Illustration by Mike Cramer |

USED TO BE |

Illustration by Mike Cramer |

USED TO BE |

FAIR TIME

They're a link to our agrarian past

by Ann Londrigan

Crops are head-high and the heat's oppressive. It's fair time in Illinois.

Shrouded in nostalgia and ripe with sensation, fairs are enduring holdovers from the archives of Americana. A link to our agrarian past. A way for farmers to celebrate the traditions of their ancestors and an opportunity for city types to commingle with the animals and products of a simpler time.

And, well, at long last we can people- watch unchecked and feast on soybean- greasy corn dogs and sugar-drenched funnel cakes and drink lemon shake- ups 'til the cows come home.

Fairs are spectacles of historic proportions. Biblical even. Throughout recorded history, they have spread culture and promoted progress. It says in the book of Ezekiel (circa 500 B.C.):

"Tarshish was thy merchant by reason of the multitude of all kinds of riches; with silver, iron, tin and lead, they traded in thy fairs."

Some time way back when, before good roads, an unnamed entrepreneur discovered that if he lugged his goods to a nearby town on a busy day, he could turn a tidy profit. These ware- selling fairs capitalized on religious festivals, which brought many people to a city on a given day. Churches profited, too, from a new venue for spreading the word, not to mention rental fees for the use of their space.

The Latin word is "feriae," meaning holy day or holiday. In the Middle East, fairs were held in Mecca during the pilgrimage season. Romulus and other Roman leaders held fairs to attract people to Rome whenever laws were proclaimed.

The American agricultural fair was born under an elm tree in Pittsfield, Mass., where, in 1807, New England patriot and farmer Elkanah Watson exhibited a flock of sheep. Watson, considered the "father" of such fairs, wanted to show that the fleece on his sheep was as good as or better than wool imported from England.

Now a leading agricultural fair in the nation, the Illinois State Fair was designed on a similar premise 146 years ago. Members of the newly incorporated Illinois State Agricultural Society determined that a fair would jump-start farmers into improving the ag business by exposing them to the best methods and equipment. According to Patricia Henry, the fair's "unofficial historian," minutes from the meeting read:

"Homebred farmers were ignorant and bigoted because they read little and traveled even less."

Springfield won the bid for the first site and the four-day event began on Tuesday, October 11, 1853. For 25 cents admission, fairgoers could see the best products offered by the family farm: prize-winning stallions, mares, cattle, sheep, swine and poultry; the best ox yoke, chum, pump and portable grist mill; the best wine and field crops, including Illinois-grown hemp and tobacco; garden produce, flowers, needlework and kitchen goods.

In all, 765 entries earned $1, 500 in premiums, with the fair realizing a profit of $853.

That first year, five major rail lines into the capital city offered fairgoers such deals as half-price fares and free freight for all livestock and display materials. The next year featured three-hour speeches by Illinois' U.S. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, and then- Springfield lawyer Abraham Lincoln.

In time, permanent buildings and areas were added, including the Tented City, a camping area with police protection, a directory of inhabitants, telegraph and postal service. Special events became popular, too. At the

34 / July/August 1999 Illinois Issues

"Better Babies Conference," judges rated children between the ages of six months and 5 years on their health, looks and ability to crawl very fast. And the State Fair School of Domestic Science was designed for young women who wanted to "increase home efficiency."

In her ongoing research comparing fairs and theme parks, Carla Corbin, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, discovered that the agricultural fair was a site where prior to World War II rural people went to have a more urban experience, a crowded, complex environment. Later, as American society changed from a rural to an urban and suburban popu- lation, this purpose shifted. Urban dwellers, generations removed from a family farm, attended the fair to learn about that life.

The fair's role in agricultural technol- ogy and immediate sales is long gone. Modern progress in the form of grocery stores and produce brokers has left vegetable and fruit displays to hobbyists. Since the 1970s, machinery shows have dwindled at the fair, and major agricultural equipment by the big-name dealers, such as John Deere and Ford New Holland, has been replaced by riding mowers and small tractors for suburban "lawn farmers."

