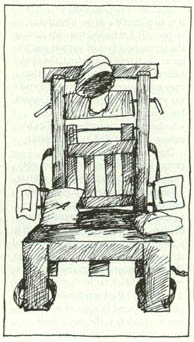

ty itsell, which is that our criminal justice professionals were too incompetent to do it well every time.) The electric chair, an improvement in its day, was eventually banned for the same reason. Decent people have trod this path before us; Calvin abhorred burning heretics alive in favor of the more merciful sword, and no doubt was scorned as a liberal because of it. Then, as now, these small steps toward mercy were taken not to spare the victims' agonies but the public's. Half-hearted as they seem to abolitionists, they reveal a people uneasy with the official taking of life, and eager to distinguish its barbarity from that of the executed. Opinion surveys are of little use in plumbing the public mind about such a vexing subject. Few people tell pollsters the truth (assuming they acknowledge it to themselves) about their darker feelings. Can we infer a motive from the fact that capital punishment's only certain result is to reduce the state's population of social outcasts, among them mental defectives, racial minorities, addicts and sociopaths? A good example is the now famous Anthony Porter. "Porter came within 48 hours of being executed for the basic reason that his IQ was 51," says Locke Bowman, legal director of the MacArthur Justice Center of the University of Chicago Law School, recalling why the Illinois Supreme Court granted a reprieve. "If you enhance his IQ by 50 points, he would now be a dead man, and that's not the way anybody, pro or con the death penalty, wants to run our criminal justice system," he is quoted as saying in the Chicago Sun- Times. No, people do not wish an innocent man of normal intelligence to be put to death without cause. But killing a retarded man - especially one prone to violent misbehavior, as Porter was - is the way quite a lot of people want to run our criminal justice system. Our Porters are our modern-day witches, fearsome and unsettling, the kind of people who have been the first to be sent to the stake in every society. Bill Ryan of the Illinois Moratorium Campaign, quoted in the Arlington Heights-based Daily Herald: "I think the idea that we're killing innocent people was just too much for people to bear." The public seems to be bearing it quite well, in fact. Perhaps that's because a cynical public assumes that while the recent Death Row escapees may have been not guilty of the crimes for which they were sentenced to death, they -most of them dangerous people with long records and bad habits - are anything but innocent. An incompetent criminal justice system fails to punish the guilty very dependably, and a lot of people reason that if those wrongly imprisoned didn't do the crimes for which they were condemned, they probably got away with others just as bad or worse. Albert Camus, among other thinkers, argued that imprisonment for life is cruel. Most apparently believe it not quite cruel enough. To allow the perpetrators of some crimes to live, even in the straitened circumstances of a jail cell, and thus to enjoy what their victims no longer can - life especially - strikes most people as wrong. To the familiar complaint that killing killers make us all killers, a decisive part of the public does not think that killing a murderer is murder, because the murderer, unlike the victim, is not innocent. The only way to prevent such an injustice is to put them to death. Of course, the value of human life - the murderer's, not the victim's- has gone up in the past century or so. In colonial days, people faced death by hanging if convicted of burglary, counterfeiting, piracy or rape, as well as murder or treason; not so long ago, Americans happily strung up horse thieves. In the modern era, punishment was limited to the taking of life, and most recently to the egregious taking of life. This trend marks social progress as much as moral progress; we are less fearful of social disorder, and so can dare to be merciful. But fear of moral disorder also plays a part in support for capital punishment. The United States remains a profoundly Puritan society. Building God's city on earth means doing His work here, including punishing sinners. This desire to punish is often traced to the urge for revenge, a low desire to inflict harm with no purpose other than to assuage one's own feelings of anger. Certainly, families of victims may wish revenge, as indeed do many in the community at large when a crime makes us feel momentarily like family (as happens when a child is murdered, for example). The rest of us seek something else, something more civic-minded - the restoration of moral order, or as H.L. Mencken put it, "the peace of mind that goes with the feeling that accounts are squared." Arguing against the death penalty on the reasonable grounds that it is ineffectual or uneconomic assumes that effectuality and economy are its purpose. In the end, most people support the death penalty not because they think it works but because they think it is right. Even if most people agree that it is but a gesture, they feel it is a gesture that must be made - our way of affirming that, in this place and time, there are limits, that conduct is not unbounded. Putting a murderer to death is a rhetorical gesture, aimed not at unnerving future criminals but at bolstering the rest of us. It's a dirty job, one might say, but everyone's got to do it. . James Krohe Jr is a contributing editor of lllinois Issues.

|

Pages:|1 ||2 | |3 ||4 | |5 ||6 | |7 ||8 | |9 ||10 | Pages:|11 ||12 | |13 ||14 | |15 ||16 | |17 ||18 | |19 ||20 |

Pages:|21 ||22 | |23 ||24 | |25 ||26 | |27 ||28 | |29 ||30 | Pages:|31 ||32 | |33 ||34 | |35 ||36 | |37 ||38 | |39 ||40 | Pages:|41 ||42 | |43 ||44 |