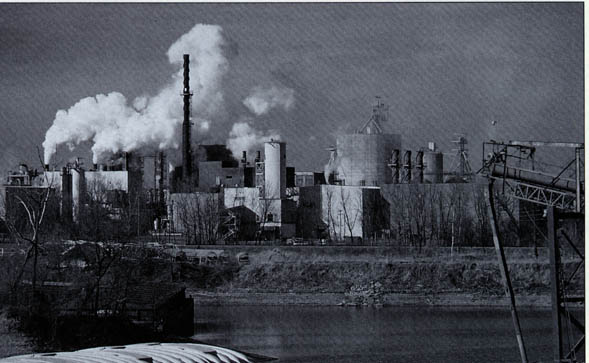

In one year, industries "legally released more than 100 million pounds of toxic chemicals into the environment. "

nerve gas - to kill people. DDT did not have enough deleterious effects on the human nervous system (at least immediately) to qualify for spraying on the enemy But it sure killed bugs. Most of them, anyway The survivors came back stronger than ever, as sure a confirmation of Darwin's theory of natural selection as we are ever going to find. Agricultural chemicals are the weak sisters of nerve gasses. Their development resulted from the search for weapons; it was with a warlike mentality that we first deployed them. Minor agricultural pests suddenly became fearsome public enemies; harmless and often pretty little weeds became the bane of roadside ditches. We declared war on flowers. To our everlasting shame, we won. We convince ourselves that this chemical warfare kills only weeds and bugs, only certain kinds of weeds and bugs, and those weeds and bugs alone. Is chemistry really that selective? Only if we maintain the utter fantasy that we are biologically different from other life forms can we believe that these chemicals will not in some way affect us. Acknowledging reality recognizing the enmeshed and central place of humanity in the web of all life, we have every reason to be concerned. Living Downstream draws special attention to the unintended consequences of our warfare mentality In war; immediate and demonstrable results are all that matters; kill the proclaimed enemy first, assess the damages to ourselves afterward. Rushing chemicals from the laboratories to the fields, we made household names of substances now regarded as dangerous. Benzene, once a common additive in gasoline, cleaning products and pesticides, is now recognized as a cause of leukemia and a possible source of myeloma. And it is everywhere: in lakes, ponds, reservoirs, underground rivers, a "ubiquitous pollutant," writes Steingraber. Thirty years ago, no one saw benzene as harmful, so everyone armed themselves with the stuff. Even when we do recognize the possible dangers of one chemical or another, we do not take the necessary steps to remove them from our environment. The national government and several states maintain lists of known and suspected carcinogens, lists that are appallingly long. But that is all they do. Known carcinogens are not outlawed; we allow anyone and everyone to breathe and imbibe them every day Every now and again the public gets in an uproar over some chemical or another; a few years ago it was alar and apples, in more recent years atrazine levels in drinking water. Little do we realize that this is merely the tip of the iceberg. Tests for toxicity are of course made individually How much atrazine before a rat gets to feeling puny? Our real life exposures are not limited, however, to any one chemical. Following Steingraber's careful argument, we realize that we are, over our long life spans, exposed to dozens of chemicals in bewildering combinations. The effect of each may be negligible in itself, but the cumulative effect of all is far more likely to be devastating. It is also, scientifically speaking, virtually impossible to determine. When experts say that there is no scientific evidence that such and such a substance causes cancer, they are speaking the literal truth. But this is only because science has not found an acceptably controlled experiment that can test the hypothesis. Lack of scientific proof that something is harmful does not imply its opposite, that the stuff is harmless. It means only that it is not

|

Pages:|1 ||2 | |3 ||4 | |5 ||6 | |7 ||8 | |9 ||10 | Pages:|11 ||12 | |13 ||14 | |15 ||16 | |17 ||18 | |19 ||20 |

Pages:|21 ||22 | |23 ||24 | |25 ||26 | |27 ||28 | |29 ||30 | Pages:|31 ||32 | |33 ||34 | |35 ||36 | |37 ||38 | |39 ||40 | Pages:|41 ||42 | |43 ||44 |