These days, attendance at the Illinois State Fair is about 30 percent agricul- tural and 70 percent urban. The grand- stand lineup gets the limelight and shares credit for the crowds with the carnival midway, free entertainment and concessions.

Raised in a family of carnival workers, Corbin's resume includes "four-legged girl" and "headless woman." (All crude illusions using mirrors, she confesses.) She notes that these surreal amusements, too, are long gone. Side shows, freaks and strip shows disappeared from the scene in the late '60s when it became improper to stare at people who were different and scantily clad women could be seen on television.

You can't take the farm out of the fair, however. With 80 percent of the land under cultivation in Illinois, agriculture is inextricably linked to the state fair and its smaller cousins, the 105 county fairs. A grand champion steer can be showcased for a premium of $1, 200. A prize-winning draft horse, while no longer useful in the scheme of farm life, can gamer $17, 000 on the fair circuit.

Last year's introduction of "barn tours" to the fair was an attempt to rekindle this urban-yearn for at least a look at rural life.

As David Foster Wallace writes in his 1994 travelogue on the Illinois State Fair, there's something sacred for the Midwesterner in the spectacle of the fair. The landscape is so vast, so silent, we have "the urge physically to com- mune, melt, become part of a crowd."

At last its time once again to people-watch with abandon, and eat corn dogs and funnel cakes. At least 'til the cows come home.

Ann Londrigan works for the Illinois Association of Park Districts. Her last piece for Illinois Issues was on the state's wineries.

35 / July/August 1999 Illinois Issues

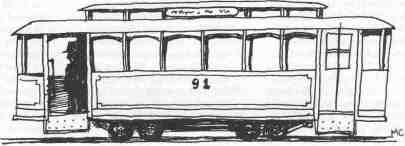

Illustration by Mike Cramer from a photograph in the Sangamon Valley Collection of Lincoln Library, Springfield |

MEMORY TRAIN |

Imagine, if you will, a frosty morning in February of 1944. World War II is raging in Italy and the South Pacific. But in Decatur, wives, mothers and sweethearts, the local equivalents of Rosie the Riveter, are waiting outside the Transfer House for the Interurban. White clouds of vapor mark their breathing while they stamp around in ice and snow. Suddenly, a silent train appears, almost like a dream. They climb aboard in their heavy boots and coats, falling asleep on the cushioned seats, waking a half hour later in Illiopolis, where they report for work in the sprawling munitions

Illinois Issues July/August 1999 / 35

complex owned by the Houdaille- Hershey Co.

The long gray sheds, where these women manufactured bullets and polished shell casings, still hug the prairie. The ghostly buildings stand empty in the middle of the corn- fields, easily visible to the passing motorists on 1-72. In fact, the inter- state is a kind of topographical clone of the old Interurban, an electrically powered rail system that, in its hey- day (1901-1955), hauled hundreds of thousands of passengers and millions of tons of freight along 550 miles of track. A short spur of those tracks is still visible near Illiopolis, used today by the Norfolk Southern Railroad, and the old Interurban right of way is clearly present all the way to Riverton, where one might dine today in the Interurban Restaurant, with its photos of old Interurban cars hanging proudly on the walls. The Interurban tracks once threaded through the city of Springfield, thence down to Chatham, roughly following Route 4. Today, Duane Carrell and other members of the Chatham Local Chapter of the National Railway Historic Society have repainted and refurbished the old Chicago and Alton Railroad Depot, turning it into a train museum, including Interurban artifacts, as well as other timetables, caps, uniforms, lanterns, switch keys, menus and bells. In like manner, Dale Jenkins of the Illinois Traction Society of Decatur continues to amass Interurban memorabilia and even publishes an Interurban newsletter.

