|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Legend of Le Rocher

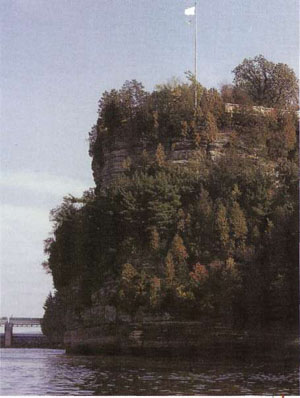

Nehemiah Matson's account of the massacre of Illinois Indians at Starved Rock has long been accepted as historical fact in the Prairie State. Based on oral histories dimmed by fading memories, the legend has persisted for more than two centuries. But is it true? That question will be put to the test at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the Illinois State Historical Society held this year in the Illinois River Valley April 28-29. Mark Walcynzski, a local historian and forensic investigator for the Illinois State Police, will deliver the banquet's keynote address, "The 1769 Massacre at Starved Rock: A Forensic Investigation of the Starved Rock Legend." To prepare members for what we know will be a fascinating program followed by a spirited discussion, we reprint Matson's original version of the "The Rock of Refuge," published in 1874 in his French and Indians of Illinois River. *For more information on the Society's Annual Meeting, or to attend the banquet on April 28, call 217-525-2781. Illinois Heritage 15

During a heavy rain storm and the darkness of night, the Illinoisans launched their canoes, crossed the river and ascended Starved Rock. Here on this rock were collected the remnants of the Illinois Indians, consisting of about twelve hundred, three hundred of whom were warriors. On this rock the fugitives considered themselves safe from their enemies, and the offered up prayers and sang songs of praise to the great Manito for their safe deliverance. Many years before, [Henri de]Tonti, with fifty French soldiers and one hundred Indian allies, held this rock when attacked by two thousand Iroquois, and put them to flight; consequently, on this spot they felt secure. Morning came, and with it a clear sky and a bright sun; and from their elevated position they look down on their enemies encamped on the great meadow below. Soon the allied forces were in motion, moving on the town for the purpose of completing their bloody work; but they soon discovered that their intended victims had fled. The town was burned and the slain left unburied, where their swollen and distorted remains were found some days afterwards. The allied forces forded the river on the rapids, surrounded Starved Rock, and prepared themselves for ascending it in order to complete their victory. With deafening yells the warriors crowded up the rock pathway, but on reaching the summit they were met by brave Illinoisans, who, with war-clubs and tomahawks, sent them bleeding and lifeless down the rugged precipice. Others ascended the rock to take part in the flight, but they, too met the fate of their comrades. Again and again the assailants rallied, and rushed forward to assist their friends, but one after another were slain on reaching its summit, and their lifeless bodies thrown from the rock into the river. On came fresh bands of assailants, who were made valiant by their late victory, and the fearful struggle continued until the rock was red and slippery with human gore. After losing many of their bravest warriors, the attacking forces abandoned the assault and retired from the bloody scene. The besiegers and besieged On a high, rock cliff south of Starved Rock, and known as Devil's Nose, the allied forces erected a ternporary fortification. During the night the collected small timbers and evergreen brush, with which they erected a breastwork. From this breastwork they fired on the besieged, killing some and wounding others, among the latter was Kineboo, the head chief of the tribe. The fortifications protecting the south part of Starved Rock, had fallen into decay, fifty-one years having elapsed since the Frerich abandoned Fort St. Louis. The palisades had rotted off, and the earthworks mouldered away to one-half their original hight (sic), consequently they afforded but little protection. To remedy the defect on this side of the old fortress, the besieged cut down some of the stunted cedars that crowded the summit of the rock, with which the erected barricades along the embankments to shield themselves from the arrows and rifle balls of the enemy. The besieged were now protected from the missiles of their assailants, but another enemy equally dreadedóthat of hunger and thirstóbegan to alarm them. When they took refuge here on the rock, they carried with them a quantity of provisions, but this supply was now exhausted and starvation stared them in the face. At first this rock was thought to be a haven of safety, but now it was likely to be their tomb, and without a murmur brave warriors made preparations to meet their fate. Day after day passed away, mornings and evenings came and went, and still the Illinoisans continued to be closely guarded by the enemy, leaving them no opportunity to escape from their rocky prison. Famishing with thirst caused them to cut up some of their buckskin 16 Illinois Heritage

