CAIRO, ILLINOIS • 1967-1973

Civil Rights Photographs by Preston Ewing Jr.

Edited by Jan Peterson Roddy

Published by Southern Illinois University Press

Illinois Issues February 1997/ 29

Reviewed by Gary Hart

In 1967, Robert Hunt, a 19-year-old black soldier, took a leave and returned to his home in Cairo. On July 15, he was found hanged in the Cairo police station. City officials called it suicide. But protesters took to the streets and the subsequent riots lasted three days. Cairo's black community then organized a battle for economic and social justice that spanned seven years.

|

Let My People Go recounts the struggle through pictures taken by Preston Ewing Jr., who was president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People's (NAACP) Cairo chapter at the time. The book, published by Southern Illinois University Press, was released recently. Cairo, on the far tip of the state, is located at the intersection of Kentucky and Missouri, where the Ohio River meets the Mississippi. Its roots have always reached south. In 1820, approximately 20 slaves helped erect the first buildings. Later, escaping slaves crossed the river there. Some followed the river system north, some managed to secure secret rail passage to Chicago and some stayed on in Cairo. In the early 20th century, African Americans continued to migrate to Cairo from the south. By 1960, they made up 39 percent of the population. Meanwhile, up through the 1950s, whites enforced strict segregation, though it was prohibited under Illinois state law. Yet, the movement for civil rights got an early start in Cairo. A local chapter of the NAACP was organized |

|

in Cairo in 1918. In the 1940s and 1950s activists won equal pay for black teachers and public school integration. In the early 1960s, they made gains in ending segregation in movie theaters and restaurants. But Robert Hunt's death was a flash point. The marches, boycotts and court battles that it sparked lasted until 1973.

The photonarrative was edited by Jan Peterson Roddy, who teaches in the Department of Cinema and Photography at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. Ewing, a native of Cairo, continues to collect and take photographs to enhance the historic collections he's compiling. These collections will become part of the Ewing/Kendrick Museum of Black History, slated to open in Cairo in the near future.

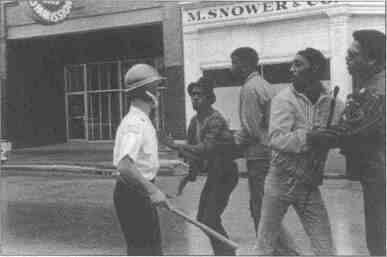

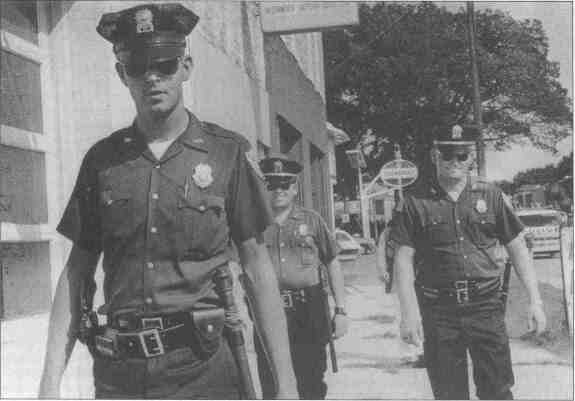

The documentary images of the civil rights movement in Ewing's community are mesmerizing. Stark shadows blot the street as white police officers advance on a small crowd of protesters and their beret-wearing leaders. A protester's upraised fist seems to stab out of the page. And Ewing captures the ugliness of a White Citizen's Council membership drive, the joy of civil rights rallies organized by the United Front of Cairo, burned crosses and shops, bullet holes in living room walls and armed police surrounding the Pyramid Court public housing project. He was on the scene in 1970 when a small group of American Nazis marched alongside a group of blacks who were picketing in Cairo's business district. The pickets' signs read, "No Justice. No Money." The Nazis' signs display swastikas and read, "White Youth Unite"and "Save Cairo." And he records Julian Bond's visit to Cairo.

The pictures have been interwoven with quotes from local activists, some of whom are seen in the photographs.

More than a quarter century after the fact, no one featured in Let My People Go looks at Cairo with anything more than guarded optimism. Yet the book is a testament to a passion for and belief in the ultimate power of justice.

Such depth of feeling seems as old-fashioned as the manual typewriters, automobile tailfins and striped, bell-bottom trousers that jar the eye in Ewing's photos. Today, Cairo boasts a jewel-like public library, antebellum mansions and some of the worst unemployment, teen pregnancy and welfare rates in the state. The town's population is half what it was in 1960.

Let My People Go is only one chapter in Cairo's unfinished story.

Gary Hart, a free-lance writer, lives in Murphysboro.

30 / February 1997 Illinois Issues

This photograph was taken on Commercial Street in March 1970. Begin left: Chief

Roy Burke, Randy Robinson, Ezell Littelton, Herman Whitfield, Cordell McGoy.

The photograph of Cairo police officers was taken on Washington Avenue at 7th Street in June 1969.

Illinois Issues February 1997 / 31

|

|