|

R a d i c a l f e m i n i s m i n 1 8 9 7

Jane Addams opens window of reform for Danville women's social club

By Janet Duitsman Cornelius

Mary Elizabeth Forbes was a private and prosperous daughter of a Danville pioneer family. In 1897 she was recently widowed, with two teen-aged daughters, and had inherited the management of ten farms and some city real estate.

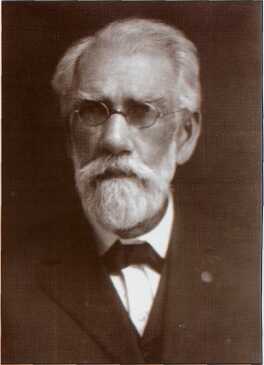

Jane Addams in her later years.

Photo courtesy the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library

|

She was soon to marry one of the most prominent men in Danville, Joseph English, founder of the city's First National Bank.

Forbes used a daily diary to express her loneliness and grief at the loss of her husband; she was a very private woman at a time when many Danville women were going out of their homes to organize mission societies, orphanages, and literary clubs. Forbes chose instead to focus on her two daughters, manage her property, and quietly support her church, in the tradition of a True Woman for whom "her home was her world." However, even Mary Forbes was enticed out of her home to a public lecture on Thursday night, November 4, 1897. According to her diary, she went with a friend to the Presbyterian church whom had to stand at the back of the church's lecture hall.

Addams had traveled from her Hull House residence in Chicago to speak in Danville for a purpose. Her appearance was sponsored by the Philanthropic section of Danville's newly organized Woman's Club, to hear "Jane Addams of Hull House fame," joining what a news reporter described as a "large audience of Danville's best people," some of whose members hoped to capitalize on Addams' fame to "arouse interest in their deserving work," according to a sympathetic newspaper editor. Addams, in turn, must have determined that a small city in east central Illinois was a promising arena in which to publicize her evolving theory that Americans had obligations to one another as a necessary requirement of living in a democratic society. Her address was titled "The Social Responsibilities of Citizenship."

Though Addams and Ellen Starr had established Hull House as a settlement center only eight years before her trip to Danville, Addams was already very well known to a downstate area which looked to Chicago for its political and cultural inspiration. William Jewell, the editor of the Danville Daily News described her as "one of the world's greatest charity workers," one who had "made sacrifice of wealth, ease and social position, gone to the needy, lived and worked with them." By 1897, Hull House had grown from a decaying mansion in the heart of the immigrant 19th District to a center for some forty clubs, a day nursery gymnasium, dispensary, playground, and an art gallery. To operate this growing center, Addams had exhausted her own wealth and had become a fundraiser, making profitable connections with wealthy and supportive Chicago women. The remarkable

6 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

activists and scholars who had gravitated to Hull House increased its fame and value to the community. Hull House was a focal point for the settlement house movement in the United States and Addams was gaining a reputation as a sought-after lecturer and a writer of articles in the Atlantic, North American Review, and other periodicals.

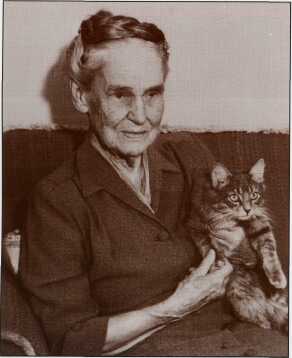

William R. Jewell, editor of the Danville Daily News in 1897, was a strong supporter of women's rights.

Photo courtesy Vermilion County Museum

|

A key group of Danville's elite women were strongly influenced by Addams' example and by the Chicago Woman's Club, one of the oldest and strongest of the Woman's Clubs in Illinois and a strong supporter of Hull House. This group of Danville women determined, in the words of one of their founders, educator Frances Pearson Meeks, to "try to organize one of those new-fangled women's clubs, much talked of." One reason was boosterism; after all, "was not Danville as up and coming as any town in the United States?" Peoria, Springfield, and many villages and towns had well-established women's clubs. Another reason was that a Danville club would be part of a state, even a national group, which would give its women influence beyond their own numbers.

Several Danville women had made pilgrimages to Hull House and to the 1893 World's Fair, and they were aware that hundreds of Chicago Woman's Club members had participated in congresses set up relief systems for women and families in the 1893 depression, and worked to establish kindergartens, visiting nurses, parks, clean streets, and pure foods. Attracted by the pragmatic approach to this vision of creating a more humane, clean, efficient, honest society, Danville women attended the first state meeting of the Illinois Federation of Women's Clubs in the clubhouse of the Peoria Woman's Club in October, 1895. The Danville women, organizing their club immediately after, chose as their motto "Not for Ourselves, but for Humanity." They recruited as members a mixture of the socially prominent, the socially active, including "every newcomer, every returned college graduate, [and] every girl or woman who had 'done things' at home or abroad," as Pearson Meeks later recollected. Eva Sherman, the noted principal of Danville's Washington school and club founder, recruited many teachers and scheduled meetings on Saturdays so they could attend.