clothing, out of which they made cords to draw water out of the river, but the besiegers had placed a guard at the base of the rock, and as soon as the vessel reached the water they would cut the cord, or by giving it a quick jerk the water drawer would be drawn over the precipice, and his body fall lifeless into the river. As days passed away, the besieged sat on the rock, gazing on the great meadow below, over which they had oftimes roamed at pleasure, and they sighed for freedom once more. The site of their town was in plain view, but instead of lodges and camping tents, with people passing to and fro, as in former days, it was now a lonely, dismal waste, blackened by fire and covered with the swollen and ghastly remains of the slain. Buzzards were hovering around, flying back and forth over the desolated town, and feasting on the dead bodies of their friends. At night they looked upon the silent stars toward the spirit land, and in their wild imagination saw angels waiting to receive them. While sleeping they dreamed of roaming over woods and prairie in pursuit of game, or cantering their ponies across the plains, but on awakening it was found all a delusion. Their sleep was disturbed by the moans and sighs of the suffering, and when morning came it was but the harbinger of another day of torture. From their rock prison they could see the ripe corn in their fields, and on the distant prairie a herd of buffalo were grazing, but while in sight of plenty they were famishing for food. Below them, at the base of the rock, flowed the river, and as its rippling waters glided softly by, it appeared in mockery to their burning thirst. They had been twelve days on the rock, closely guarded by the enemy, much of the time suffering from hunger and thirst. Their small stock of provisions was long since exhausted, and early and late the little ones were heard crying for food. The mother would hold her infant to her breast, but alas the fountain that supported life had dried up, and the little sufferer would turn its head away with a feeble cry. Young maidens, whose comely form, sparkling eyes and blooming cheeks were the pride of their tribe, became pale, feeble, and emaciated, and with a feeling of resignation they looked upward to their home in the spirit land. One of the squaws, the wife of a noted chief, while suffering in a fit of delirium caused by hunger and thirst, threw her infant from the summit of the rock into the river below, and with a wild, piercing scream, followed it. A few brave warriors attempted to escape from their prison, but on descending from the rock were slain by the vigilant guards. Others in their wild frenzy hurled their tomahawks at the fiends below, and singing their death song, laid down to die. The last lingering hope was now abandoned; hunger and thirst had done its dreadful work; the cries of the young and lamentation of the aged were heard only in a whisper; their tongues swollen and their lips crisped from thirst so that they could scarcely give utterance to their sufferings. Old white headed chiefs, feeble and emaciated, being reduced almost to skeletons, crept away under the branches of evergreens and breathed their last. Proud young warriors preferred to die upon this strange rocky fortress by starvantion and thirst, rather than surrender themselves to the scalping knives of a victorious enemy. Many had died; their remains were lying here and there on the rock, and the effluvium caused by the putrefaction greatly annoyed the besiegers. A few of the more hardy warriors feasted for a time on the dead, eating the flesh and drinking the blood of their comrades as soon as life was extinct. A party of the allied forces now ascended the rock and tomahawked all those who had survived the amine. They scalped old and young, and left the remains to decay on the rock, where their bones were seen many years afterward. Thus perished the large tribe of Illinois Indians, and with the exception of a solitary warrior, they became extinct. A ghastly spectacle A few days after the destruction of the Illinois Indians, a party of traders from Peoria, among whom were Robert Maillet and Felix Ta Pance, while on their return from Canada with three canoes loaded with goods, stopped at the scene of the late tragedy. As the approached Starved Rock, which at that time was called Le Rocher, they noticed a cloud of buzzards hovering over it, and at the same time they were greeted with a sickening odor. On landing from their canoes and ascending the rock, the found the steep, rocky pathway leading thereto stained with blood, and among the stunted cedars that grew on the cliff were lodged many human bodies, partly devoured by birds of prey. But on reaching the summit of Le Rocher, they were horrified to find it covered with dead bodies, all