So, in a way, the old Interurban lives on. Its abandoned sidings, spurs, and tracking, with their rotting crossties and gravel beds (known as ballast), appear (from the air) as a kind of stitchery, rough seams holding together the patch- work of the prairie, and the deeper patchwork of memories. If Lincoln and the farm culture provided an essential bonding for the region, then so did the Interurban, bringing together relatives and friends, especially on ritual occasions like Christmastime, weddings and family reunions. Little girls in their First Communion dresses sat proudly on the seats that were trimmed in wicker and leather. In the Parlor Car, a shy couple in midcourtship enjoyed a steak dinner, followed by a slice of pie ("liberal cut with cheese") and a cup of coffee, all for $1.75 at 1947 prices. An ordinary day was circled forever on the mental calendar, as if endowed with an aura or halo.

For many rural families in central Illinois, the Interurban was the closest thing to luxury in lives that were often drab or workaday, especially during the Depression years. Elegance could be purchased with a ticket that usually cost less than a dollar. Into a world often covered with ice or snow or dust, the Interurban intruded, bringing air-conditioned comfort and hot meals served on clean, starched tablecloths. The Interurban provided reliable transportation and a much- needed sense of grace and style in a world where everything was part of the old agricultural cycle. Moving at a leisurely pace (about 35 miles per hour), the Interurban enhanced the simplest of journeys, like a short hop from Clinton to Decatur, perhaps to see the dentist, flip through the latest magazines or take in the new Gene Autry movie.

One always arrived in style. The trains bore proud names like the City of Decatur, the Corn Belt Limited, the Indiana and the Capitol Limited. Some were painted bright orange (the Tangerine Flyer), and the special sleeping-car train was known appropriately as The Owl. Billed as "The People's Popular Railway," the Interurban was marketed as a clear alternative to coal-fired locomotives: "No dust, no dirt, no smoke, no cinders." Until 1930, the "parlor" (dining) cars boasted arched, stained-glass windows and gold leaf scrolling: "The most elaborate cars ever constructed for regular service on an electric railway," according to the owners.

Electric railways were extremely popular in the interval between the two world wars, but by the 1950s superhighways and faster cars began to put them out of business. The local Interurban, the third largest in the country, was the brainchild of U. S. Congressman William B. McKinley of Champaign. He was the founder and original owner of the Interurban line, which began in Danville. McKinley also underwrote the McKinley Foundation of the University of Illinois and the McKinley Bridge over the Mississippi River at St. Louis, which carried the Interurban tracks into the St. Louis terminal. Officially, the Interurban was first known as the Illinois Traction System (ITS) until 1937 when it became the Illinois Terminal Line (ITL). Although regular passenger service ceased in 1955, the Interurban still hauled freight well into the 1970s.

The passenger side of the business was remarkably safe and efficient. In wintertime, the lead car was equipped with a kind of cow-catcher or plowing device that swept aside snow and ice. Almost every community in central Illinois, and even farmsteads along the track, could depend upon hourly service, a standard that most airlines and today's Amtrak could hardly equal. People set their watches, and their lives, by that train. It even became part of the folklore of central Illinois, engendering this humorous if politically incorrect adage: "Never run after an Interurban or a woman, as another will be along any minute." But some of us will continue to run after the Interurban, at least in imagination, hoping perhaps, to slip between fresh sheets at a stop outside Peoria, sleep comfortably and awaken to a breakfast in St. Louis. The zoo beckons, and the world is still full of splendor, all waiting to be explored. All aboard!

Dan Guillory, an English professor at Millikin University in Decatur, is the author of Living with Lincoln: Life and Art in the Heartland, The Alligator Inventions and When the Waters Recede.