As the first large, public women's organization in Danville, the Woman's Club had put itself in a position to "get things done" in the community. Leaders of the club's Philanthropy section in 1896 immediately focused on the needs of children in the public schools, which brought

|

As the first large,

public women's organization

in Danville, the Woman's Club

had put itself in a position

to "get things done" in the

community.

|

them into politics. The club claimed credit for the election of a "lady member on the school Board" and having a "Woman Truant Officer" appointed. The latter, club member Franc Slocum, helped identify over 400 children who didn't have enough clothes to attend

school, which must have been an eye-opener for the middle class clubwomen, who responded with both direct philanthropy and political action. They made and distributed clothes for the children so they could stay in school, but they also appointed club members to visit the schools regularly and to report to the school board on overcrowding. They also established Danville's first kindergarten.

It was at this point in their evolution that the Philanthropy section club members decided to invite Addams to lecture in Danville. They obtained use of the First Presbyterian Church's meeting hall and charged the audience 25 cents for the lecture, from which they paid Addams' expenses and used the

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 7

Frances Pearson Meeks, one of the founders of the Danville Woman's Club.

Photo courtesy of the Vermilion County Museum

|

profits to buy "clothing for destitute school children." No advertisements were purchased in the newspapers, but the club had the strong and influential support of Editor Jewell of the Danville Daily News. Jewell, whose wife Mary had helped establish the Woman's Club, was considered the spokesman of the Danville establishment by 1897, when he was serving his last year as editor of his moderately Republican newspaper. Jewell was a strong supporter of women's political rights; he had enthusiastically welcomed the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association's meeting in Danville in 1894, and had been labeled a "friend of woman's suffrage" by the journal of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In November, 1897, Jewell praised Addams effusively and urged a large attendance for her speech, promising that Addams would give the club members and the people of Danville "some practical information in the work of charity." Jewell was referring to Addams' practical work at Hull House and possibly also the publication of Hull House Maps and Papers in 1895, a collaborative study of social conditions in the 19th ward by Hull House professional women and men.

It seems, however, that Addams had her mind on theory as well as practicality when she appeared in Danville. Her first book, Democracy and Social Ethics, (1902), based on articles she was writing at the time of her speech in Danville, dealt with the need for the fortunate classes to recognize that in modern industrial society all were dependent on one another; the old code of personal morality was no longer practical because without the advancement and improvement of all, no one could hope for 'lasting improvement" in one's social and moral condition. Addams also warned in her writings that moral failing of "excessive self-regard" came from a "feeling of exceptionalism that results from limiting our circle of acquaintances to others who share our beliefs." She challenged her audiences to deliberately seek out those whose experiences were different from their own. Through learning to see the world through the eyes of others, Americans could transform "the

|

She challenged

her audiences to deliberately

seek out those whose experiences

were different from

their own.

|

democratic belief in the worth and dignity of all human beings into a social ethics."

The Danville Commercial gave the lecture perfunctory coverage, complimenting the large crowd but describing the oft-told story of Hull House as "the most interesting feature of the address." But Jewell in the Daily News perceived that Addams' address was more far-reaching. To illustrate her message of social obligations, she contrasted the rampant individualism of wealthy Americans with the noblesse oblige of the European upper classes and observed that "the American people hadn't gotten the theory [of social obligations] or didn't feel it as keenly as did the people in the older [industrial] countries." However, she then went beyond the noblesse oblige concept and undoubtedly told her audience how she herself, by learning to see the Hull House neighborhood

through the eyes of its residents, had transformed her own noblesse oblige perspective (giving them what they should have) to one of helping her neighbors with what they themselves needed and wanted. Jewell recognized, further, that Addams was framing her experience into a social theory; he concluded that she showed great evidence of thought and study as she

8 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

"insisted on a newer and almost radical social movement to elevate the social and moral life of the working classes."

Not surprisingly, her "refined and cultured" Danville audience, composed mostly of socially prominent women, resisted Addams' program of an "almost radical social movement," but her address was well received and "all felt well repaid for their attendance." A significant reason for her positive reception, in addition to her Hull House fame, was her distinctive and attractive persona, something frequently noted by those who came into contact with Jane Addams. The Daily News assessment reported especially her effectiveness as a speaker, noting that her "enunciation and pronunciation were faultless" and that "she used a charming way in demonstrating a point which completely won the hearts of the audience whether they coincided with her opinions or not."

After her appearance in Danville, Addams went on to demonstrate her "experiential social ethics" in a variety of courageous ways. Hull House became the headquarters for political work in the 19th district, the site of trade union meetings, and a platform for radical speakers. The members of Danville's Woman's Club, many of whom were wives of employers, did not encourage unions as part of their social program. However, the club members did adopt Addams' pragmatic methods for improving the lives of Danville's less fortunate and some of them, at least, ventured beyond their comfortable lives to involve themselves in the worlds of others. They established a longstanding Shoe and Stocking Fund for children in need and pestered the City Council into cleanliness programs, including garbage collection, waste paper drives, and a law against spitting on sidewalks.

They led in the fight against tuberculosis, set up impure milk and grocery store inspections, and established a Well Baby Clinic. They continued to look to Hull House; in 1910 Danville women sought Hull House assistance in establishing a Travelers' Aid society and hired a young woman trained at Hull House as its director. The Danville Woman's Club led its city's citizens into a greater realization of the "Social Obligations of Citizenship," though they did not carry these obligations as far as Addams would have liked for them to do.

Janet Duitsman Cornelius of Penfield is an adjunct faculty member at Eastern Illinois University, where she teaches courses in constitutional, southern, and women's history. She retired from teaching and administration at Danville Area Community College and is a former ISHS hoard member. She and Martha Kay are completing a manuscript on Danville women in the Progressive era.

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 9

|