in an advanced state of decomposition. Here were aged chiefs, with silvered locks, lying by the side of young warriors, whose long raven black hair partly concealed their ghastly and distorted features. Here, too, were squaws and papooses, the aged grandmother and the young maiden, with here and there an infant, still clasped in its mother's arms. Illinois Heritage 17 Some had died from thirst and starvation, others by the tomahawk or war-club; of the latter a pool of clotted blood was seen at their side. All the dead, without regard to age or sex, had been scalped, and their remains, divesting of clothing, were lying here and there on the rock. These swollen and distorted remains were hideous to look upon, and the stench from them so offensive that the traders hastened down from the rock and continued on their way down the river. On reaching La Vantum, a short distance below Le Rocher, the traders met with a still greater surprise, and for a time were almost ready to believe what they saw was all delusion instead of reality. The great town of the west had disappeared; not a lodge, camping tent, nor one human being could be seen; all was desolate, silent and lonely. The ground where the town had stood was strewn with dead bodies, and a pack of hungry wolves were feeding upon their hideous repast. Five months before, these traders, while on their way to Canada, stopped at La Vantum for a number of days in order to trade with the Indians. At that time the inhabitants of the townóabout five thousand in numberówere in full enjoyment of life, but now their dead bodies lay mouldering on the ground, food for wolves and buzzards. Maillet and La Pance had bought of these people two canoe loads of furs and pelts, which were to be paid in goods on their return from Canada. The goods were now here to make payment, according to contract, but alas the creditors had all gone to their long home. The smell from hundreds of putrified and partly consumed remains, was so offensive that the traders remained only a short time, and with sadness they turned away from this scene of horror. Again, boarding their canoes they passed down the river to Peoria, conveying thither to their friends the sad tidings. Relics of the tragedy On the following spring, after the annihilation of the Illinoisans Indians, a party of traders from Cahokia, in canoes loaded with furs, visited Canada, making thither their annual trip in accordance with their former custom. On reaching Peoria they heard of the destruction of the Illinois Indians on Starved Rock, and were afraid to proceed further on their journey, not knowing but the victors were still in the country, and they, too, would meet a like fate. After remaining a few days at Peoria, they proceeded on their way, accompanied (as far as Starved Rock) by twenty armed Frenchmen and about thirty Indian (sic). With this escort was Father Jacques Buche, a Jesuit priest of Peoria, and some account of his observations are preserved in this manuscript. When the voyageurs arrived at La Vantum, they found the town site strewn with human bones. These, with a few charred poles, alone marked the location of the former great town of the west. Scattered over the prairie were hundreds of skulls. Some of these retained a portion of flesh and were partly covered with long black hair, giving to the remains a ghastly and sickening appearance. This party also ascended Le Rocher, and found its summit covered with bones and skulls. Among these were found knives, tomahawks, rings, beads and various trinkets, some of which the travelers carried with them to Canada, and now can be seen among the antiquarian collection at Quebec. Various accounts are given, both by French and Indians, of seeing in after years relics of this tragical affair on the summit of Starved Rock. Bulbona, a French Indian trader, who was known by many of the settlers, said when a small boy he accompanied his father in ascending Starved Rock, and there saw many relics of this fearful tragedy. This was only fifteen years after the massacre of the Illinois Indians, and the rock was covered with skulls and bones, all in a good state of preservation, but bleached white by rain and sun. On my first visit to Starved Rock, nearly forty years ago, I found a number of human teeth and small fragments of bones. Others have found relics of the past, such as beads, rings, knives, &c. About thirty-five years ago a human skull, partly decayed, was found at the root of a cedar tree, buried with leaves and dirt. A rusty tomahawk and a large scalping knife, with other articles, also human bones, were taken out of a pit hole, a few years ago. The early settlers have found many things on the summit of Starved Rock, and still retain them in their possession as relics of the past. 18 Illinois Heritage |

|

|