36 / July/August 1999 Illinois Issues

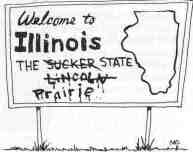

Illustration by Mike Cramer |

WHAT'S IN A NAME? Finding meaning in the mystery of state slogans by Lester Graham |

In 1955, some marketing geniuses in the Illinois legislature adopted "Land of Lincoln" as the state slogan. That moniker, with its straight- forward political intent, has been plastered on license plates and tourism brochures ever since. There's an older nickname, too. The 1914 edition of Dodd, Mead & Co.'s The New International Encyclopedia identifies Illinois as the "Prairie State," a pleasant sounding sobriquet also still in use, though there's little of the tall grass left.

Yet before the market-savvy "Land of Lincoln" or the genteel "Prairie State," many Illinoisans, with a wink, called their home the "Sucker State." Ask natives over the age of 60, and they'll probably grin and recall it with a sheepish, "Oh, yes."

Yet a thorough search of the biennial Illinois Blue Book won't uncover the term "sucker" among the official state symbols. Most recent scholarship has overlooked it as well. And even Robert P. Howard's more journalistic account of Illinois' past makes only a passing reference to it. Still, as recently as the 1970s, a weekly newspaper in the east central Illinois town of Mahomet was published under a banner that read "The Sucker State," perhaps the last vestige of that long-used nickname.

Its origins are uncertain. Amateur historians and pundits argued about it for more than 150 years. The most repeated and most believable explanation is in Gov. Thomas Ford's 1854 history of the state. Ford's research is expanded upon in Alexander Davidson's and Bernard Stuve's Complete History of Illinois from 1673 to 1873. Those authors cite one George Brunk of Sangamon County, who claimed to have been an eyewitness at the creation.

In the 1820s, Brunk recalled, the northwestern region of Illinois was important for its lead. Miners arrived each spring and left before the harsh winters. "Late in the fall of 1826, 1 was standing on the levee of what is now Galena, watching a number of our Illinois boys go on board of a steamboat bound down the river, when a man from Missouri stepped up and asked — 'Boys, where are you going?' The answer was, 'Home.' 'Well,' he replied, 'you put me in mind of suckers (a fish); up in the spring, spawn, and all return in the fall.'"

Gov. Ford's history offers another origin for the nickname, this one farther south and more grounded in the state's agricultural past. "The tobacco plant," Ford writes, "has many sprouts from the roots and main stem, which if not stripped off, suck up its nutriment and destroy the staple. These sprouts are called 'suckers,' and are thrown away, as is the tobacco worm itself."

Then Ford, using metaphor, and perhaps political spin, gets at what he sees as the truer meaning of the term. He compares tobacco 'suckers' to the southerners who settled the bottom tip of the state. "These poor emigrants from the slave States were jeeringly and derisively called 'suckers,' because they were asserted to be a burthen upon the people of wealth; and when they removed to Illinois, they were supposed to have stripped themselves off from the parent stem, and gone away to perish like the 'sucker' of the tobacco plant."

Half a century later, one southern Illinois historian compiled a haughty comeback. "It is well known," J.H.G. Brinkerhoff wrote with certitude in his history of Marion County, "that in the late summer and early fall, southern and middle Illinois is subject to extreme drought, often so long continued that water is not to be found for long distances across the prairies, except as obtained by the arts of man."

The "arts of man," Brinkerhoff explained, include sticking cane straws into mud chimneys made by crayfish, which have an "unerring instinct" for locating water. Thus, early travelers and surveying parties were called Suckers, and, by extension, "the whole people of the state."

Stephen A. Douglas, meanwhile, was said to have ascribed a similar art to the early French settlers, who, he said, were fond of sitting on verandas and "sucking juleps through straws." Davidson's and Stuve's history adds this note: "It is not improbable that a glass of the animating beverage (mint julep) served to quicken the memory of the honorable senator on the occasion."

It's this mystery, this richness of meaning in the oldest of Illinois' nicknames that renders it so unsuitable to modern promoters. "The Sucker State" is unlikely to appear on license plates anytime soon.

Lester Graham lives in Jerseyville and is a reporter for the Great Lakes Radio Consortium.

Illinois Issues July/August 1999 / 37