Marking history and community

By Tom league

Last August I spent four days in Texas with an old friend. Together we drove more than 1,200 miles—from the northern panhandle to the Rio Grande and back. During that time I believe I saw more than 120 historical markers. Virtually every town we passed through had at least one. On a small roadside turn-off in ranch country, there were actually four markers in a row. Collectively, these placards commemorated virtually all phases of the Lone Star state's history—from Indian battles to exploratory expeditions to oil wells, mines and other notable businesses. With generous support from government agencies, Texas may well have more historical markers per capita than any other state.

Back in Illinois a week later, I drove to Lincoln to help dedicate a marker to author William Maxwell. Comparisons between our markers program and the Texas markers inevitably came to mind. As an independently funded program, Illinois markers cannot match the sheer numbers that Texas has. But as I waited my turn to speak, it finally came to me. Just a block away from the Maxwell home, a marker honors Langston Hughes, the African-American poet who spent part of his childhood in Lincoln. Barely a block away in the opposite direction, another marker remembers the Niebuhr family of theologians. Downtown, a plaque notes the day that Abraham Lincoln christened the young city. We might not have the numbers in Illinois, but it would be hard for any state to match the diversity that our markers have in this city alone.

Most importantly, each Illinois marker has a community behind it. This includes the people who came up with the idea for it, the people who researched its subject, the people who raised the money to erect it, and the people who gathered to celebrate itsdedication. After all that work, a sense of ownership naturally arises. So Texas may have the numbers, but in Illinois our marker communities are unmatched. Below is a summary of the sites that such communities helped commemorate this year alone.

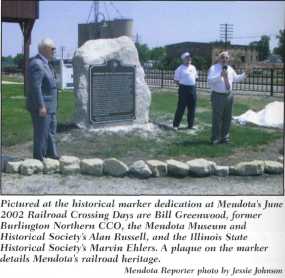

Railroads and the Founding of Mendota

This marker and its community record how important the railroad was to early Illinois. Mendota is an Indian word said to mean "crossing of the trails." The Chicago & Aurora Railroad planned to expand southwest from Aurora to meet the Illinois Central Railroad (IC). Meanwhile, the IC was building northward up the middle of the state. Its charter called for its main line to proceed northward from Cairo to the western end of the Illinois & Michigan Canal at LaSalle. From there it was to turn northwest toward the Galena mining district. During a chance meeting of several railroad officers in early 1852 in Boston, the lines agreed to have the C&A and the Central Military Tract Railroad meet the Illinois Central at the point closest to Aurora. Thus the curve of the IC toward Galena was moved to a point just north of where this marker was erected. In 1856 the C&A and the Central Military Tract Railroads merged and became the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad. That line, through recent mergers, has become the Burlington Northern Santa Fe. The Illinois Central, meanwhile, abandoned its line through Mendota in 1985.

The primary local sponsor for this marker was the Mendota Museum and Historical Society. Alan Russell conducted much of the research and arranged for the marker to be placed on a large block of native granite.

The William Maxwell Home, Lincoln

William Maxwell (1908-2000), author and editor, lived in a large, stately house in Lincoln from 1910 to 1920. He often returned to this home and Lincoln in his novels and short stories. His Midwestern childhood, particularly the loss of his mother in the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, influenced much of his

10| Illinois Heritage

writing. Maxwell graduated from the University of Illinois and then served as fiction editor for the New Yorker from 1936-1976. I le wrote 14 works of fiction and memoir, earning the American Book Award in 1980. His name is etched on the frieze of the Illinois State Library.

This marker's primary local sponsor was an ad hoc group called Friends of William Maxwell. Its leader was David Welch.

The Edwards Trace, Springfield

This was an important highway that predates even the arrival of European explorers. Called the Edwards Trace, an early word for trail, it reaches back to when herds of bison and other large mammals migrated along its path. Native Americans utilized the trail for seasonal migrations, trading, hunting and waging war. In the early 18 " Century, French trappers and priests began traveling along its path as it offered an alternative route to the waterways.

During the War of 1812, Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards, who later became the state's third governor, led a contingent of 350 rangers along the trail to Peoria for action against the Kickapoo Indians. From Kaskaskia and Fort de Chartres in the south, the trail led to Fort Russell near Edwardsville. It then passed by the current Lake Springfield on its way to Fort Clark near Peoria.

For early Illinois inhabitants, the Edwards Trace was the main overland route between southern Illinois and points north. Along its course came many of the pioneers who settled the Sangamon Valley. After Illinois attained statehood in 1818, this road carried heavy traffic and a wide variety of goods and commodities from north to south. As a result, a sunken path developed, a remnant of which can still be seen.

This marker's sponsors included the City of Springfield, the Sangamon County Historical Society and Walgreens Drugs. David Brady, manager of the Prairie Archives bookstore in Springfield, conducted the primary research.

Illinois Soldiers' And Sailors' Children's School, Normal

The Illinois Soldiers' and Sailors' Children's School (ISSCS) was established in 1865 in Normal as the Illinois Soldiers' Orphans' Home. On these grounds for 114 years scores of caregivers and educators provided thousands of children with a homelike environment. Dedicated in 1869, ISSCS provided a home for children of Civil War veterans who had been killed or wounded. In 1899, the state allowed the school to admit indigent children, especially those of veterans. Between 1907 and 1925, indigent children of non-veterans were admitted. In 1931, the name was changed to ISSCS. The facility closed in 1979 as the state began to favor foster family care for children instead of residential facility care. Most of it now serves as a community center for the city of Normal.

This marker's local sponsors included the Historic Preservation Commission of Normal and the ISSCS Historical Preservation Society, an alumni group. Yvonne Borklund was their coordinator. In addition, the Walgreens Drug Company provided a generous amount of support and sent a representative to the dedication ceremonies. The Society hopes that Walgreens' support of the markers will become a longterm partnership.

Illinois Heritage | 11